Operation Ebola: How MSF's emergency team took on the disease in DRC

Just as we were opening the Ebola isolation unit, a pregnant woman arrived, transferred from another health centre.

Within two minutes of being admitted, she went into labour! The team scrambled to put on protective gear – we had to assume that both mother and baby could be infected…

Less than a year before this day in 2018, I had joined MSF’s emergency response unit – known as the “E-Team”.

I’d always worked in emergency situations with MSF.

Between late 2016 and mid-2017, I was posted to Mosul, Iraq. I was there during almost all of the battle for the city, as Iraqi forces fought the Islamic State group (IS) for control.

That was a huge turning point in my life.

I had gone to Iraq to work on a project where, in terms of potential danger, the security situation was “moderate” but not “high”.

Instead I ended up coordinating a field surgical unit and going into Mosul during these dangerous events.

We built a hospital in the east of the city when it was partially controlled by both IS and the Iraqi army.

It was a very powerful time for me.

I wasn’t sure in what direction I wanted to take my life with MSF, but I knew I needed it to be challenging all the time.

This is how I decided to join the E-Team.

May 2018: Ebola in Équateur

For my first assignment with the E-Team, I was sent to coordinate the vaccination campaign during the Ebola outbreak in Équateur, in the west of the Democratic Republic of Congo (DRC).

It was super amazing. It was May 2018 and the very first time that anyone had ever used the Ebola vaccine at the beginning of an outbreak.

We used a targeted response known as “ring vaccination”.

We needed to be strategic and follow the epidemic, figure out exactly where the hotspots were and vaccinate those who were most at risk.

It was exactly how you would imagine an MSF emergency team works.

We were some of the very first people to arrive on the ground.

Surviving on coffee and cookies

Once we’d touched down in the city of Mbandaka, we took a helicopter out to the remote area that we’d be working in.

It was just us, our bags and some tents under our arms.

We weren’t sure where we would be sleeping, but once we were on the ground we found a derelict house to build our base around.

We put up the tents and got to work.

We had to clean down the house, build a new compound, talk with the community and prepare for the vaccinations.

We had super bad phone signal and no internet, so we had to set up the entire response ourselves. We were so busy.

We were dealing with Ebola, which is contagious and has a high fatality rate.

As we hadn’t yet established all the necessary infection control measures, we didn’t want to risk eating anything bought locally.

All we had was what we brought with us.

So, for the first two days of the emergency, all we ate were cookies and all we drank was Nescafe and water. That was our entire diet.

None of us cared though. We were there to do a job.

I have always thrived in discomfort.

MSF versus Ebola

That was the very beginning of the emergency. We had to define strategies, be creative and be driven by adrenaline.

Soon, we started to see the immediate effect.

Suddenly, we were training people, a lot of people, as temporary staff. And, importantly, within seven days we had started to vaccinate.

Ebola is such a high-profile disease. People have a lot of fear about it.

But when I think about that, I understand that healthcare crises like this are why MSF exists.

All around the world, MSF deals with situations that others don't want to, don't have the capacity to or don’t know the answers to.

Our role is to help find those answers and save lives doing so.

Ebola is scary but we have the training to deal with it.

We have really strong security measures in place, as well as infection prevention and control policies.

Teams responding to Ebola even have shorter assignments so that they don’t get exhausted and make mistakes.

We provide a lot of training and coaching to local and international staff.

I believe that MSF’s rapid response helped control the outbreak, and I left Équateur just a few weeks before it was officially declared over.

But, less than one week later, a new outbreak appeared in the east of the country…

It would become the second-worst Ebola epidemic in history.

August 2018: Epidemic in a conflict zone

When I got the call from headquarters, I had only just arrived home after travelling back to Canada.

Thankfully, I always have a bag that’s never really unpacked. It means I’m always ready to go.

The bag contains everything I might need, from documents and passport photos to a solar-powered battery pack, and even a very important vegetable peeler!

I immediately flew back to DRC.

This time the outbreak started in North Kivu, a region of DRC that has long suffered insecurity and instability.

It would be the first ever time that an Ebola outbreak had been declared inside an active conflict zone.

This outbreak continues today. To date, it has killed more than 2,200 people.

At different times in this outbreak, I have been the emergency coordinator for MSF, looking after the practical side of the response.

I have also led the medical team when needed.

It’s a fascinating job. I have to be strategic, manage the security situation, assess what’s happening and figure out what we really need to be doing.

