Long-read: The babies born after the Battle of Mosul

It is a rainy morning in the Al-Nahwaran neighbourhood of Iraq’s second city, Mosul, and a group of women are lining up in front of a small medical centre.

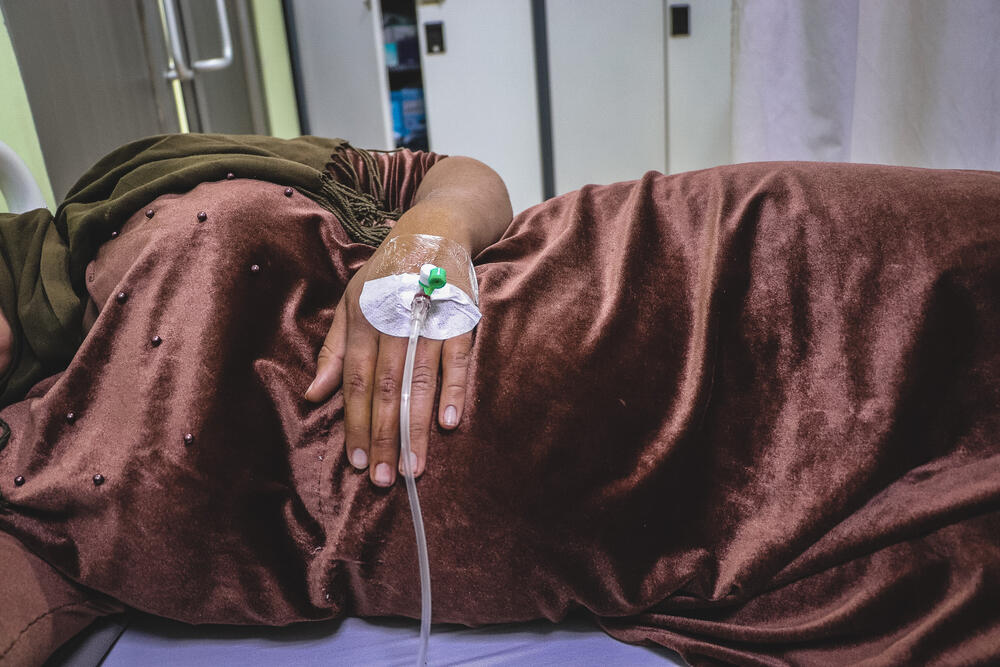

The stormy weather has not stopped them from coming. The bellies of some of the women speak of the reason for their visit.

Maram, a young woman from Mosul, is standing in front of the maternity unit’s ambulance, patiently waiting for her turn to enter the building. The 20-year-old is three months pregnant, expecting her third child. She has come for her first antenatal check-up.

“I came here because my relatives told me about this maternity unit,” she says.

“My sister-in-law came here before, and she recommended it.”

Word travels fast in Mosul and beyond, and more and more women have been coming here for maternity services in recent months.

“Most hospitals and health facilities are still currently being rebuilt or renovated [after the conflict]. But look at these women expecting babies – they simply cannot wait for these renovations to be completed."

Located on the west bank of the Tigris River, MSF’s Al-Amal Maternity Centre offers routine obstetric care, newborn care, health promotion services, family planning and mental health support.

“We first opened this maternity unit because there were significant needs in the city when it came to access to healthcare in general, and even more so in the field of sexual and reproductive healthcare,” says Yousif Loay Khudur, MSF’s assistant project coordinator.

“Three years later, many women still need to come here because the city’s health system is far from functional.”

War is over but recovery takes years

In June 2014, Mosul fell under the control of the Islamic State group.

Then, in October 2016, a military offensive led by an alliance of the Iraqi security forces and an international coalition was launched to retake the city.

The following battle for Mosul stretched over 250 days and was described as some of the deadliest urban combat since World War II.

In July 2017, Mosul was officially declared retaken by Iraqi authorities. But, five years later, many medical facilities damaged in the fighting are yet to be fully renovated and made fit for use, while there are still shortages of medical supplies.

As a result, thousands of families in and around Mosul still struggle to access quality affordable healthcare. Among the most vulnerable are pregnant women and their babies.

“Before 2014, Mosul’s health system in the city wasn’t perfect, but it was functional,” says Yousif.

Help us prepare for the next emergency

“Women used to deliver at home or in one of the city’s hospitals. But during the military operations in 2016 to 2017, a lot of medical facilities were damaged or destroyed and their equipment was stolen.

“The rehabilitation of medical facilities in the city took a long time to start and, even though it’s been almost five years since the battle of Mosul ended, we still very much feel the after-effects of it today. Most hospitals and health facilities are still currently being rebuilt or renovated. But look at these women expecting babies – they simply cannot wait for these renovations to be completed.”

