Voices from Bentiu

A powerful new documentary tells the story of MSF staff and patients living and working inside South Sudan’s massive displacement camp

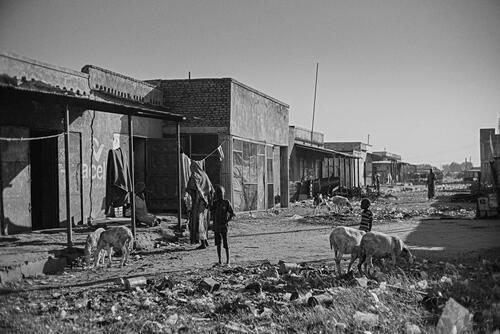

In the north of South Sudan, surrounded by trenches and barbed wire, sits the Bentiu camp. Initially set-up to provide a temporary refuge from conflict, the camp is becoming an increasingly permanent settlement to people who have fled their homes.

Now, a new documentary follows MSF teams inside the camp, working to provide life-saving medical care to those enduring life in the harshest of conditions.

Doctors of War

On Tuesday 20 April, a documentary produced by ITN – “Doctors of War: Saving Lives” – was broadcast at 10 pm on Channel 5 in the UK.

The film follows the work of British surgeon John Buckles, during his assignment with Médecins Sans Frontières / Doctors Without Borders (MSF) in the Bentiu camp.

Warning: the trailer and documentary contain distressing scenes that some viewers may find upsetting

Explained: The crisis in South Sudan

In 2013, less than two years after independence, violence broke out between the South Sudanese government and opposition forces, dragging the world’s youngest country into years of brutal civil war.

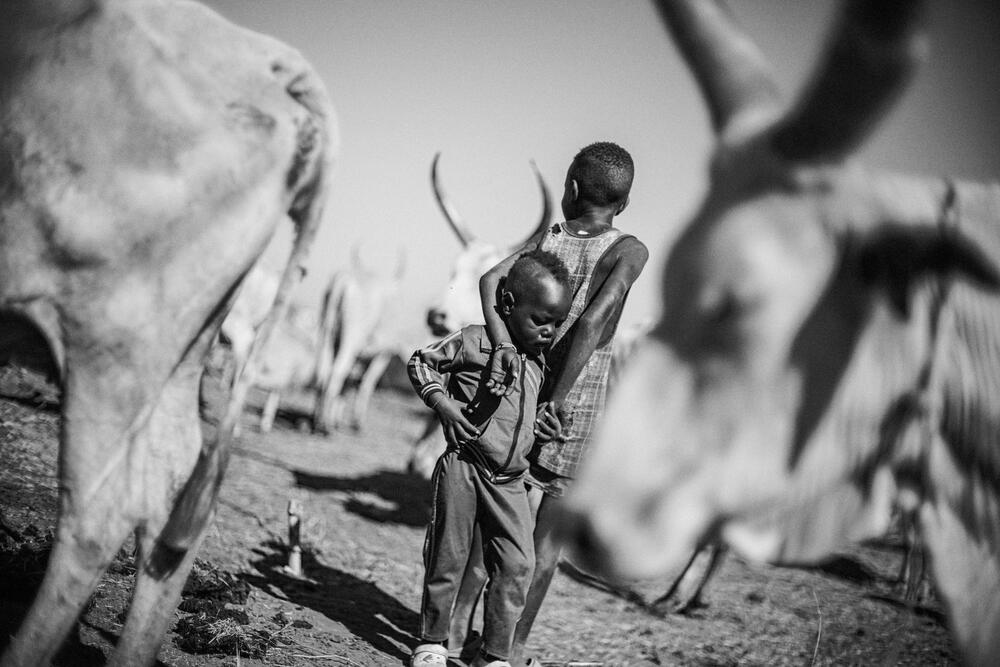

The conflict has claimed approximately 400,000 lives and, combined with the decades of previous conflict before independence, has resulted in over two million people fleeing the country. It has caused the largest refugee crisis in all of Africa – third worldwide behind only Syria and Afghanistan.

Another 1.6 million people remain displaced within South Sudan’s borders.

Bentiu, formerly a camp under the protection of the United Nations, is now an internally displaced persons (IDP) camp under the authority of the South Sudanese government.

These camps – known as Protection of Civilian sites or ‘PoCs’ – were formed around existing UN bases where thousands of people fled for protection during the war. They were never designed to house so many people for such a long period of time.

