“A sign of how far we have to go”: Former local doctor becomes one of MSF’s first black African medical directors

"I can’t pretend I’m unaware that I’ll be one of the first black Africans who started as local staff to take on the role of MSF medical director. That in itself is a sign of progress, but at the same time, it’s a sign of how far we still have to go."

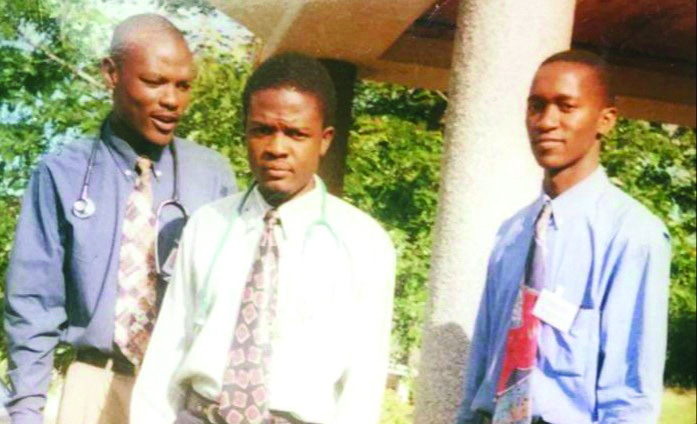

Bern-Thomas Nyang’wa was the first Malawian doctor to work for MSF; today, he is MSF’s medical director. He describes a life in which he has consistently pushed the boundaries.

I was born in Lilongwe in Malawi, the sixth of seven children. My grandfather worked as a doctor and my older sister was a nurse, but growing up, what I most wanted was to play professional basketball.

Back in the 1980s, Malawi was under the dictatorship of Hastings Kamuzu Banda. My boarding school, Kamuzu Academy, was set up by him. His aim was to select two or three people from each district and mould them into the future leaders of Malawi. The school was very strict in lots of ways but it was positive in that it really pushed you to your limits.

I had one very inspiring teacher: a British man called Mr Harwood who taught biology. He kept me focused and his passion helped me understand certain complexities, not only of education but of life as well.

“He believed in me more than I did myself and never allowed me to settle for anything less than the best”

The biggest influence on my early life was my dad, who died when I was 18.

He believed in me more than I did myself and never allowed me to settle for anything less than the best. He fully supported my plan to become a doctor. My route into medical training was expensive, but my dad said: "If you want to do medicine, we will find some money to pay for it and I’ll help you get there."

“I wanted to help people”

At that time in Malawi, there were not many professions where you could make a difference and earn a decent living – which was why I chose medicine. In particular I wanted to help people with HIV.

HIV had a very big impact in southern Africa in the late 1990s and early 2000s. There was still no treatment for the disease and life expectancy in Malawi was just 45 years. I knew so many people of my age whose parents had died of it.

In 1998 I started at the College of Medicine in Blantyre. There were just 14 of us in the year.

Five years of hard work later, I graduated. I remember that feeling of combined relief, excitement and pride – it was really quite a moment.

We all had to do an 18-month-long internship in Malawi’s central hospital in Blantyre, taking turns in all the different departments.

We worked around the clock, sometimes for 72 hours at a stretch, and were paid pretty much nothing. I didn’t have much of a life outside the hospital but, looking back, I can see that I learnt a lot in those months when I was really being pushed to the limit.

Paradise for a doctor

During the last months of my internship, I heard of MSF for the first time. MSF was running an HIV project nearby in Chiradzulu and needed someone to cover for one of their doctors.

Knowing very little of MSF, I thought I’d go there for a couple of weeks and make some money. But when I got there, I found it was pretty much paradise for a medical doctor.

“In the central hospital in Malawi, you knew that 90 percent of your medical patients had HIV. You knew you were just treating whatever acute illness they had.”

In the central hospital in Malawi, you knew that 90 percent of your medical patients had HIV. You knew you were just treating whatever acute illness they had and that, after a few months, they would come back and would probably never go home.

With MSF in Chiradzulu, I had all the drugs I needed and I could prescribe antiretrovirals, which at that time were only available in the private sector and cost a lot of money. But here, in this rural health centre, all I had to do was prescribe them. I had everything I needed to actually manage patients.

