Innovation: The unique programme protecting children against malaria

In Burundi, malaria has been the leading cause of hospitalisation and death among children for years. To improve young patients' chances against this life-threatening disease, MSF has introduced an innovative ‘triple protection’ approach in one of the country’s most affected regions.

Malaria is a major public health issue in Burundi. In this East African country of around 14 million people, several million cases are reported each year. According to the World Health Organization (WHO), more than 1,800 malaria-related deaths were recorded in 2023, mainly among children under the age of five.

Many factors contribute to the scale of the disease. So, to combat it, the health authorities and their partners have been trying various strategies over the years: mosquito net distribution, preventive treatments, indoor spraying, and—since the end of 2024—the introduction of malaria vaccination.

Most recently, Médecins Sans Frontières / Doctors Without Borders (MSF) and the Ministry of Health have launched a unique initiative in the country, combining three preventive measures on a large scale at the same time. Their focus? One of the health districts most affected by malaria: Cibitoke.

Medical care where it's needed most

Help us care for people caught in the world's worst healthcare crises.

A new layer of protection for children in Burundi

MSF is working with 20 centres in the district to roll out a new way to protect young children from malaria.

At each centre, children receive four doses of the malaria vaccine between the ages of six and 18 months. Families are also given a mosquito net treated with insecticide when their child received the first dose.

From nine to 24 months of age, children also receive preventative tablet-based medicine to give them extra protection.

At the Kaburantwa Medical Centre, eager parents and their children form a queue in front of the vaccine service.

“When he was younger, my son often suffered from malaria. He was even hospitalised and had to receive a blood transfusion”

Combining approaches for better protection

“When he was younger, my son often suffered from malaria. He was even hospitalised and had to receive a blood transfusion,” says Claudine Tuyishimire leaving the centre after getting her nine-month-old daughter Fanny vaccinated.

“When they explained the protection available today, I didn’t hesitate. I came straight away. Thanks to this, children will rarely get sick, and parents will no longer have to come to the hospital so often.”

At all the centres using this approach, the response has been positive. Waiting rooms are full.

This high turnout is the also thanks to the community health workers, who raise awareness and follow up with families and associations, particularly women's groups.

95%

In 2023, an estimated 95 percent of the 597,000 global malaria-related deaths occurred in Africa.

“The scale of the problem, as well as the costs the disease imposes on households, are generating strong enthusiasm within communities,” says Adélaïde Ouabo, MSF coordinator in Burundi.

“The medical costs of treating malaria, especially in its severe forms, are a heavy burden on families and on the Burundian health system. These massive costs contrast with the low investment required to implement the triple protection strategy.”

MSF's work with the Ministry of Health in Cibitoke shows that this system is both simple and low-cost but delivers big results. Vaccinations and mosquito nets are already integrated into the health system, and preventive medicine is affordable. That makes this approach easy to continue and possible to expand to other parts of the country.

Zakari Moluh, MSF project coordinator in Cibitoke says, “this district is among those with the highest number of malaria cases and deaths, and our teams have already intervened there in emergencies to respond to outbreaks.”

“To provide a more sustainable response, we proposed a pilot approach to the authorities: protecting all children through malaria vaccination, long-term preventive treatment, and the provision of insecticide-treated mosquito nets, all at the same time.”

Why treatment still matters

MSF teams have observed a significant decrease in people admitted for malaria since the third quarter of 2025, especially for severe cases at Cibitoke District Hospital, which saw a drop of over 40 percent.

To better understand how effective the strategy really is, an MSF research team has been studying the impact of the combined approach over several months. The results will help health authorities and partners in Burundi make informed decisions about malaria control.

“In a context of resource rationalisation, linked to the overall decline in humanitarian funding, making the most effective and scientifically proven choices is absolutely essential,” says Adélaïde Ouabo.

“We are happy to contribute to this effort.”

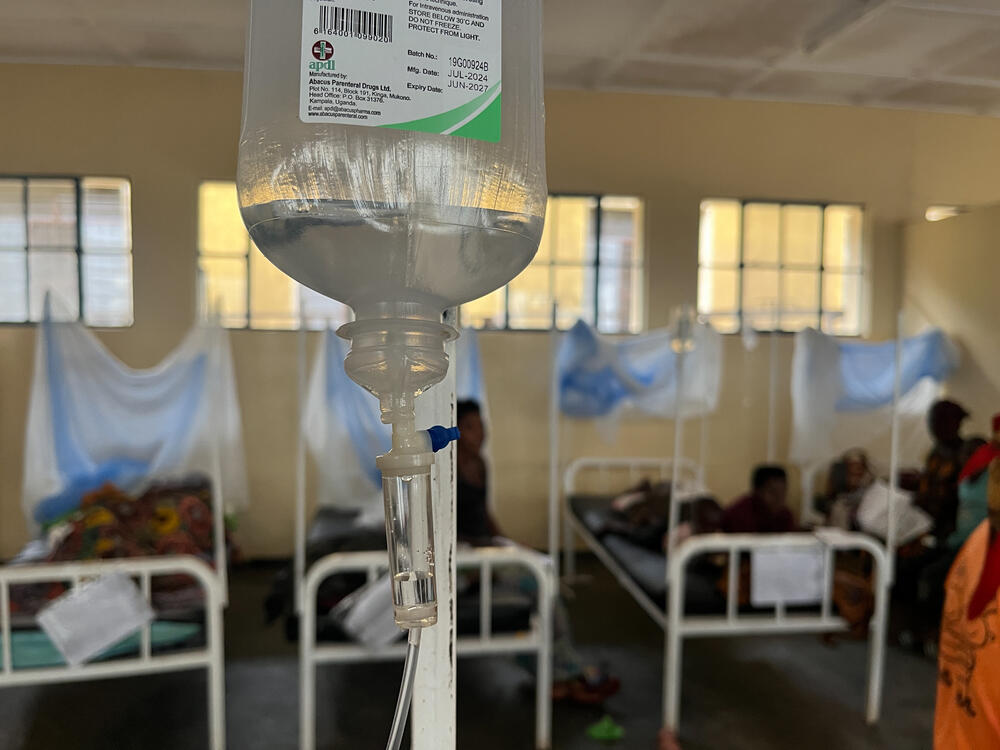

Preventing malaria is the main goal, but treating sick children remains just as urgent. MSF continues to work with health authorities to ensure children receive the care that they need.

In remote villages, MSF-trained community health workers can quickly detect malaria symptoms, perform rapid tests, and start treatment if the result is positive.

More serious cases are referred to one of the MSF-supported health centres, where medical supervisors help strengthen care delivery.

In emergencies, an ambulance is available to transfer patients to the district hospital in Cibitoke. There MSF teams support the management of the most severe cases, especially in children, with staff dedicated to training and mentoring local doctors and nurses.

The disease remains a major emergency across much of the continent, especially in Sub-Saharan Africa. MSF is committed to supporting both prevention and treatment in the fight to change that.

MSF in Burundi

In Burundi, Médecins Sans Frontières/Doctors Without Borders (MSF) has responded to endemic and epidemic diseases, social violence and healthcare exclusion, and has run a trauma hospital in the capital Bujumbura. We are also helping tens of thousands of Burundians who have fled across the border to Tanzania.

One of our main focuses in Burundi is tackling malaria, the leading cause of death in the country. In addition to providing treatment, we collaborate with the health authorities to implement measures to reduce the incidence of the disease.