Gaining trust

As well as the outbreak happening in an area where there is armed conflict, there is also quite a limited healthcare system.

Many people don’t have access to basic needs, such as clean water.

With the arrival of Ebola came a lot of suspicion and mistrust about the disease and the people who came to respond to it.

There were all sorts of rumours and the community was understandably resistant to outsiders coming in without asking what their own priorities might be.

The situation is complex.

In one place where we worked, there had been about 40 cases of Ebola in three weeks.

However, the community didn’t identify this disease as their main priority – the lack of access to water and basic healthcare had been hitting their community hard for a much longer time.

That was what was most important to them. So, that’s what we did first.

Then, eventually, the community asked us for help with Ebola and we built an isolation unit for potentially infected patients.

We set up triage and infection prevention controls. We worked with the community and trained them in the basics of biosecurity.

We even asked them to help us design how they wanted the isolation unit to look, what materials did they want to use?

It was super different from what we had done in the past. One particular unit looked like a nice chalet.

It was all about gaining trust and addressing the needs of the community.

A dangerous birth

In places where there is Ebola, people often stop going to healthcare facilities at all because of the fear of either getting Ebola or being identified as a suspected case.

In one village, we built a new Ebola isolation unit at a health centre. However, very few people were coming to the health centre.

Then came the day of the inauguration…

Just as we were celebrating the opening of the unit, a pregnant woman arrived, transferred from another health centre. Within two minutes of being admitted, she went into labour!

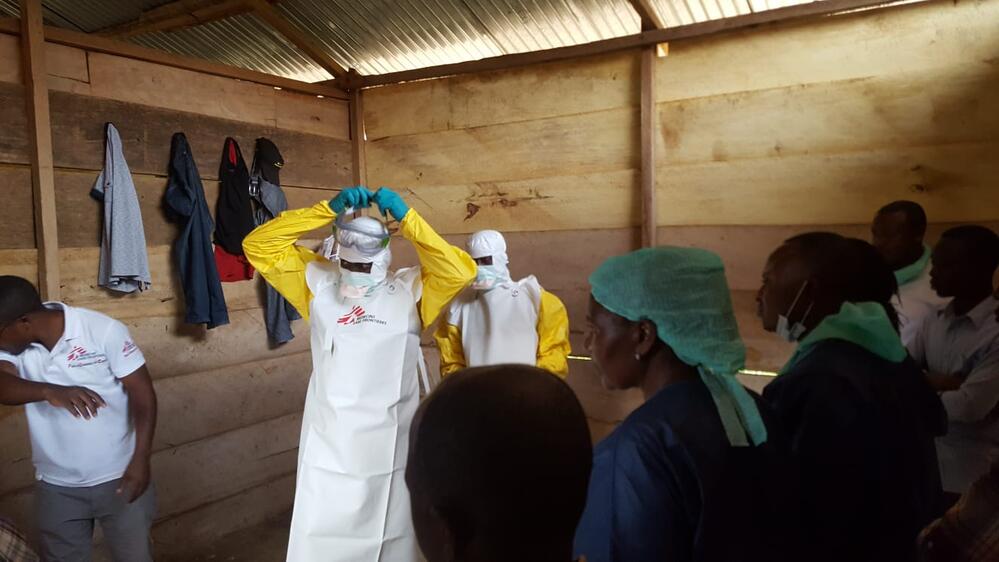

The team scrambled to put on protective gear. We had to assume that both mother and baby could be infected.

It was a critical situation – everyone in the community was waiting to see what would happen.

Sadly, Ebola often causes women to miscarry or give birth prematurely. Working in an Ebola isolation unit, you see pregnant women die or have miscarriages.

You can imagine what this was like for our team.

We had brilliant local staff, but they had only just been trained in dealing with Ebola and now had to help their first potentially infected patient give birth! All while wearing the thick protective Ebola suits.

Thankfully, the woman and her baby survived the birth. We took really great care of them while they remained in the isolation unit.

And, when we received the news that their test results for Ebola were negative, it was even more reason to celebrate!

Overcoming the fear

The very next week, after the mother and her new baby went home, we held our weekly prenatal clinic at the health centre.

The week before, absolutely nobody had showed up – perhaps for fear of Ebola. But that morning, 89 women arrived for consultations!

They had heard that this woman had given birth safely, inside an Ebola isolation unit.

That she had lived and her child had lived. That neither of them had Ebola.

Seeing all the mothers arrive for this potentially life-saving care was such a great feeling.

We had overcome the fear.