Crisis in Sudan

On Saturday 15 April 2023, a brutal civil war broke out across Sudan with a wave of gunfire, shelling and airstrikes.

The violence between the Sudanese Armed Forces (SAF) and the Rapid Support Forces (RSF) has trapped millions of people in the middle of an unexpected conflict. Hundreds of thousands have been forced to flee their homes while access to essential services such as healthcare has become increasingly difficult.

Médecins Sans Frontières / Doctors Without Borders (MSF) teams already working in Sudan have been responding to the crisis since its first moments.

Our healthcare projects and hospitals – in some places the only medical facilities still open – have treated influxes of critical patients: the war-wounded, pregnant women in labour, and chronically ill people with nowhere else to go. At the same time, MSF teams in neighbouring Chad have received huge numbers of injured refugees who have travelled for miles to reach urgent care.

As Sudan’s war enters its third year, the humanitarian crisis is spiralling. Sixty percent of the population, around 30 million people, need humanitarian aid. Yet the response remains insufficient: underfunded, deprioritised, and stalled by a lack of political will.

MSF urges that Sudan must not become a forgotten crisis.

The current situation in Sudan: Latest news and stories

How can I help MSF in Sudan?

Right now, our teams in Sudan are treating patients injured or affected by the conflict. This is only possible because of donations from people like you.

By giving to our general funds today, you will be helping ensure we can respond to emergencies around the world, including in Sudan.

Please donate today to support our emergency teams.

Click here to learn more about how we spend your money

What is happening in Sudan?

- Relentless violence

Since the SAF took over Khartoum in May 2025, fighting intensified in El Fasher which has become the epicentre of atrocities, with alarming trends of ethnically motivated attacks and killings. This adds to the tight siege of the city and its nearby displacement sites for over a year. From May to July 2025, MSF teams treated 7,943 patients in the Emergency Room of the Tawila Hospital, an increase of nearly 30 percent compared to the previous three months.

- Millions of people have fled their homes

As of September 2025, nearly 12 million people have been forcibly displaced since the conflict began. This includes more than 4 million fleeing to seek safety in neighbouring countries such as South Sudan, Chad and Egypt. Displaced people across the country and region are now sheltering in crowded and often precarious conditions.

- Healthcare is under attack

Horrific attacks on healthcare in Sudan are leaving civilians without lifesaving care. As of June 2025 at least 622 attacks on Sudan’s healthcare system were recorded, with 157 facilities damaged, 147 health workers killed, and 104 injured. Around 70–80 percent of health facilities in conflict-affected areas of Sudan are either non-functional or barely operational. In 2025 alone, MSF has documented over 65 violent incidents targeting its staff, facilities, vehicles, and supplies.

- Humanitarian aid is being deliberately blocked

A staggering 30 million people are estimated to need humanitarian assistance in Sudan and MSF has been working with the Ministry of Health to treat some of this vast number of people who require urgent medical care. However, the Government of Sudan has repeatedly and deliberately obstructed humanitarian aid, especially to areas outside of SAF control.

- There is a catastrophic food crisis

The conflict has disrupted food supply across Sudan and people have been cut off from their jobs, meaning millions now face a new crisis: hunger. In March 2025, humanitarian organisations (including MSF and the UN) conducted a rapid assessment and reported 38 percent of children under five in El Fasher displacement sites are acutely malnourished. Across Sudan, the condition is widespread an rising. Over 8.7 million people face emergency or famine-level food insecurity as staple prices soar 430 percent.

- Pregnant women and children are dying in shocking numbers

In a crisis within a crisis, women and children are facing dangerous but preventable conditions. One MSF report found a staggering mortality rate among pregnant patients, driven by malnutrition, unsanitary environments and the collapse of everyday healthcare.

- Infectious disease outbreaks

Sudan is in the midst of a cholera outbreak, first declared in August 2024. Since then, Sudan’s Ministry of Health has reported over 99,700 suspected cases and more than 2,470 deaths. Initially concentrated in the east of the country and reported earlier this year in Khartoum, the outbreak has since expanded westward, with Darfur becoming a major hotspot since June 2025. Today, the situation is particularly critical in South, Central, and North Darfur.

Read: Why is no one talking about the biggest humanitarian crisis on Earth?

What is MSF doing in Sudan?

MSF works across Sudan with a team of more than 1,400 Sudanese and international staff. Right now, our expert teams:

- Provide emergency treatment and carry out surgeries, including trauma care, for war-wounded and non-war-related injuries

- Run mobile clinics for displaced people sheltering in camps and at transit sites

- Provide safe maternity and paediatric healthcare

- Run therapeutic feeding programmes for children suffering from malnutrition

- Treat infectious diseases and deliver vaccination programmes in response to outbreaks

- Provide mental health support for survivors of sexual and gender-based violence

- Deliver essential safe water and sanitation services

- Donate critical medical supplies and equipment to healthcare facilities, and provide training and logistical support to Ministry of Health staff

1,061,200

OUTPATIENT CONSULTATIONS BY MSF IN SUDAN IN 2024

20,400

BIRTHS ASSISTED BY MSF IN SUDAN IN 2024

11,300

CHILDREN ADMITTED TO INPATIENT FEEDING PROGRAMMES BY MSF IN SUDAN IN 2024

Background to the Sudan war and crisis

Following a military coup in 2021, most international aid to Sudan was frozen. This led to an economic crisis and increased food insecurity.

