Mental health in South Sudan: “I was sick, not a criminal”

When 33-year-old Samat started experiencing symptoms of mental illness, he had few places to turn to. For World Mental Health Day this month, the MSF mental health team in Malakal, South Sudan, shares Samat's story and explains their approach to make sure that people like him are treated like patients, not criminals.

South Sudan faces a profound but often invisible mental health crisis. Decades of conflict, displacement, and poverty have left deep psychological scars.

Yet, with only a handful of trained professionals and virtually no specialised facilities, individuals in crisis are often stigmatised, neglected, or treated as criminals.

In places like Malakal in Upper Nile State, families with nowhere to turn sometimes feel their only option is to hand over relatives to the police.

Background

In South Sudan, ongoing insecurity and recurrent displacement continue to disrupt essential services, forcing communities to remain on the move and putting health staff and facilities at constant risk. This situation not only deepens the need for mental health support but also severely undermines the ability to deliver sustained care.

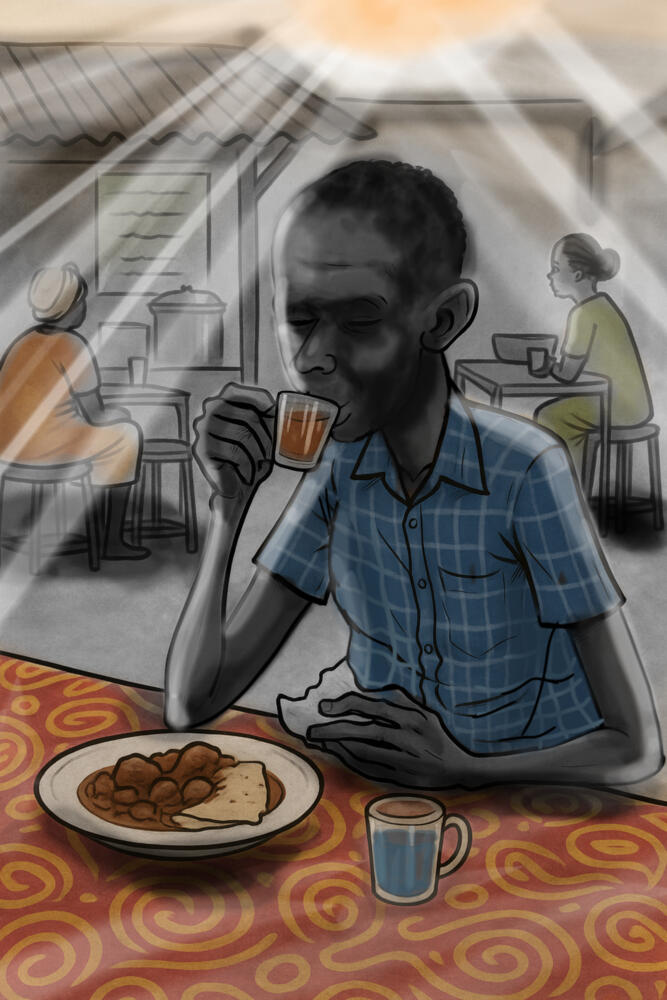

Samat's experience reflects the reality faced by many. He experienced a severe and sudden mental health crisis that distorted his reality and isolated him from the world he knew.

After a period of personal and financial hardship, Samat began hearing voices and losing touch with reality.

