Tuberculosis

What is tuberculosis (TB)?

Tuberculosis (TB) is a deadly infectious disease. Every year, over 10 million people develop active TB and around 1.3 million die from it.

TB is often thought of as a disease of the past but a recent resurgence and the spread of drug-resistant forms make it very much an issue of the present day.

Almost half a million people develop multidrug-resistant strains of the disease every year. More people die of tuberculosis every year than from HIV/AIDS.

Though the global death rate from TB dropped more than 40 percent in the years between 1990 and 2011, there are still crucial gaps in coverage and severe shortcomings when it comes to diagnostics and care options.

MSF and tuberculosis

MSF has been fighting TB for decades. We provide treatment for the disease in many different contexts, from remote communities in South Sudan, to vulnerable patients in places like Uzbekistan.

In 2023, MSF started 25,377 people on TB treatment.

Tuberculosis: Key facts

1,300,000

TB DEATHS IN 2022

17,800

PEOPLE STARTED ON FIRST-LINE TREATMENT FOR TB BY MSF IN 2022

2,695

PEOPLE STARTED ON MULTI DRUG-RESISTANT TB TREATMENT IN 2023

What is drug-resistant tuberculosis (DR-TB)?

Drug-resistant and multidrug-resistant tuberculosis (DR-TB and MDR-TB) are variants of the disease that do not respond to the customary first-line drugs. These remain a public health crisis.