I also had a really good team. Together we discussed what we saw and what could be improved. They were very interested in what I had to say. I realised I was the first Malawian doctor to work for MSF.

After finishing my internship, I got a job with MSF. Over the next two and a half years, I treated hundreds and hundreds of patients and did thousands of consultations in Chiradzulu.

At the same time, I worked my way through the various roles within MSF: as a doctor, as a medical team leader and then as deputy medical coordinator.

I felt ready to be a medical coordinator but was told point-blank by MSF that I could not do this job in Malawi, because of its different rules for local and international staff. A lot of people in MSF still face these structural barriers to progress. My only option would be to do the job elsewhere.

Even though this was not part of my plan, I was forced to leave Malawi.

On the road

Nigeria, on the other side of the continent, was a big change. The culture in western Africa is very extroverted – a complete contrast to Malawi’s laidback culture.

I was hospital manager of a trauma centre in Port Harcourt. The pace was very fast-moving: you needed to make decisions quickly and know when to stand your ground.

I had to learn to put my foot down and say: “This is how we are going to do it.”

We had the opportunity to push the boundaries of internal fixation surgery within MSF.

The hospital was getting too full of patients, so we needed to find a way of treating patients and sending them home safely. People felt that you could not do internal fixation surgery in this setting, but we said we didn’t have a choice and proved it was possible.

Next I went with MSF to Chad. There were major security issues. We had a mishap – we were attacked in one of the camps – and it was so traumatic that I decided to leave, going instead to the Central African Republic to set up a tuberculosis (TB) and HIV programme.

Get closer to the Frontline

Get the latest news, stories and updates, straight to your inbox.

TB breakthrough

After the Central African Republic, I got married and considered that my chapter with MSF was closed.

My wife, a year above me in medical school, was in the middle of doing her specialisation as a paediatrician in the UK, so that’s where I went. I was happy just to be with my wife. I thought I’d do some training in the UK too, then probably work in the NHS.

Hear Bern talk about MSF's TB research project as part of this video explainer

But then I heard that MSF UK’s Manson Unit had a vacancy for a TB implementer. It was an exciting job and a good transition for me: we’d spend four to six weeks at a time at MSF’s projects in Central Asia or Eastern Europe, where multidrug-resistant TB (MDR-TB) was a growing problem.

Through these visits, we saw the challenges of treating patients for MDR-TB, because the only drugs available were highly toxic and had severe side effects. This led to the TB-PRACTECAL project – a multi-country clinical trial into new, shorter and more effective treatment regimens for drug-resistant forms of TB.

I was project manager and later chief investigator for the trial. I’m very proud of the progress we’ve made and the care we are giving to patients in the trial: we’ve treated 500+ patients with MDR-TB with really good outcomes.

“I can’t pretend I’m unaware that I’ll be the first black African who started as local staff to take on the role of MSF medical director”

In the 12 years since I moved to London, I’ve done a Masters’ in Public Health, I’m completing a PhD at the London School of Hygiene and Tropical Medicine and I’m an honorary lecturer at UCL’s Institute for Global Health.

I really enjoy trying to mix the robust thinking and reflectiveness of academia with the pragmatism of MSF.

A sign of progress

After all my years with MSF, I still feel its passion – the friendships and the respect, the focus, the ability to push for what is best for our patients – and I hope to take this passion into my new role as medical director of MSF.

I’m excited and honoured that MSF has entrusted such an important role to me.

I can’t pretend I’m unaware that I’ll be one of the first black Africans who started as local staff to take on the role of MSF medical director. That in itself is a sign of progress, but at the same time, it’s a sign of how far we still have to go.

MSF has a lot of local staff who are really invested in MSF – they could have done this long before me. But I’m optimistic about the current momentum within MSF to value and nurture the potential of our staff, regardless of their geographical origin, and I hope I will add to that momentum and the delivery of it.

Most of all, I’m looking forward to really being of help. Although a medical director is a couple of steps removed from the day-to-day activities in MSF’s projects, I’m driven by the fact that whatever I do will have a positive impact on the patients that we serve, and I’m determined to do this with all my energy.