Measles: “If vaccinations don't happen, the effects will be felt for years”

Measles epidemics hit Niger annually, but this year’s outbreak is skyrocketing – the result of insecurity and the knock-on effects of COVID-19.

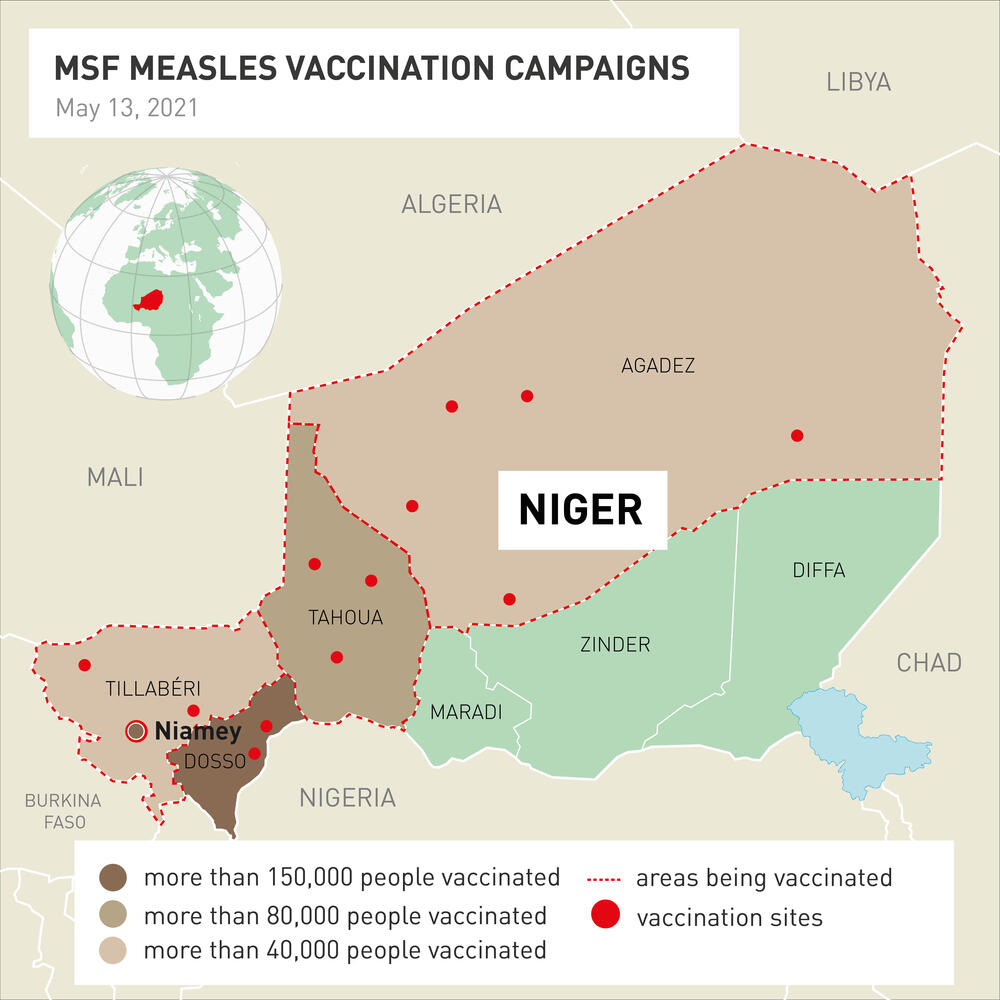

Médecins Sans Frontières / Doctors Without Borders (MSF) teams are now three months into a mass vaccination campaign, aiming to protect more than 700,000 children from the world’s most contagious viral disease. Leading this life-saving work, project coordinator François Rubona shares the situation on the ground.

This year, we have seen the number of people affected by measles increase exponentially compared to last year.

In the first three months of 2021, the country recorded 3,213 cases of measles, compared to 1,081 in the same period last year. This means that cases have almost tripled.

