Malnutrition in Massakory: The late shift

So far this year, over 650 acutely malnourished children have been treated in the inpatient centre run by the MSF team in Chad's Massakory Health District. Nurse supervisor Soldongar Ngaro shares the story of just one shift...

My name is Soldongar Ngaro, I am a state registered nurse from Chad, and part of the team at MSF's nutrition project in Massakory, where I am responsible for our inpatient therapeutic feeding programme.

Our hospital

Massakory is located in the west of the country, approximately 150 km from the capital N'Djamena. Malnutrition is a persistent problem here. Our patients are facing a lack of clean drinking water, nutritious foods, and difficulties accessing health care. All of these things can lead to malnutrition.

My patients are young: children under five years old. They all suffer from malnutrition and other medical complications. Not all hospitals with a dedicated nutrition department accept malnourished babies under six months, but we do. Their care needs are different, but we have the specialised skills and supplies.

"A while ago, I was with some friends when a woman approached me. I didn't recognise her, but she recognised me. She explained to me that I had helped care for her child when he was very ill. She said her little boy is now home with the family, having made a full recovery."

Intensive care

The day before yesterday, I had a very difficult shift in intensive care.

My shift started at 4:30 p.m. Our intensive care unit has five beds, and this is where we take care of the most seriously ill children.

At the start of the shift it was clear that there were three children on the unit who were particularly ill, including one baby only a few months old.

