Long read: The human cost of outsourcing Europe's borders

At least 60 percent of the asylum seekers trying to survive in the makeshift camps in Calais are Sudanese. Many have fled the ongoing civil war that broke out in Sudan in April 2023. Their testimonies highlight the systematic tightening of European migration policies, which continue to kill both inside and outside Europe.

Médecins Sans Frontières / Doctors Without Borders (MSF) teams are present throughout their migration journey, from Sudan to the UK, via Chad, Libya, the Mediterranean Sea and France.

“Living conditions in the ‘jungle’ are terrible,” says Ali. “In six months, I've been moved seven times because the police come to take away our tents. One day, I was woken up by police shouting at us. They told us to leave and threw our things in the rubbish. I stayed there, I couldn't move... They sprayed me with tear gas.”

Ali left Sudan in April 2023, just as his country was plunging into civil war. At the time, he was just a 19-year-old secondary school pupil trying to escape forced recruitment. When he arrived in Calais, he became one of the 1,000 to 1,300 people surviving in unsanitary camps with extremely limited access to food and water.

Like Ali, many of them fled Sudan after the start of the war between the Sudanese Armed Forces and the paramilitary Rapid Support Forces. Under international law, they can apply for protection as refugees in European countries.

France, Belgium and the UK have recently taken steps to facilitate the protection of Sudanese asylum seekers on their soil, given the catastrophic humanitarian crisis in Sudan. However, their testimonies reflect an entirely different reality, one of violence, insecurity, and uncertainty.

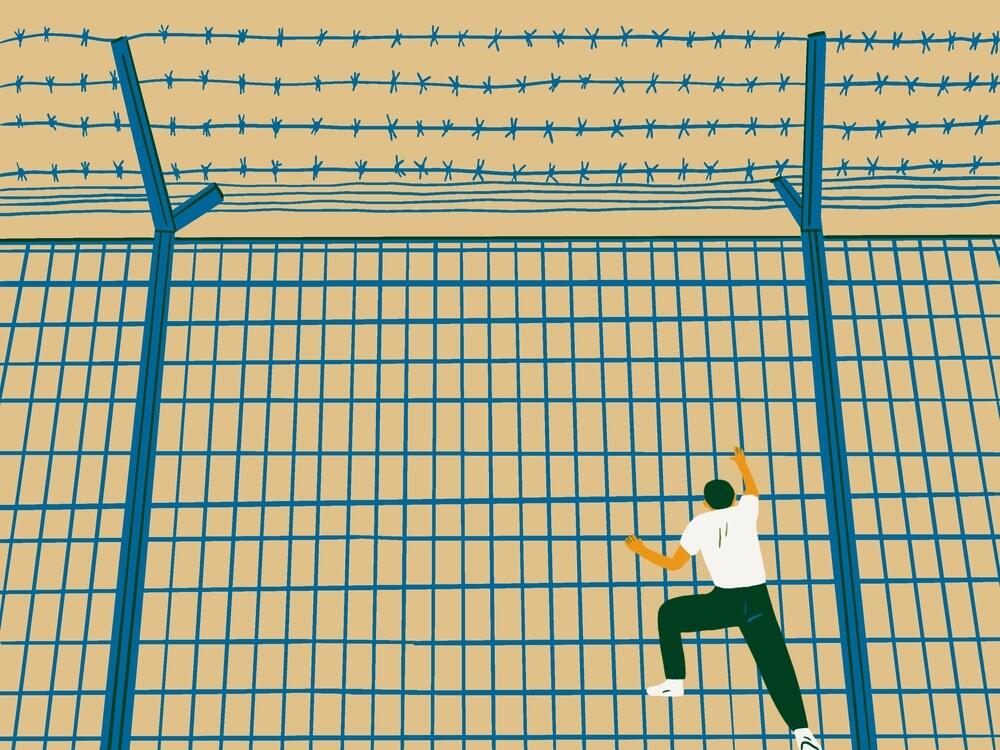

“I expected to be protected as a Sudanese in France. I expected the asylum procedure to be easier, but I felt like I was climbing a fortress,” continues Ali. “All my friends who have applied for asylum are still living in tents in the jungle”.

The situation of Ali and hundreds of other migrants is the result of decades of blocking migration by the European Union, and the fruit of its policy of outsourcing borders: entrusting part of the control of migration flows to third countries, via financial and material support or police and military assistance.

