Sudan: The technology putting refugees on the map

Reaching remote and vulnerable places with emergency medical aid requires an accurate map. Andries Heyns explains how specialist 'GIS' tech has helped treat people fleeing from Tigray in Sudan's evolving refugee crisis.

"Early in November 2020, conflict broke out in Ethiopia’s northern Tigray region and refugees started fleeing in their masses to neighbouring Sudan. The journey requires crossing up to 350 km of mountainous terrain over days and weeks, in dry conditions with temperatures regularly exceeding 35 degrees Celsius.

Lacking basic resources like food and water, carrying only what they can, carrying their children and those too weak to walk, they arrive in Sudan exhausted and dehydrated. As if this isn’t challenging enough, they also carry the trauma of seeing their families killed, their livelihoods destroyed, and having their futures cut short.

With no short-term solution to the situation in sight, these refugees are settling in challenging, resource-scarce environments, with no idea of what the future holds for them.

At the end of that same month, I joined the Médecins Sans Frontières / Doctors Without Borders (MSF) team in the refugee camps in Sudan, providing support as a geographic information system (GIS) specialist.

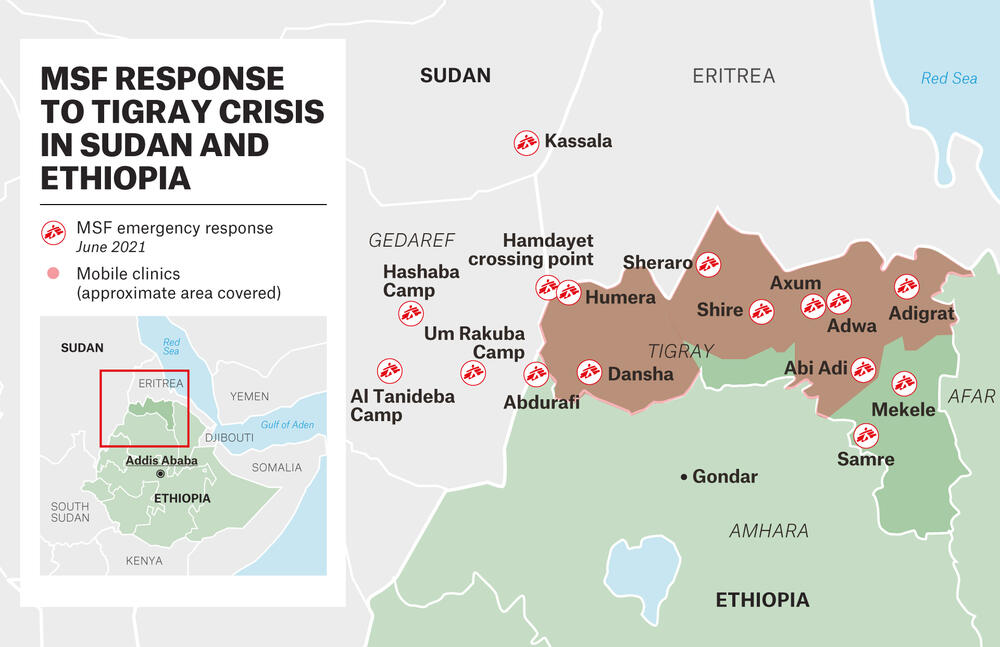

I arrived in Sudan early in December and stayed for a total of 10 weeks, returning mid-February 2021. I was based in Gedaref, from where I visited refugee camps in Hamdayet, Al-Hashaba, Umm Rakouba and Al-Tanideba.

Hamdayet and Al-Hashaba are, in theory, transit camps – refugees arrive here first, register and stay temporarily after which they are relocated to the permanent camps, namely Umm Rakouba and Al-Tanideba. However, in reality, people were forced to stay much longer.

What is geographical information important?

When we know where people are and where the immediate needs are most urgent, MSF's medical teams can plan more effectively to make sure they're reaching people with the right care and services.

A map can tell a visual story and provide context and scale within a single image.

Comparing maps over different time-frames provides insight into the progress of humanitarian aid activities and the growth of the camps. This means they are a great way for planners and decision-makers who are not actively on the ground to stay informed about the evolution of the situation. Detailed and up-to-date maps can provide a concise summary of the big picture.