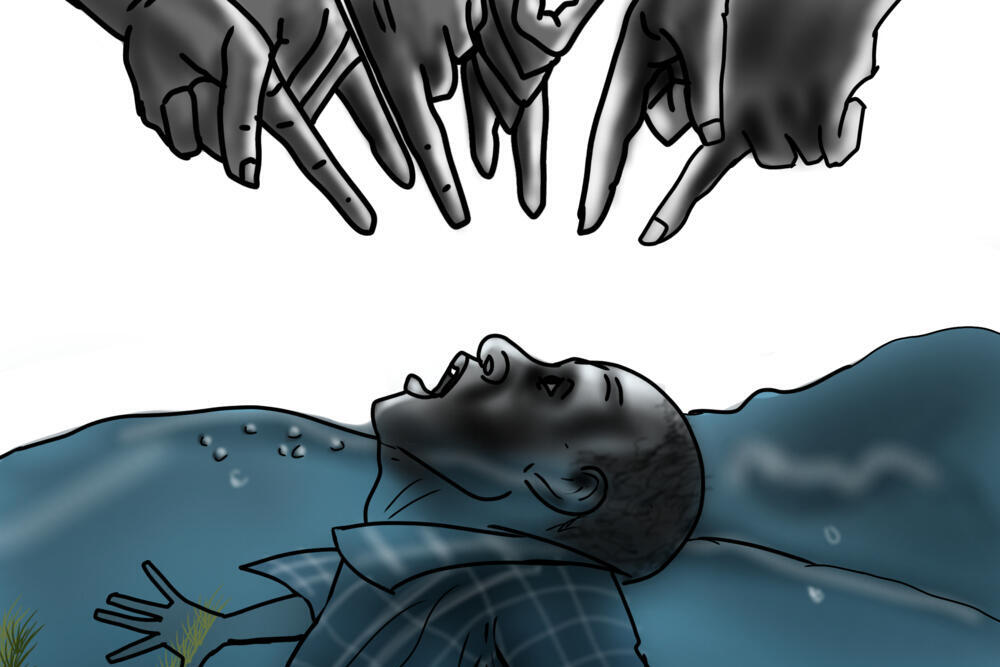

“While I was walking, my head started spinning. I heard voices, they were loud, talking to me. I couldn’t tell day from night, everything around me was dark.”

His mind created vivid, frightening illusions. He felt as if he was crossing a river where the water reached his neck, and he saw fingers pointing at him and heard voices telling him to drown.

What he perceived as a life-threatening struggle was, in reality, happening on a dry road, demonstrating the powerful and deceptive nature of his illness.

Following the voices, Samat walked away from home.

Help us prepare for the next emergency

A friend recognised his suffering and sought traditional help. A local elder provided a root, which offered a brief moment of calm, but it was not enough to silence the voices for long.

“My friend said, “You are not okay. Let me help you.” He took me to a traditional healer. The man gave me bitter roots to chew. I felt calm, but the voices came back again.”