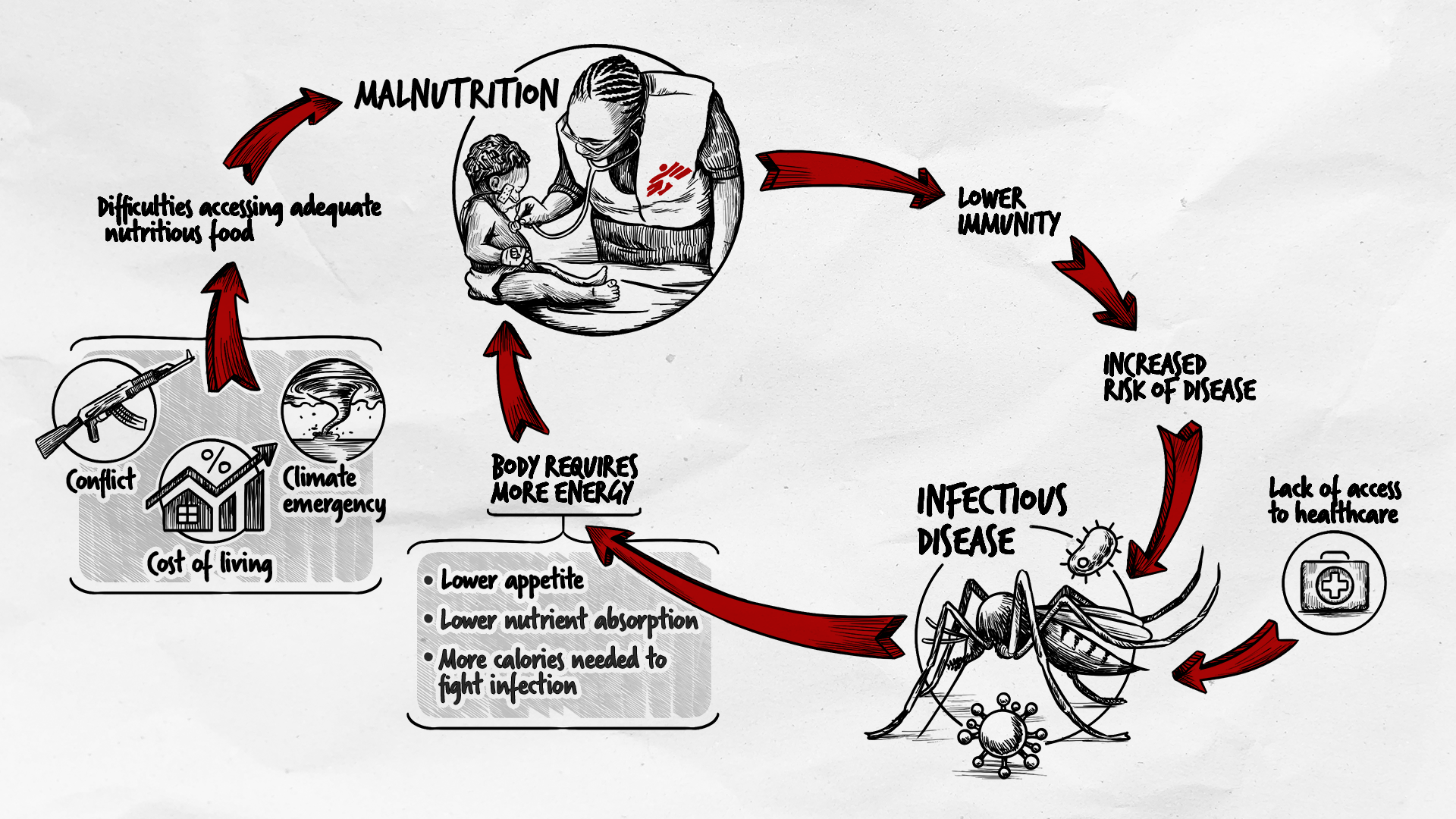

Sometimes people think that treating malnourished children is just about food. But when children are malnourished, their immune systems are weakened and the body cannot cope with infections that would not be a problem for well-nourished children. An infection that causes vomiting or diarrhea can quickly become dangerous, and when our mobile clinic team regularly finds children in the community who need urgent hospitalisation.

Struggling to breathe

That day in intensive care, we had three children who were in very precarious conditions. These were patients who had respiratory infections, others with anaemia, others with sepsis complicated by metabolic disorder (hypoglycemia), which meant they had difficulty breathing. We were giving them oxygen therapy, but with the infection causing blockage in their lungs, it was difficult to know if that would be enough.

Doctors had prescribed the relevant medications, but as night fell, the temperature of all three of these patients remained stubbornly high.

£24 could pay for a week of therapeutic food for three malnourished patients

The generosity of people like you means expert MSF medical teams can deliver essential medical care to people across the world.

The three ways to leave

There are only three ways for a child to leave ICU.

Our goal is that with treatment they stabilise and require less intensive care, so we are able to transfer them to the inpatient department.

The second way a child can leave the intensive care unit is if a parent takes them home against medical advice. We work hard to counsel parents and prevent this from happening. However when a child has been hospitalised for a long time there can be pressures at home that mean families must take difficult decisions, and may decide to rely on traditional medicine instead.

The final way a child leaves the intensive care unit is that, despite our best efforts, we are unable to save their life. The children we see in intensive care often suffer from severe malnutrition, with multiple medical complications.

At 11 pm, I finally sat down to do the medical notes for the shift. There are three ways to leave intensive care, and each of the three children I was caring for that night took a different one.

Comfort and support

As a medical team, we are here to help people, but sometimes God decides otherwise. It is part of the job, but it is essential that we remain professional and try to offer support or comfort to the grieving family.

By the time I left work that evening, I was exhausted. But I am proud to do this work and to work for MSF. We cannot save every patient admitted to our hospital, but the community here knows that we will always do our best for them.

When you ask someone in the villages where we work, they tell you that "Yes, MSF comes here, they offer care and therapeutic food, and if our children are sick, MSF sends them to the hospital and then brings them back." This trust is essential.

Our impact

A while ago, I was with some friends when a woman approached me. I didn't recognise her, but she recognised me. She explained to me that I had helped care for her child when he was very ill.

She said her little boy is now home with the family, having made a full recovery.

It is very rare for a Muslim woman in this region to approach someone on the street like this, so her determination to share her thanks has stayed with me.

Medicine is not divine. We make all our efforts to provide good care and to have the supplies and materials we need in place. And sometimes that's enough.

MSF and malnutrition

Around 45 percent of all deaths in young children are linked to malnutrition; when children suffer from acute malnutrition, their immune systems are so impaired that the risk of death is greatly increased.

In 2022, we admitted 127,400 severely malnourished children into inpatient feeding programmes (an increase of 55% on 2021) across the world, and 324,591 to outpatient programmes (an increase of 100% on 2021).