By April, Niger had had more than 6,000 suspected cases of measles including 15 deaths, and an epidemic had been declared in 27 of 73 districts. The most affected are the regions of Agadez, Dosso and Tahoua.

The world’s most contagious virus

Measles is the world’s most contagious viral disease and one of the main causes of death in young children.

The most effective way of tackling measles is to ensure 95 percent of a community are vaccinated, according to the World Health Organization. However, in Niger, data from some of the affected districts suggests vaccination coverage is 50 percent at best.

In areas such as Diffa, Tillabéry and Tahoua, the low coverage can be explained by worsening insecurity which has led to people being displaced from their homes, making it more difficult to access basic healthcare.

This year’s measles epidemic has also been amplified by the COVID-19 pandemic, which has created new constraints for routine and catch-up vaccination campaigns.

An epidemic in the pandemic

When the first COVID-19 cases were declared in Niger in March 2020, fears surrounding this unknown disease probably led to a decrease in visits to health centres. As a result, fewer mothers brought their children in for routine vaccinations.

The pandemic has also affected health workers, as some staff have tested positive or have had to self-isolate. This has meant clinics can no longer run at full capacity and have been forced to reduce some activities, especially preventative care.

At the same time, over the past year the government and organisations, including MSF, have had to focus on tackling the pandemic, further impacting this.

At times, border closures and restrictions have made it more difficult to import medical supplies.

However, this year we have still managed to ship 700,000 doses of measles vaccine into the country, in order to respond to the current epidemic as well as build an emergency stock.

Help us prepare for the next emergency

Vaccine hesitancy

Over recent weeks, we have seen a low number participating in some neighbourhoods where we ran vaccination campaigns. This is due to confusion between measles and COVID-19 vaccinations.

In Tillabéry, for example, some communities have completely refused to be vaccinated. In Niamey, too, our teams have met with some vaccine hesitancy, linked to rumours that measles and COVID-19 vaccines were being given simultaneously.

In April, during those first few days of our campaign in Tillabéry, our teams recorded a coverage rate of just 4-5 percent of their daily target.

Measles: Our work in numbers

147,985

PEOPLE TREATED FOR MEASLES BY MSF IN 2023

3,295,700

VACCINATIONS AGAINST MEASLES BY MSF IN RESPONSE TO AN OUTBREAK IN 2023

95%

OF MEASLES DEATHS OCCUR IN LOW-INCOME COUNTRIES

So, we have reinforced our community engagement and outreach work in order to help families understand how measles can affect children’s health, and how vaccinations can protect them and stop the disease from spreading.

A rising risk

The current measles situation in Niger is worrying. It highlights the consequences of a decrease in vaccine coverage and routine vaccination work.

We now fear a rise in the epidemic risk for all other diseases that can usually be avoided through vaccination. For example, we have seen patients with symptoms of meningitis in Niamey and more than 1,100 cases have already been recorded across the country.

If routine and catch-up vaccinations fail to happen regularly, the effects of this decrease in coverage will probably be felt for years to come.

At the same time, as the seasonal peaks for malaria and malnutrition draw closer, we are monitoring the situation closely. Last year’s malaria peak was particularly damaging, as it was both higher and lasted longer than usual – it didn’t end until January 2021.

Taken alongside highly worrying forecasts regarding food security and malnutrition, we have to be extremely vigilant. This includes in regions such as Maradi and Zinder, which are often neglected by organisations due to being further from the epicentre of armed conflict and its consequences.

MSF and measles

Measles is a highly contagious viral disease and one of the leading causes of death among young children.

A safe and effective vaccine has existed since the 1960s but outbreaks still occur due to ineffective or insufficient immunisation programmes.

While global measles deaths have decreased by 73 percent worldwide in recent years – from 536,000 in 2000 to 142,000 in 2018 (according to the World Health Organisation) – measles is still common in many developing countries, particularly in parts of Africa and Asia.