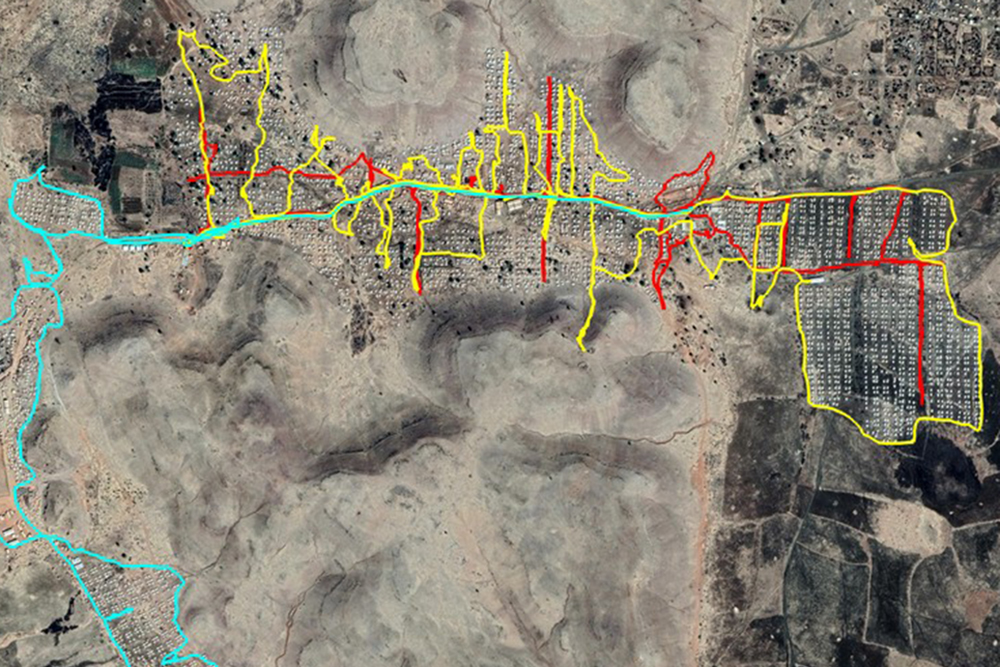

However, with refugees arriving on a daily basis, the picture in Sudan is constantly changing and needs regular updating so that a current snapshot is available at all times. This meant I spent a lot of time crossing refugee camps on foot, with a bag full of water on my back, two smartphones for data collection (one spare just in case), sunscreen, and some snacks.

Help us prepare for the next emergency

Working as a GIS specialist, my main responsibility was to collect spatial data that our teams could use to monitor the situation in the camps, and to manage MSF's activities effectively.

Traversing the camps, I gathered the GPS coordinates of points of interest, like the location and condition of water and sanitation facilities, the locations of other agencies (UNHCR, World Food Programme, Red Cross, etc.), and the rapidly changing extents of the camp boundaries.

Sometimes I would draw mini-maps and take photos I could refer back to later. At the end of each day, I would then transfer and process all this data to put onto maps that could be used by our teams.