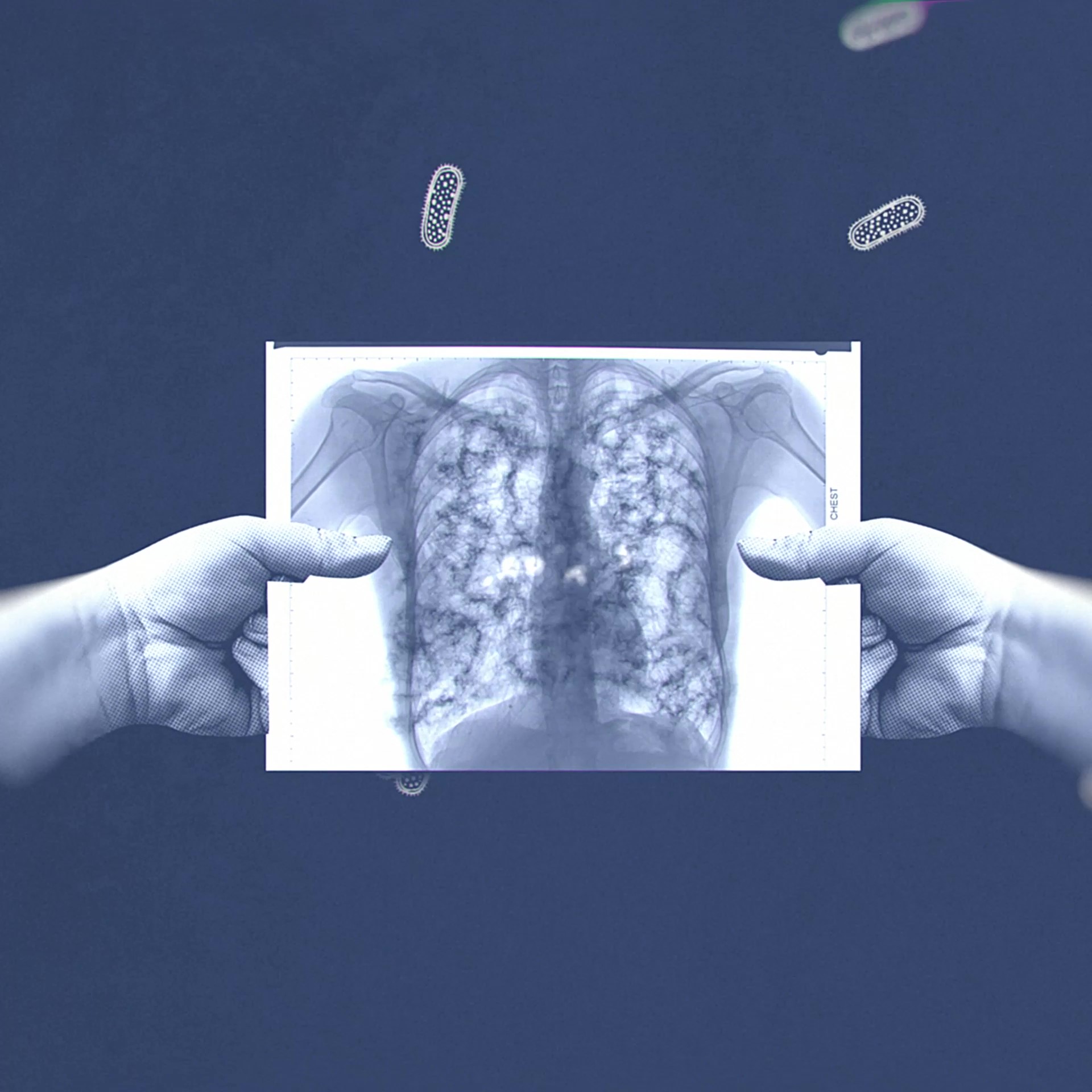

What causes TB?

TB caused by a bacterium (Mycobacterium tuberculosis) that is spread through the air when infected people cough or sneeze.

The disease most often affects the lungs but it can infect any part of the body, including the bones and the nervous system.

Most people who are exposed to TB never develop symptoms, since the bacteria can live in an inactive form in the body, but if the immune system weakens, such as in malnourished people, people with HIV or the elderly, TB bacteria can become active.

Five to 10 percent of people infected with TB will develop active TB and become contagious at some point in their lives.

What are the symptoms of TB?

Symptoms include a persistent cough, fever, weight loss, chest pain and breathlessness in the lead up to death. TB incidence is much higher and is a leading cause of death among people with HIV.

How is TB diagnosed?

The research and development (R&D) of new, more effective diagnostic tools and drugs for TB have been severely lacking for decades.

In countries where the disease is most prevalent, diagnosis has depended largely on one archaic test for the last 120 years – smear microscopy, the microscopic examination of sputum, or lung fluid, for the TB bacilli.

The test is only accurate half of the time, even less so for patients who also have HIV.

This means that too many patients start treatment late – if they start it at all.

Children, who often cannot produce sputum, urgently need a new diagnostic tool, especially since they are particularly vulnerable to dying if they develop active TB.

A new diagnostic test, Xpert MTB/RIF, was introduced in 2010 and MSF has used it in many of its programmes since. It’s not applicable to all settings, nor is it effective for diagnosing children or patients with TB that occurs outside of the lungs (extra-pulmonary TB), so MSF continues to call for further R&D in diagnostics for TB.

How is TB treated?

TB is a treatable and curable disease. A course of treatment for uncomplicated TB takes a minimum of six months.

According to the WHO, an estimated 74 million lives were saved through TB diagnosis and treatment between 2000 and 2021.

When patients are resistant to the two most powerful first-line antibiotics (rifampicin and isoniazid), they are considered to have multidrug-resistant (MDR) TB.

MDR-TB is not impossible to treat, but the drug regime is arduous, taking up to two years and causing many side-effects.

Extensively drug-resistant (XDR) TB is identified when resistance to second-line drugs develops on top of MDR-TB. The treatments for XDR-TB are limited.

In many places where we work, supervising all TB patients during their treatment is difficult to impossible. To help patients complete their treatment, MSF has introduced more flexible strategies.

One of these is TB PRACTECAL, a cutting-edge phase II/III clinical research project to find short, tolerable and effective treatments for people with DR-TB.

Seizing upon the opportunity of the first new TB drugs in half a century, MSF has partnered with the London School of Hygiene and Tropical Medicine and other global leaders in medical research, as well as ministries of health in affected countries, to take action.

Together, they share one big goal: to save the lives of hundreds of thousands of people with DR-TB and close the deadly treatment gap that is fuelling the global crisis.

Where does TB occur?

TB occurs in every part of the world, however the vast majority of cases and deaths are in low- and middle-income countries. According to the World Health Organization, in 2022, around two-thirds of all TB cases occurred in just eight countries: Bangladesh, China, Democratic Republic of the Congo, India, Indonesia, Nigeria, Pakistan and the Philippines.

Listen to British doctor Emily Wise discuss her time treating TB in Uzbekistan on the MSF podcast, Everyday Emergency

TB: News and stories