761

Women provided with MSF mental health consultations in Malakal

369

Men provided with MSF mental health consultations in Malakal

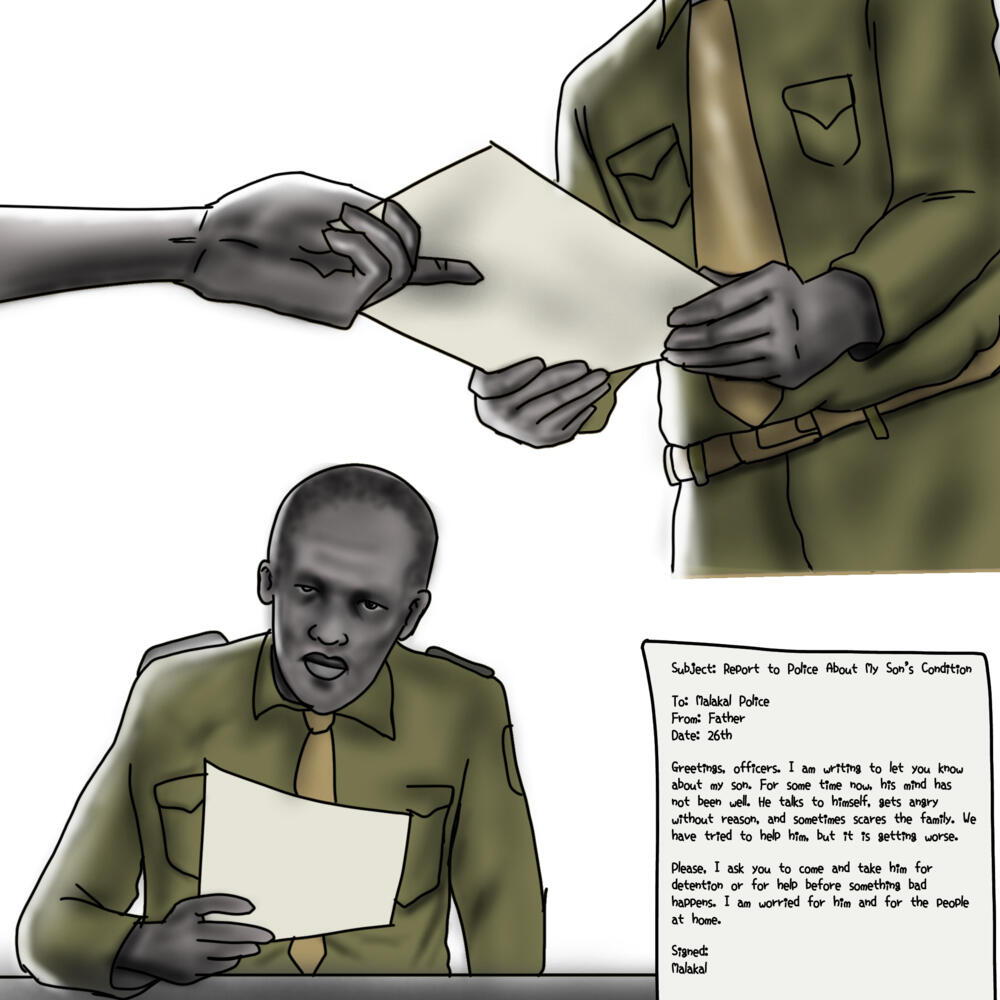

Fearing for his son’s safety and that of the family, Samat’s father, Nyuk, took the drastic step of reporting his condition to the local police.

He formally wrote a request that they take Samat for detention or help, a document that would alter Samat’s path.

“My father wrote a letter to the police, informing them that I was mentally ill.”

The police response was not medical, but custodial. Since there was no treatment facility for psychiatric patients, the only alternative was a painful one.