Helping hands

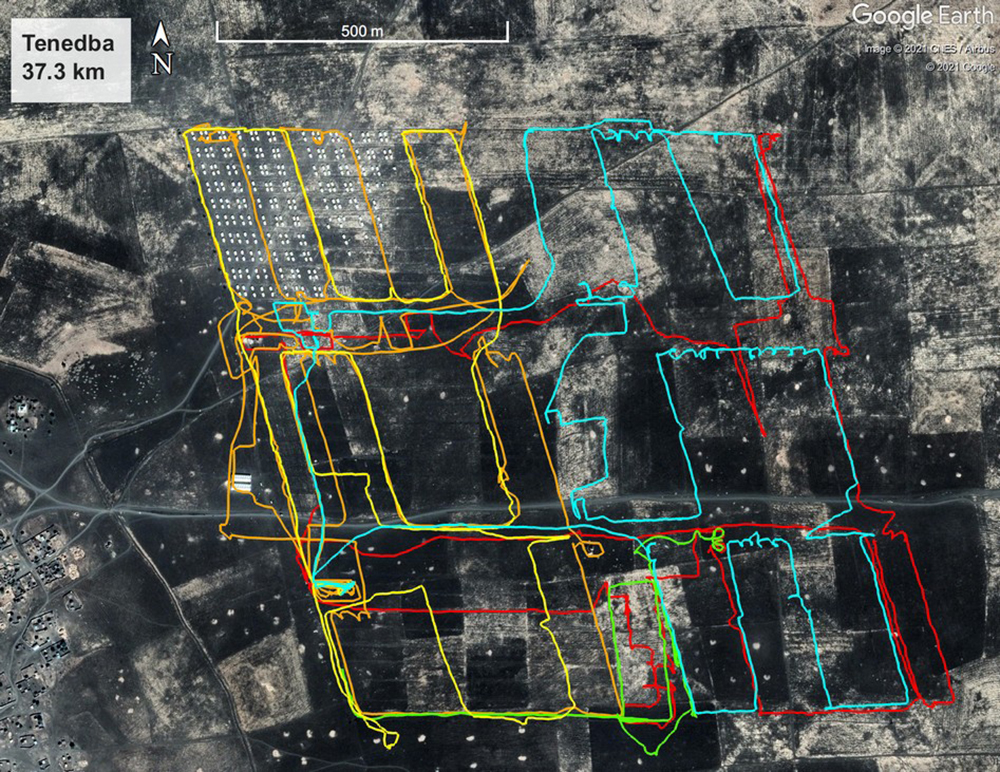

In the time I was there, camps like Umm Rakouba and Al-Tanideba were receiving refugees from Hamdayet and Al-Hashaba and were evolving at an astonishing pace. This meant I had to visit more regularly, making constant additions and updates to the data points to keep the maps up-to-date.

Performing this work was physically exhausting. I generally walked at least eight kilometres each time I went to the camps, with temperatures normally above 35 degrees, and with no shade.

In total, I covered 94.5 km on foot in all my visits. However refugees arriving at the camps have generally walked well over twice this distance without rest, food or water, and in fear for their lives and their families.

While the work was demanding, it was often eased by my colleagues. I regularly received GPS coordinates from other team members from the various camps, which I then turned into maps and sent back to them.

The wider network of GIS specialists in MSF also came to my aid, for example by obtaining satellite data and 'dwelling density analyses' of the camps. These analyses helped team members on the ground to estimate the refugee population size and their distribution, which makes a real difference when it's time to determine the gathering points for activities like vaccinations.

In numbers: Refugees and displaced people

120 million

PEOPLE DISPLACED WORLDWIDE

32 million

REFUGEES ACROSS THE GLOBE

Every 2 seconds

A PERSON IS DISPLACED

Back at the base in Gedaref, power cuts came and went unexpectedly, generally lasting two or three hours, but sometimes lasting well over four hours. Internet access was very weak to non-existent most of the time, which was very challenging to deal with because I need internet to do my job.

However, having worked in humanitarian settings before, this wasn’t unexpected and it did not bother me too much – I was always able to get the job done, just with some delays here and there.

Just going with it

To get to the camps required long journeys through unique landscapes. I remember passing hundreds of camels being herded by small boys, and crossing a river by ferry to get to Al-Hashaba.

When you arrive at the ferry, there is no certainty if you will get on the next one or if you will have to wait longer, but everyone seems to accept that. That’s just the way it is, the pace of life is different and you just go with whatever happens.

My time back in Sudan made me realise that I want to do more hands-on humanitarian work and be more directly involved in emergency response planning and coordination.

I've therefore taken a step back from my academic research projects and recently started a new position as GIS and Missing Maps coordinator at MSF’s UK office, providing support to the epidemiology and public health team.

Even though my job is now primarily based in an office rather than in our medical projects, I’m always excited to assist our teams on the ground in collecting and preparing crucial data to support their activities. This not only makes work easier for the teams, but helps MSF achieve its primary goal: providing medical aid to vulnerable people."

MSF and the Tigray crisis

Tens of thousands of refugees have fled the Tigray region of Ethiopia after fighting erupted in early November 2020.

Our teams began triaging and treating war-wounded people on 5 November in the Amhara region of Ethiopia, then providing emergency medical care to people who have fled across the border into Sudan.