Four of the five PoC sites across South Sudan have now transitioned from UN protection to being managed by the South Sudanese authorities. Around 170,000 people live in these four camps and the one remaining PoC.

Across the camps, people live mostly in overcrowded shelters made of metal, mud and plastic, offering little protection from the elements, illness or the violence that often strays into the camps.

Bentiu is the largest, home to more than 100,000 people. The poor living conditions and lack of functioning latrines and showers mean there are huge health risks to people living there, including; diarrhoeal disease, hepatitis E, cholera, typhoid and skin infections.

Medical care where it's needed most

Help us care for people caught in the world's worst healthcare crises.

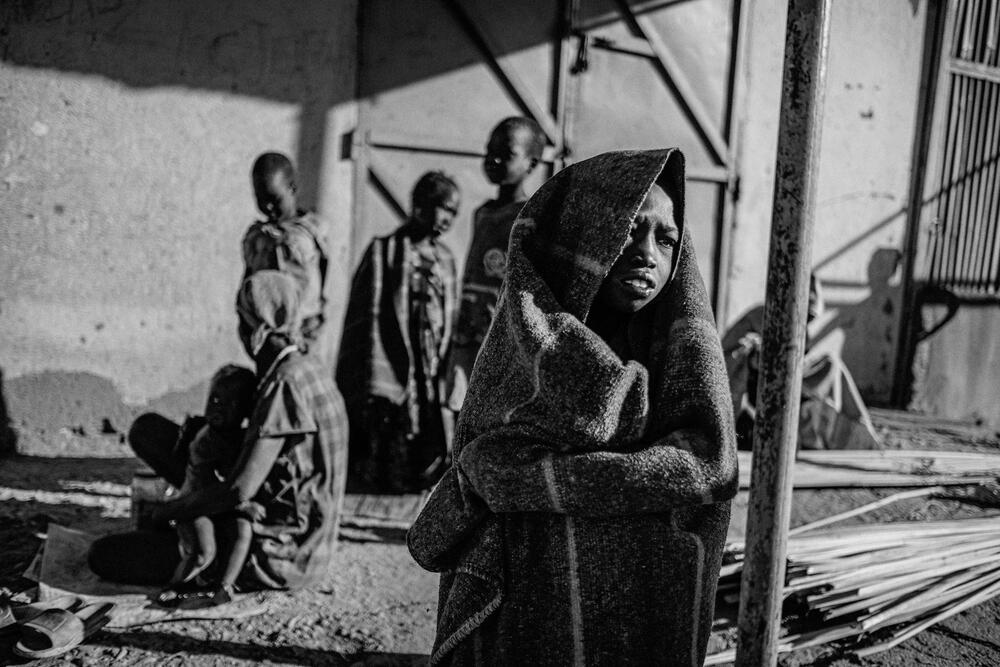

As well as 24 international specialists, the majority of MSF team members in Bentiu (over 500 people) are South Sudanese staff who live and work inside the camp – sharing the same harrowing backstory and day-to-day reality as the people they care for.

Here are three stories from inside the camp, recorded in January 2021 before Bentiu transitioned to government control.

“In the future, we don’t want our children to stay in this place”

Nyanuba Gatwang, sexual violence counsellor

My role is caring for survivors of sexual violence – giving them medication to help prevent them from developing sexually transmitted infections, and providing psychosocial support.

They are suffering from something that was done to them, either on the road while they were travelling or during their daily lives. A lot of children and women are facing a lot of these difficulties with sexual violence – there are a lot of attacks, including rape.

Only a few of them come here to the hospital, most are not reported. This happens both in and outside of the camp. Survivors from the village say they are attacked at night – they are taken out of their homes and forcibly raped.

In the future, we don’t want our children to stay in this place. We are living here now but we are not happy – the situation forced us to live here. We had never lived in a camp like this before.

We don’t want a time like this to happen again. We want to change our lives now so our children don’t have to stay in this difficult life.

“Our hope is that everyone can go home”

Jerome Mamok Keah, midwife

When I was studying midwifery, my plan was that one day I might work with MSF and have a good experience.

My role now is to spot the mothers who are at risk because of their condition and attend to those who need medical care.

In the maternity department I see mothers during outpatient consultations and admit some patients to the ward. For example, if a woman has bleeding, we will keep her in to observe and monitor her condition.

We also help mothers deliver their babies, and if it is a complicated delivery that needs a surgeon, we have a team here that can do that, too.