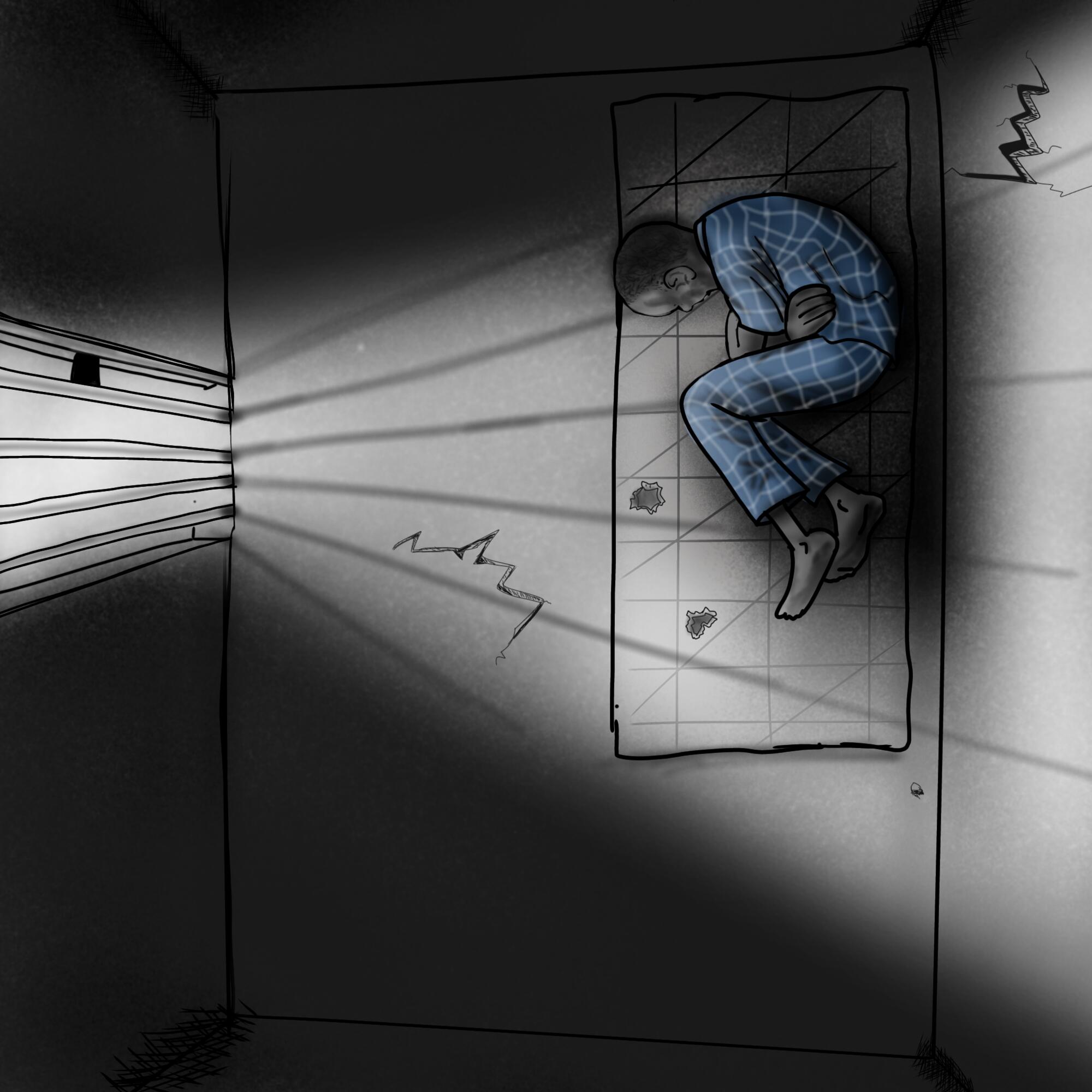

Samat was restrained in June 2025 and taken to Malakal Central Prison, where individuals with mental health conditions are often isolated in cells.

“They came, chained my hands and legs, and took me to prison. They said it was for my own good.”

