Surgery in Sudan: “I’ve worked in a lot of war zones... this was my toughest yet”

“On 31 May we had our first mass casualty incident, which is when lots of wounded people arrive at the same time. You never know if it will be 20 or 40 or 100 patients. That day, we had 127 patients…”

Operating theatre nurse Jessica Comi looks back on her “toughest assignment yet” with Médecins Sans Frontières / Doctors Without Borders (MSF), working to treat the wounded caught up in Sudan’s brutal conflict.

There had been an explosion very close to the hospital and very quickly we were inundated with wounded men, women and children. Seventeen people were dead on arrival.

The emergency room (ER) was full, the two operating theatres were full. In one theatre, we were trying to manage the most complex cases; in the second, we were working on cases that were a bit less complicated. That day, we ran the operating theatres until four or five in the morning. We worked non-stop.

I was quite unwell that day, but when you have so many patients needing assistance, you can’t just stop working…

The call. The challenge

My name is Jessica Comi and I’m an operating theatre nurse.

I arrived in Khartoum on 8 May. I’d been working in Syria with MSF’s emergency team when I got the call on a Sunday morning asking me to head to Sudan. I was on a plane that evening.

I was apprehensive, of course. I’ve worked in conflict zones before, but you always wonder if you’ll be able to do the job and if you’ll have a good team. Ultimately, you just have to have faith in your own abilities and trust MSF.

We flew in and the airport was full of people trying to leave the country. I met up with the rest of the team – a surgeon, two anaesthetists and an ER doctor – and we started to get to know each other.

The head of MSF in Sudan and the medical coordinator were already in the country. They’d found a hospital in South Khartoum – Bashair Hospital – which was virtually empty and being run by volunteers. When the conflict started, a lot of the hospital staff had left, so volunteers had stepped in to restart activities. They got in contact with MSF and asked for help.

“I looked around me. It was 46 degrees, we needed water, we needed electricity, we needed medical supplies and equipment… but we did have a surgeon and two anaesthetists”

We arrived at the hospital at around 4 pm and immediately did the rounds. I went straight to the operating theatres. Things were not in a great state. They were out of use, they were missing equipment and supplies, and they needed to be cleaned.

I took a deep breath and asked: “How many hours do I have before the theatres need to be ready?”

“Can you open at midday tomorrow?”

I looked around me. It was 46 degrees, we needed water, we needed electricity, we needed medical supplies and equipment. But we did have a surgeon and two anaesthetists, so we had the capacity to start operating.

So: “Yes, we can do it.”

Why not?

We got to work.

We sorted out the equipment and made sure that what we had was working. With the help of the volunteers, we began to clean. I sourced gowns and sterile equipment. While this was happening, the ER doctor was setting up the emergency room.

The next morning, we talked through the processes with the ER team: working out how they were going to send us patients and how we were going to transfer them back to wards.

The number one priority for us was the safety of our patients – that was the most important thing.

By midday we were ready and the first patients started to arrive. We had 67 patients that day, most of them with gunshot and stab wounds. We worked in the operating theatres until three the following morning and from there on in it never really stopped.

Difficult moments

In those first few weeks, we had some really difficult moments, but we adapted and we improved.

We had no means of communication within the hospital apart from our mobile phones, but we couldn’t always get a signal. So I’d put on a gown and rush out of theatre to confer with the ER.

They started to send beautiful handwritten notes with each patient – a piece of paper with a brief description written in bright blue ink: ‘22-year-old male, gunshot wound in the abdomen, stable.’ As I received each note, I’d attach it to the wall, and that became our surgical list.

Support our expert surgical teams working in crisis zones worldwide

War surgery is complicated. Working with wounded patients brings a lot of challenges and, if you aren’t used to doing this type of surgery, it can be especially difficult.

You need to know the potential risk for a patient if they are not treated immediately – risks such as infections or losing a limb or haemorrhaging.

Bullets and shrapnel are dirty and they create massive wounds, so, in a war zone, you treat every single wound as already contaminated and probably infected. These injuries are complex and you need to act quickly.

But, our team was experienced and that expertise made a big difference.

“That anger motivated us. We needed to rush, we had to do everything we could to save her.”

We saw a lot of patients and many of them have stayed in my mind.

There was an 11-year-old girl called Layla* who had a gunshot wound to her femur, high up in the bone near the pelvis.

You see somebody like her and it just makes you angry: “What is she doing here? She’s just a child, she shouldn’t have to face something like this.”

But that anger motivated us. We needed to rush, we had to do everything we could to save her.

Layla was scared, incredibly scared. But we operated on her and stabilised her, and then, over the following days, we did a series of surgeries and gradually she began to improve.

Understandably she was traumatised, but slowly, over the following weeks, we built up trust and she began to smile and talk.

During her recovery, Layla found it painful to move, so we spent a lot of time sitting with her, listening to her, trying to make her comfortable. Sometimes it’s important to leave all the rush and the emergency for a few minutes to just be with a patient, to spend time with them and listen to them.

Impossible and incredible

We had difficulties getting supplies and it sometimes felt like it was an impossible place to work.

At first, the biggest problem we had was getting enough fuel for the generator so we could have electricity.

The head of MSF in Sudan and the drivers spent a lot of time driving around Khartoum during the fighting trying to source fuel to keep us going. They did an incredible job. They also got hold of medical supplies and equipment for us to use when we were running low.

It was like Christmas for us when they came back with boxes of supplies. We’d open them up and it would be like: “Wow, examination gloves! Disinfectant for instruments!”