Far from curbing immigration into Europe, these harmful policies are the source of the most extreme suffering, witnessed by MSF teams in the countries where we operate along the migration route.

Medical care where it's needed most

Help us care for people caught in the world's worst healthcare crises.

Fleeing the war in Sudan

More than 10 million people have been displaced since the start of the war in Sudan, of whom 7.7 million have found refuge within the country itself and two million in neighbouring countries: 700,000 are currently in South Sudan, 600,000 in Chad and a further 500,000 in Egypt.

They have fled insecurity and violence, as well as a lack of food and water. In the huge Sudanese camp of Zamzam, near the town of El Fasher in North Darfur, alarming mortality and malnutrition rates well above emergency thresholds were measured in early 2024 by MSF teams among a displaced population of around 300,000 people.

In February, the MSF estimated that at least one child was dying every two hours in the camp, i.e. around 13 deaths a day. In March and April 2024, it was confirmed that a third of the children in the camp were suffering from malnutrition.

"When you see with your own eyes people, friends, loved ones lying in the street, dead or injured, and you can't even help them without risking death yourself, you can only look at them and weep"

Mustafa is a young Sudanese man now in Calais, who fled the ethnic massacres that took place in June 2023 in his hometown, El Geneina, in Sudan’s West Darfur state.

“I remember the day I left El Geneina. It was probably the worst day of my life,” says Mustafa. “When you see with your own eyes people, friends, loved ones lying in the street, dead or injured, and you can't even help them without risking death yourself, you can only look at them and weep.”

Since then, his family has taken refuge in Adré, in Chad, some 18 miles from the Sudanese border. But the student, who was planning to become a teacher, only stayed for a month. “Chad is a poor country, so I wanted to work, earn money and finish my studies,” Mustafa continues.

In the camps of eastern Chad, the sudden massive increase in the number of refugees has generated considerable humanitarian needs in all areas, from health to food aid, in an already difficult context for the local communities.

The existing refugee camps are saturated, with more than 100,000 people surviving in makeshift shelters in the border town of Adré, where MSF teams continue to provide medical care and water. In March 2024, they also responded to a hepatitis E epidemic in several camps, directly linked to a lack of water and sanitation infrastructure.

In these difficult conditions, some people prefer to continue on their way.

“I've heard that the European Union is now welcoming the Sudanese because of the war,” says Muntasir, a Sudanese refugee in the Goz Beïda camp in southeastern Chad. “But how do I get there? I have nothing, not even a (Sudanese) pound”.

The United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees (UNHCR) offers Sudanese refugees from these camps the possibility of registering for a resettlement scheme in a third country. However, the number of places to settle in European and North American countries is extremely low.

“Some people applied for resettlement in 2003 and never left. Legal immigration is too difficult,” explains Khalil, a Sudanese man in Tina, Chad.

The EU's subcontractors

The situation is similar in Libya, where only 1,100 asylum seekers managed to leave the country legally in 2023 thanks to UNHCR. Like more than 40,000 Sudanese since the start of the civil war, Ali went to Libya, a historic immigration destination for people from neighbouring countries looking for work.

“I went to Libya with my uncle,” recalls Ali. “We intended to work and live there, because it’s a rich country and we had a chance of finding a good job. Going to Europe was not my original plan.”

“But life in Libya is so difficult for us... When I found a job, I wasn’t paid,” Ali continues. “I know that Sudanese people have been kidnapped and tortured. The kidnappers call the families back in Sudan and ask them for ransom... I decided to go to Europe.”

In April 2023, the United Nations published a report documenting the “widespread practice” of arbitrary detention, murder, torture, rape, enslavement and enforced disappearance in the country, saying that there were grounds to believe that “crimes against humanity” were committed against migrants.

Yet since 2017, the European Union has made Libya one of its privileged allies in the fight against immigration. Hundreds of millions of euros have been paid to Libyan authorities, in particular to support the coastguard responsible for intercepting migrants at sea and forcing them back to Libya, where they are imprisoned in detention centres.

In 2023, 17,025 people were intercepted at sea and sent back to Libya. In the same year, more than 2,500 people died or disappeared trying to cross the central Mediterranean Sea, the highest number since 2017.

Ismail’s father was imprisoned, tortured and died in Libya. Ismail also travelled there to try to reach Europe.