In response to the high level of unmet needs after the battle for Mosul, MSF opened a specialist maternity unit in Nablus hospital in West Mosul in 2017 to provide safe, high-quality and free maternal and neonatal care for women and their babies.

In July 2019, a second MSF team opened the Al-Amal maternity unit within Al-Rafadain primary healthcare centre, also in West Mosul.

Last year, MSF teams in these two facilities assisted in the births of almost 15,000 babies.

Physical and mental health

Rafida, aged 15, recently gave birth to her first child in the Al-Amal maternity unit after hearing about the facility from neighbours and relatives. Holding her son Layth in her arms, she says she is grateful for the care she has received.

No fewer than 35 midwives and midwife supervisors work in the facility day and night, seven days a week, to assist women in delivering their babies.

“On average, we assist between 10 and 15 deliveries on a regular day, but it can go up to 20 to 25 deliveries on a busy day,” says Rahma Adla Abdallah, a midwife supervisor.

“But unfortunately, we still can’t cover all the needs. We help most women, but we have to have admission criteria to maintain the best possible level of care within the limits of our own resources.”

Along with her colleagues, Rahma tries to help as many women as she can. The midwives not only assist with deliveries but also provide antenatal and postnatal care and family planning services, which draw many women from all over the city.

“I hope the future will get brighter and brighter. I hope I’ll bring other children into the world too. And if I do have other children in the future, I’ll come back here.”

Another key service is mental health assistance.

“Women in this community not only need access to physical healthcare; they also need full mental health support,” says Rahma.

“Gender-based violence is an issue we sometimes witness, for instance. Some of our patients have experienced it but they very rarely talk about it.”

Iraq’s Directorate of Health has also set up dedicated health services in the city to provide care for survivors of gender-based violence.

“But there is still a long way to go before proper access to both physical and mental healthcare can be guaranteed in Mosul,” says Rahma.

Maternal healthcare for all

The stigma around issues such as gender-based violence is just one of the many barriers to healthcare in Mosul, but the lack of access to sexual and reproductive health services in the city has various causes.

“The environment is particularly complicated here,” says Bashaer Aziz, another midwife supervisor working in the Al-Amal maternity unit.

“A significant number of women cannot access healthcare," continues Bashaer.

"Either because they do not have the means to pay for it, or because they face other challenges, such as not having official administrative documents, due to the recent conflict or being displaced from their homes.

“So, when patients come to our facility, they are generally very grateful to receive good medical and obstetric care. They don’t have other places to go; they cannot afford to pay for services at hospitals or private clinics.

“Our maternity unit makes a big difference to them.”

In numbers: Our work on maternal health

369,000

BIRTHS ASSISTED BY MSF TEAMS IN 2024, INCLUDING CAESAREAN SECTIONS

94%

OF ALL MATERNAL DEATHS OCCUR IN LOW AND LOWER MIDDLE-INCOME COUNTRIES

700

WOMEN DIED EVERY DAY FROM PREVENTABLE CAUSES RELATED TO PREGNANCY AND BIRTH IN 2023

Finding a place to give birth safely is just one of many challenges faced by Mosul’s expectant mothers, including sometimes how to properly feed themselves and their children.

“Sometimes women arrive here, and they have not eaten anything,” says Rahma.

“Sometimes it’s impossible to tell how far along they are in their pregnancy. Sometimes they come with their kids, who are very thin or underweight. So, our work here is to offer an alternative for them and to try to help as much as possible with the services we can provide.”

Both Rahma and Bashaer agree that MSF’s maternity unit plays a positive role in the neighbourhood.

Mahaya, 50, who has accompanied her daughter-in-law to the unit to give birth, feels the same way. They have come from Tel Afar, more than an hour away.

“Before this maternity unit existed, nothing was available and we used to deliver at home,” she says.

“A midwife would come, deliver the baby, and that would be it. There wasn’t even a hospital we could go to. This maternity unit is a big improvement in our lives.”

At the end of her shift, Rahma likes to spend time in the maternity unit’s postnatal ward.

She takes into her arms one of the babies born that day, a little girl named Rivan. Although she is just a few hours old, her eyes are already wide open. The baby gazes at her mother, 19-year-old Bouchra, who is recovering in a bed beside her.

“The birth was difficult, but all went well, and the midwives helped a lot,” she says.

“Rivan is my first child and I feel happy to have her. I hope the future will get brighter and brighter. I hope I’ll bring other children into the world too. And if I do have other children in the future, I’ll come back here,” she says with a smile.

MSF and maternal health

Many women across the world give birth without medical assistance. This massively increases the risk of complications or death. Ninety-nine percent of these deaths are in low-income countries, and the majority are preventable with appropriate care.

Our healthcare teams work together with pregnant women to provide delivery services, emergency obstetric care and post-delivery consultations.