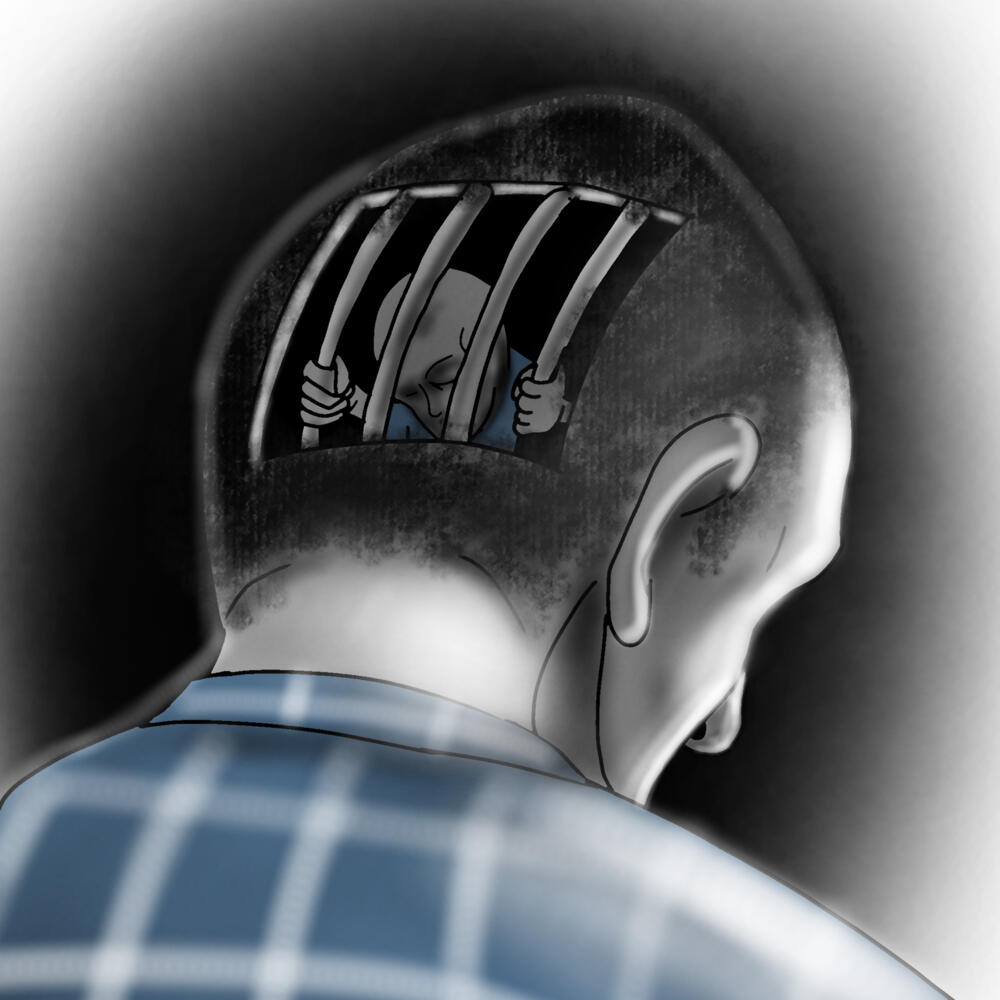

Samat was placed in a small cell in the prison’s isolated section for the mentally ill. His existence was reduced to a bare, monotonous, and profoundly lonely struggle for survival. He was put behind bars in a small cell, where mentally ill prisoners are isolated.

Every day was the same. One meal, only dry maize meal served daily at 3pm. No soup, no mosquito net, no bed, nothing warm at night.

His family never came to see him. He was completely alone.

“My family never came to visit me. I was completely alone”