“My life was like that of a gazelle running from a lion,” says Ismail. “I tried to reach Europe from Libya and failed. I also failed from Morocco. Then I discovered that a lot of migrants were trying to cross through Tunisia.”

Since 2023, Tunisia has become the main departure country for boats heading for Italy, because of the extreme violence in Libya and the cheaper crossing. In 2023, according to the UNHCR, 84 percent of the Sudanese who crossed the Mediterranean to Italy embarked in Tunisia. In 2022, 98 percent had embarked from Libya.

Following from the border externalisation agreement with Libya, the European Union signed a new £87 million agreement with Tunisia in 2023, aimed at preventing migrants from leaving the country.

However, several organisations have warned of the exclusion and repression of sub-Saharan migrants in Tunisia, including discrimination on the basis of skin colour, family separations, physical and psychological violence, theft and destruction of property, expulsions, arbitrary arrests, forced displacement at the country's borders and disappearances.

Deadly European policies

The European and national policies of countries to curb immigration are abusive and deadly. They add to the economic, social and geographical obstacles, which include crossing the Sahara, the Mediterranean Sea, the Alps and the English Channel.

They force people to take longer and more dangerous routes, which causes thousands of deaths. In recent years, European countries have continued to restrict access to the right of asylum, which is based on principles of solidarity and protection enshrined in international law.

Once they arrive in Europe, people who survive the Mediterranean crossing are faced with asylum application procedures that are often long and complex. The so-called 'Dublin III' regulation prevents asylum seekers from applying for protection in the country of their choice, despite any ties, projects or linguistic and cultural proximity, in favour of the country of entry into the EU.

Added to this are policies which exclude and criminalise migrants, applied by the various European countries through which they pass.

MSF teams are witness to this, particularly in Italy, France, and the UK. In 2019, the psychologists of MSF and another medical organisation supporting migrants in France, named Comede, warned of the toxic consequences of France’s policy of refusing to protect migrants, or the mental health of a large number of unaccompanied minors who are not cared for by child welfare services.

In the space of a year, more than a third of the 180 unaccompanied minors accommodated at MSF’s day centre in Calais have reported being subjected to ill-treatment and violence by the police in France, and especially in Calais.

In Calais, migrants find themselves caught between two countries, France and the United Kingdom, neither of which wish to welcome them. The Touquet agreements of 2004 transferred control of the British border to French soil, with increasing militarisation of the border area, more police, walls, barbed wire fences, surveillance cameras, heat and CO2 detectors to spot people attempting to cross the Channel.

Since the beginning of the year, more than 20 people, including three children, have died trying to reach the UK.

“In France, there’s no help for people like me and it’s complicated to get papers and a job,” says Ali. “I'm sure it’s better to apply for asylum in the UK, where you can get help and find a job more easily... That's what my friends have told me. Whatever the obstacles, the laws or the police, I’ll keep looking for a safe place where I can get a job and a bed to sleep in.”

On the other side of the Channel, since October 2023 MSF in partnership with Médecins du Monde have been running a mobile clinic service providing primary healthcare in a to men seeking asylum who are held in a mass containment centre in Wethersfield, rural Essex.

After six months of medical activities, 74 percent of men who had used our services had serious psychological distress, with 41 percent were experiencing suicidal thoughts, as well as deliberate acts of self-harm and suicide attempts.

“European countries must put an end to the externalisation of our borders,” explains Claudia Lodesani, head of MSF programmes in France and Libya. “They must also increase their refugee resettlement slots via the UNHCR mechanism, as well as other complementary protection channels, including family reunification and work and study visas.”

“It is hypocritical of countries to pretend to facilitate access to asylum on their own soil but prevent access to it over thousands of kilometres”, says Lodesani.

Our teams provide medical assistance to migrants in Belgium, Bulgaria, France, Greece, Italy, Libya, Poland, Serbia, the UK and the central Mediterranean. In 2023, MSF teams carried out more than 77,000 medical consultations and more than 28,300 mental health consultations for migrants whose mental and physical health are directly affected by European policies.

All first names have been changed to protect the anonymity of the individuals concerned.

MSF, refugees and displaced people

MSF works around the world to provide refugees and internally displaced people (IDPs) with the medical care they need, from psychological support to life-saving nutrition.

Our teams conduct rapid needs assessments, establish public health programme priorities, work closely with affected communities, organise and manage health facilities and essential medical supplies, train local workers and coordinate with a complex array of relief organisations.