We got very excited.

We couldn’t have done the work without the Sudanese volunteers. So many people were coming to the hospital saying: “I don’t want to be paid, I just want to be working alongside MSF for now, because I know this is what my community needs.”

It was incredible.

In the eight weeks I was there, we conducted 525 surgeries on 485 patients. I get goosebumps when I think about that. Working in Sudan, you see how desperate the situation is, but you also see how much of a difference you can make working together as a team.

I have worked a lot in war zones, but this was my toughest assignment yet with MSF.

But it was also very special how the team worked through the challenges together. You could feel that we were all working for one reason – and that was to save lives.

*Name changed to protect identity

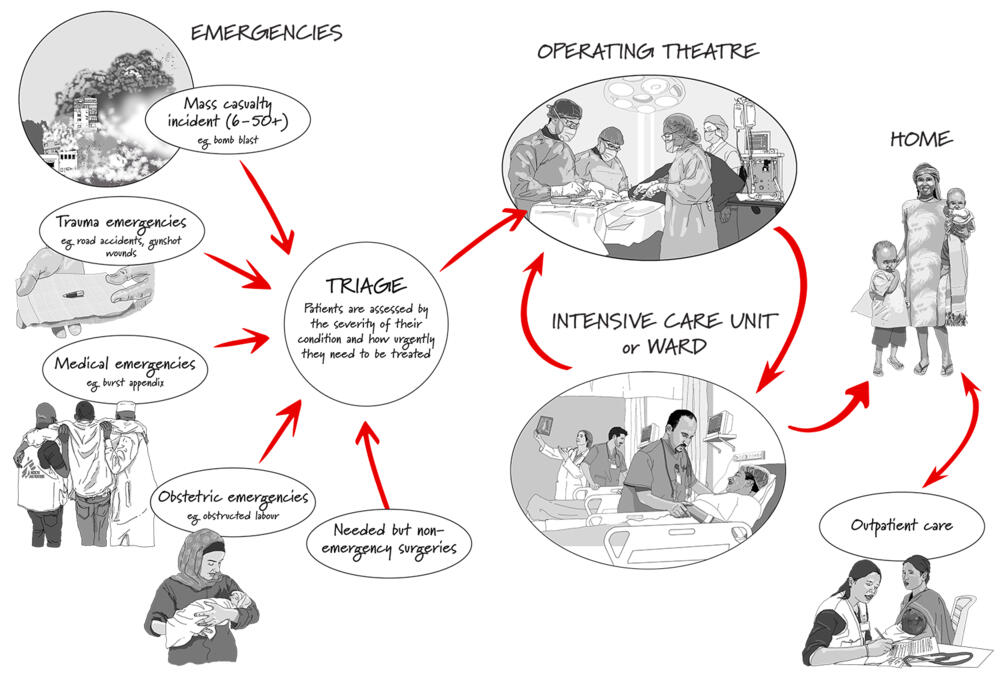

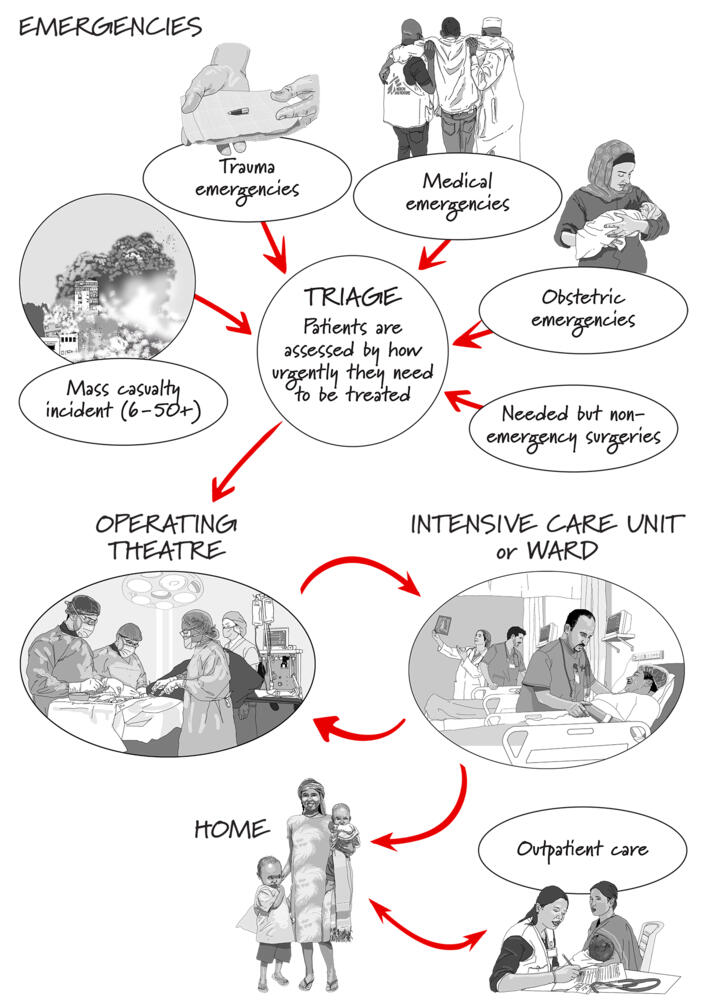

MSF and emergency surgery

Whether it’s a child injured in a bomb blast or a woman with pregnancy complications, emergency surgery saves lives