Samat

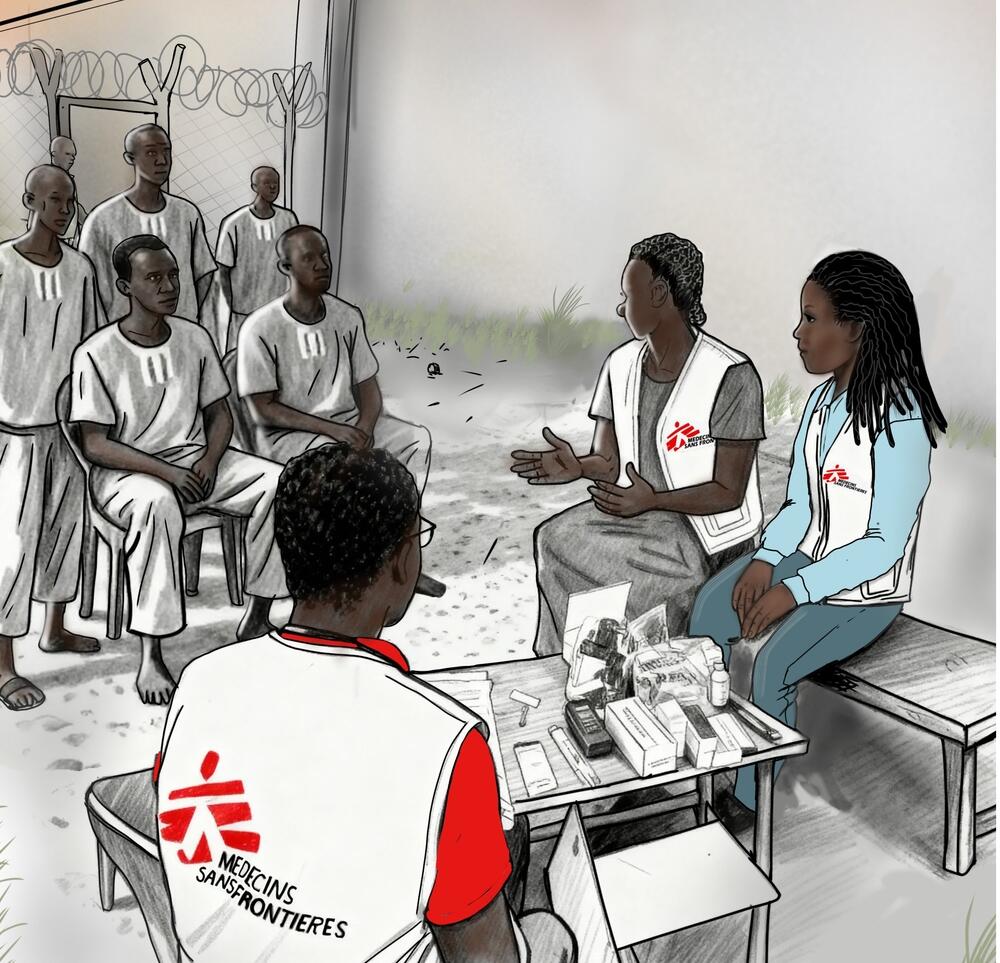

After days of this isolation, a mental health team from MSF arrived at the prison.

Their approach was different: they offered gentle words, a listening ear, and, crucially, medicine for a psychiatric condition he was suffering from.

"They listened, and gave us medicine. For the first time we felt seen not as prisoners, but as patients."

The MSF team provided psychiatric medication and consistent counselling.

Samat began a daily treatment regimen. The medicine helped, but the prison conditions made recovery a struggle.

The lack of food weakened him, making the side effects of the medication hard to bear.

Despite the hardship, the effectiveness of the treatment was undeniable.

Samat began to feel inner peace and a renewed hope for the future, the hope of recovery and eventual freedom.

After three months of imprisonment and two months of MSF care, Samat was released from Malakal Central Prison. He was free to reclaim his life and his autonomy in September 2025.

Today, Samat is regaining his strength and autonomy. His freedom and the continued support of his treatment is having a profound effect.

He is now focused on the practical steps of rebuilding his life, one day at a time.

Samat’s story is not unique and MSF teams in Malakal have seen children as young as 14 detained for untreated mental health conditions or minor infractions.

“Without appropriate services, families often see detention as the only option for relatives in crisis”

“Such practices underline a wider systemic failure: the absence of dedicated mental health facilities, limited referral pathways, and persistent stigma", says Laura Ximena, MSF Mental Health Activity Manager in Malakal.

"Without appropriate services, families often see detention as the only option for relatives in crisis."

MSF’s work has demonstrated that with medication, counselling, and consistent follow-up, recovery is possible. But progress is fragile without a functioning health system and social support.

“Mental health must be integrated into primary health care across South Sudan," says Laura.

"Community awareness and family engagement are equally critical. Above all, people with mental health conditions should be treated as patients deserving of dignity, not as criminals.”

Between January and September this year, 12 patients were seen by MSF admitted to contemplating suicide, primarily due to prolonged trauma, instability, inadequate psychosocial support, food insecurity, and exposure to violence.

April 2025 saw the highest number of cases, with four patients having attempted suicide and one holding thoughts of suicide.

“Prisons are no place for people with mental health conditions," says Samat. "What we need are hospitals, places where there is treatment, food, and hope for recovery.”

MSF in South Sudan

Médecins Sans Frontières/Doctors Without Borders (MSF) works in hospitals and clinics throughout South Sudan, where we run some of our biggest programmes worldwide.

As well as providing basic and specialised healthcare, our teams respond to emergencies and disease outbreaks affecting isolated communities, internally displaced people and refugees from Sudan.