Sudan’s healthcare system was also extremely fragile even before the recent escalation in violence and access to basic medical services has been a challenge for most people.

This critical situation has been caused by a combination of recurring violence and conflict, the economic situation and the cost of healthcare, and an overall lack of medical staff and resources.

Added to this, the sharp decline in international aid has had consequences including reduced vaccination coverage and increased malnutrition among children.

Before the conflict, around 78,000 children under five were dying each year due to preventable causes such as malaria. In the first four months after 15 April, around 50,000 children with accurate malnutrition had their treatment disrupted.

Sudan also already had a high maternal mortality rate, with around 25 percent of births unattended by a skilled healthcare professional.

The stark reality is that Sudan’s healthcare system has been on the verge of collapse for decades. However, with the rapidly deteriorating humanitarian and security situation, low-running supplies and under-pressure staff, it is now at breaking point.

MSF in Sudan before the conflict

MSF has been working in Sudan since 1979. We have been providing medical aid throughout the civil war that led to the split with South Sudan in 2011, and the decade-long conflict in the Darfur region.

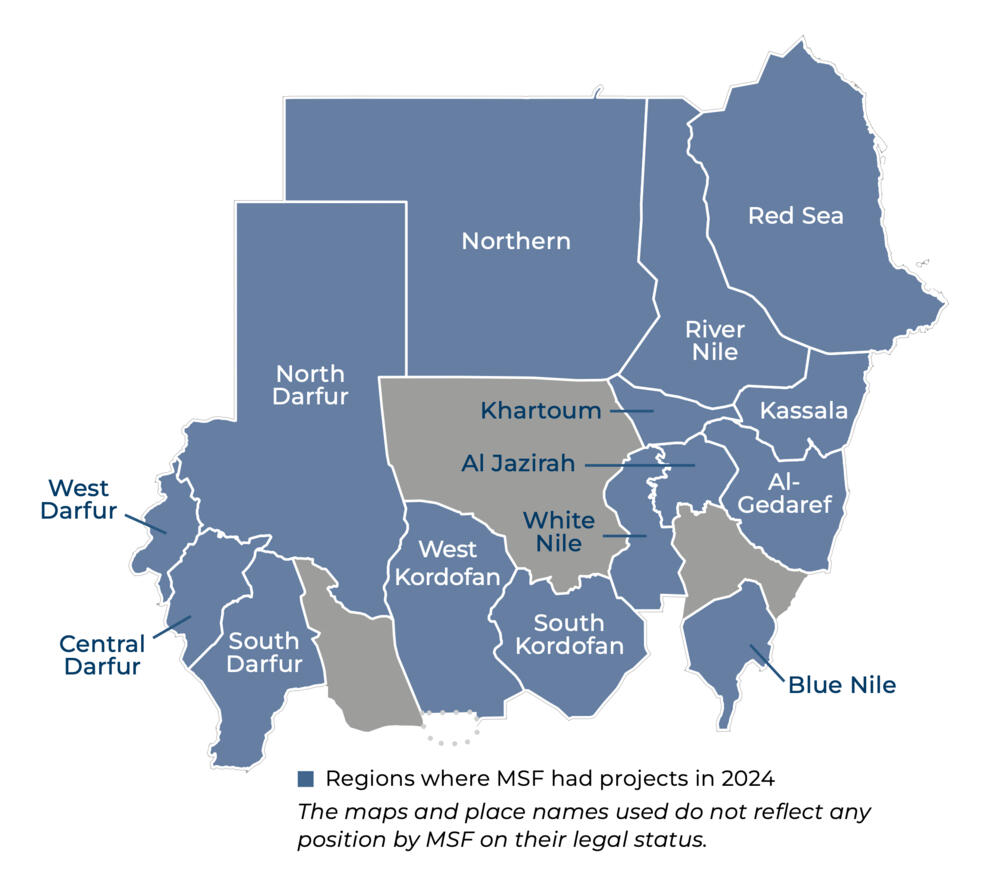

Before the recent escalation in violence on 15 April 2023, we were running 11 medical projects across 12 states. This included 24 healthcare facilities, from mobile clinics to hospitals.

In 2022, MSF teams in Sudan held 449,654 outpatient consultations, admitted 21,664 people to hospital, treated 5,621 children for malnutrition and assisted in 2,791 deliveries.