I like my work here because we can provide a good service to patients. Nothing is missing. If they need medication, I can get them what is needed and hopefully they will be able to go back home.

My own family are not here any longer, so when I am off duty, I cannot spend time with them. Instead, I spend time with my colleagues in the camp – we sit and chat and discuss the future.

We always talk about our own future, in healthcare and studying, and the crisis in this country. We try to brainstorm the situation we have in South Sudan.

Our hope is that this revitalised peace will go well, and everyone can go home and we won’t have to be worried for our families. There will be stability in Unity State. Even some schools here, and everything will be forgotten.

“ I need to see my children. When the crisis in this country is over, I can bring them back.”

Joshua Pekhoa Koang Buom, operating theatre nurse

I’m an “OT” nurse. I’ve been working with MSF for at least 10 years.

However, I was also born in an MSF hospital on 14 February 1990 when my mum was working for MSF as an advisor on HIV and tuberculosis. My father also supervised a therapeutic feeding centre, treating malnourished children.

I grew up, continued my education, then I came back to MSF. My mum is still very strong and working with MSF in Leer [around 100 km south of Bentiu]. MSF even saved my brother when he almost died. Now he is training to be an engineer, but without MSF, I might have lost him.

My role is to take care of whatever procedures happen in the theatres. We have a schedule of patients for the day – apart from the emergencies – and I have a big role when a patient arrives.

I make sure everything is understood by the patient and their family, that we have all the right instruments ready for the surgeon and that everything is sterilised. I assist the surgeon. Often one hand cannot do something alone, but two can do it together. My role is all about communicating very, very well, and I am always learning from the surgeons.

Before COVID-19, you had to have a radio with you when you left work, then if anything happened the surgeon would call you. But now it’s different, and we take shifts staying in the hospital overnight, waiting for anything to happen.

You decide to work for the community with MSF. You have to.

I was born in this country. The only thing I want to happen is to have peace – to have security and work comfortably with my organisation.

Our hope is that one day we can go back to our respective homes… to Leer. Not to stay in the PoC.

I have already sent my children to Uganda as I want to give them a good education. When I have holiday, I try to see them, but sometimes I don’t have good transport and I cannot go.

I need to see my children. When the crisis in this country is over, I can bring them back and we can enjoy everything together.

The future of Bentiu

In July 2020, the UN in South Sudan announced that it would start a process of handing over the five Protection of Civilian sites in the country.

It means the camps will remain, but with management and security responsibilities transferred from the UN to the national government.

As of 19 April 2021, four of the five PoC sites, including Bentiu, had transitioned to internally displaced persons (IDP) camps managed by the government.

Working in Bentiu camp since the camp's formation in 2014, MSF continues to reassure the community that it remains committed to providing much need medical care and humanitarian assistance to the people of Bentiu, irrespective of the camp’s protection status.

After years of protracted conflict and a complex humanitarian emergency, South Sudan's health system is on life support.

Even before the current conflict began, South Sudan had some of the worst health indicators in the world; access to healthcare for only 44 percent of the population and vaccination coverage estimated at just 40 percent. According to the UN, it is estimated that 8.3 million people will require humanitarian assistance this year.

Prior to the recent cuts in overseas aid by the British Government and the merging of the Foreign and Development Office, the UK was the second-largest donor of humanitarian assistance in South Sudan.

How I survived war and displacement in South Sudan

Gatluak works with MSF in Bentiu.

We are deeply concerned about the impact of huge and sudden cuts on an already vulnerable population, like those living in Bentiu camp who, through no fault of their own, are reliant on aid.

Cutting life-saving support through UK Aid cuts will have a catastrophic impact on the health of people in the camp and will almost certainly result in increased mortality and morbidity across the country.

Lives must not be lost due to a sudden lack of funding. Instead, the UK must do all it can to continue to support these vulnerable people.

MSF in South Sudan

In July 2011, South Sudan became the world’s newest country after gaining independence from Sudan. The peace deal that led to the split also ended Africa’s longest-running civil war.

But in December 2013, South Sudan was plunged back into chaos as civil war erupted amid a power struggle between the president and his deputy.

The conflict has forced millions of people from their homes and left many without access to basic necessities, such as food, water and healthcare. Médecins Sans Frontières / Doctors Without Borders (MSF) works in hospitals and clinics throughout South Sudan, where we run some of our biggest programmes worldwide.

As well as providing basic and specialised healthcare, our teams respond to emergencies and disease outbreaks affecting isolated communities, internally displaced people and refugees from Sudan.