A new chapter of hope for hepatitis C patients in Rohingya refugee camps

Viral hepatitis is a global health crisis, claiming over 1.3 million lives every year. In Rohingya refugee camps in Cox's Bazar overcrowded conditions and limited access to healthcare have created a perfect storm for its spread.

A recent MSF study indicates a shocking reality: nearly 20 percent of people tested in these camps have an active hepatitis C infection. Dr Farhana Yesmin explains how MSF's 'test and treat' campaign is changing lives.

“I’ve been working on the hepatitis C project at Hospital on The Hill (HoH) since March 2025. Every day, I see first-hand the silent struggle of so many, a struggle that often goes unnoticed until it's too late. But I also see immense hope, fuelled by the dedication of our teams and the incredible resilience of our patients.

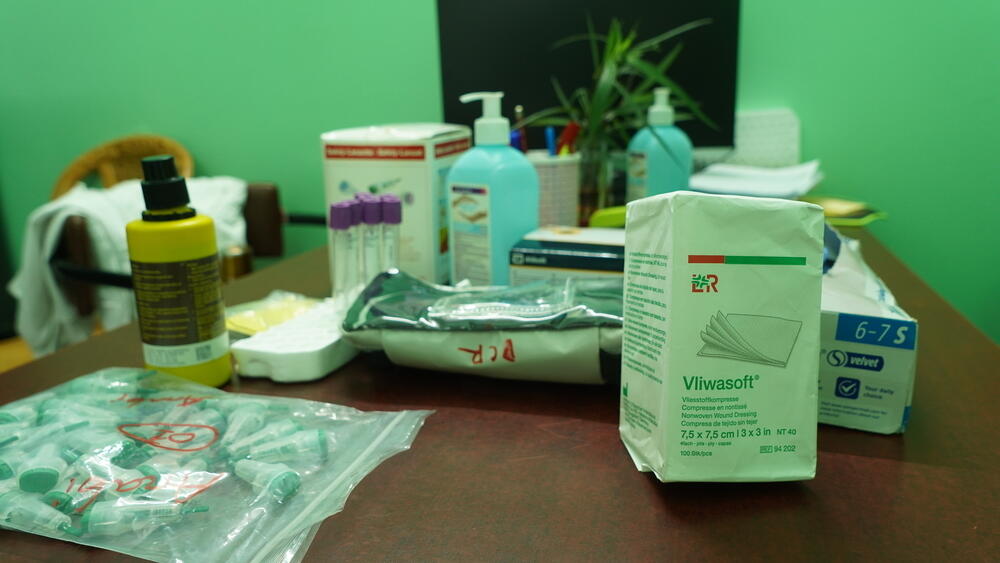

Here at HoH, our focus is on providing comprehensive treatment for hepatitis C and addressing its related complications. We're on the front lines of a major health challenge. The rate of hepatitis C infection in these camps is alarmingly high, which is precisely why MSF launched our intensive "test and treat" campaign.

The numbers tell a stark story. So far, we've screened nearly 12,000 people out of our target of just over 12,700. The positivity rate stands at a concerning 19 percent, meaning we've identified 2,136 individuals who are positive for hepatitis C.

We've already started treatment for 2,102 of them. It's a massive undertaking, but each person treated is a life changed.

Help us prepare for the next emergency

We've observed that many people simply don't know they have hepatitis C because it often shows no symptoms for years. When we deliver a new diagnosis, it can be a shock, but it also opens the door to life-saving treatment. The more we test, the more we find, and the more lives we can save.

Working in this context, we definitely face a unique set of challenges. We encounter patients who, in addition to hepatitis C, are co-infected with other serious conditions like hepatitis B, HIV, or tuberculosis.

When we refer them for follow-up testing for these conditions—whether it's in three or six months—they can understandably become distressed about not receiving immediate treatment for all their ailments. It’s a challenge to manage their expectations and reassure them that comprehensive care is coming.

What is hepatitis C?

The disease is described as a "silent killer" because, in many cases, it presents with no obvious signs or symptoms. People can be infected for years, even decades, without knowing it. Sometimes, there might be very mild, flu-like symptoms such as a slight fever, nausea, or vomiting, but often, nothing at all.

This insidious nature means that over time, the virus gradually damages the liver, leading to severe conditions like cirrhosis or even liver cancer. Because symptoms don't appear early, many people don't seek testing or treatment until it's too late.

For those diagnosed with hepatitis C, there’s a general sense of relief and happiness that treatment is finally available for a disease that previously had no local solution. In our clinic, we provide one-on-one counselling to ensure they feel comfortable and can speak freely.

Families are often very supportive; if one member tests positive, they are often keen to bring other family members, including children aged 11-17, for testing. This willingness to seek testing as a family unit is a positive step towards broader prevention.

A significant improvement in our service has been the change in age restrictions for treatment. Previously, we couldn't treat anyone under 40, which meant many younger individuals, like the wives of positive patients, were left without care.

Now, we're able to treat patients from 11 years old and above, significantly expanding our reach and ensuring more people get the life-saving medication they need.

MSF in Bangladesh

It's over seven years since hundreds of thousands of Rohingya arrived in Bangladesh, fleeing persecution in Myanmar, yet the possibility of a safe return remains remote. Dire, overcrowded living conditions, a lack of basic services and a complete reliance on humanitarian aid are taking a toll on both refugees and the host community.

Médecins Sans Frontières / Doctors Without Borders (MSF) provides medical services through multiple health facilities in Bangladesh, primarily serving Rohingya refugees and host communities in Cox’s Bazar and the capital, Dhaka.