The unseen cancer that’s killing women

In 2018, an estimated 311,000 women, including over 1,000 in the UK, died of cervical cancer.

Cervical cancer is preventable and curable.

So why are women still dying?

On International Women's Day, we're sharing the truth about this silent killer – and how our teams are fighting back.

Here are seven things you should know about cervical cancer.

1. Cervical cancer is caused by a virus

Nearly all cases of cervical cancer can be attributed to the human papillomavirus, or "HPV", one of the most common sexually transmitted infections, which affects both men and women.

In many women, the infection will spontaneously clear.

But for others, over time, chronic infection causes abnormal changes in the cells of the cervix, the entrance of the womb.

If left untreated, these changes can progress to cancer over a period of 15 to 20 years.

HPV infection is especially aggressive in HIV-positive women and girls, which means they can develop cervical cancer in less than half that time.

2. It can be the deadliest cancer for women

In 2018, more than 85 percent of the women who died from cervical cancer lived in low- and middle-income countries.

In 42 countries around the world it kills more women than any other cancer. Compare that to the UK, where cervical cancer ranks 18th.

The inequality of this disease is stark.

MSF has its most comprehensive cervical cancer programme in Malawi, which has the world's highest mortality rate and the second highest rate of new cases.

But access to treatment isn't the only reason women in poorer countries are hardest hit...

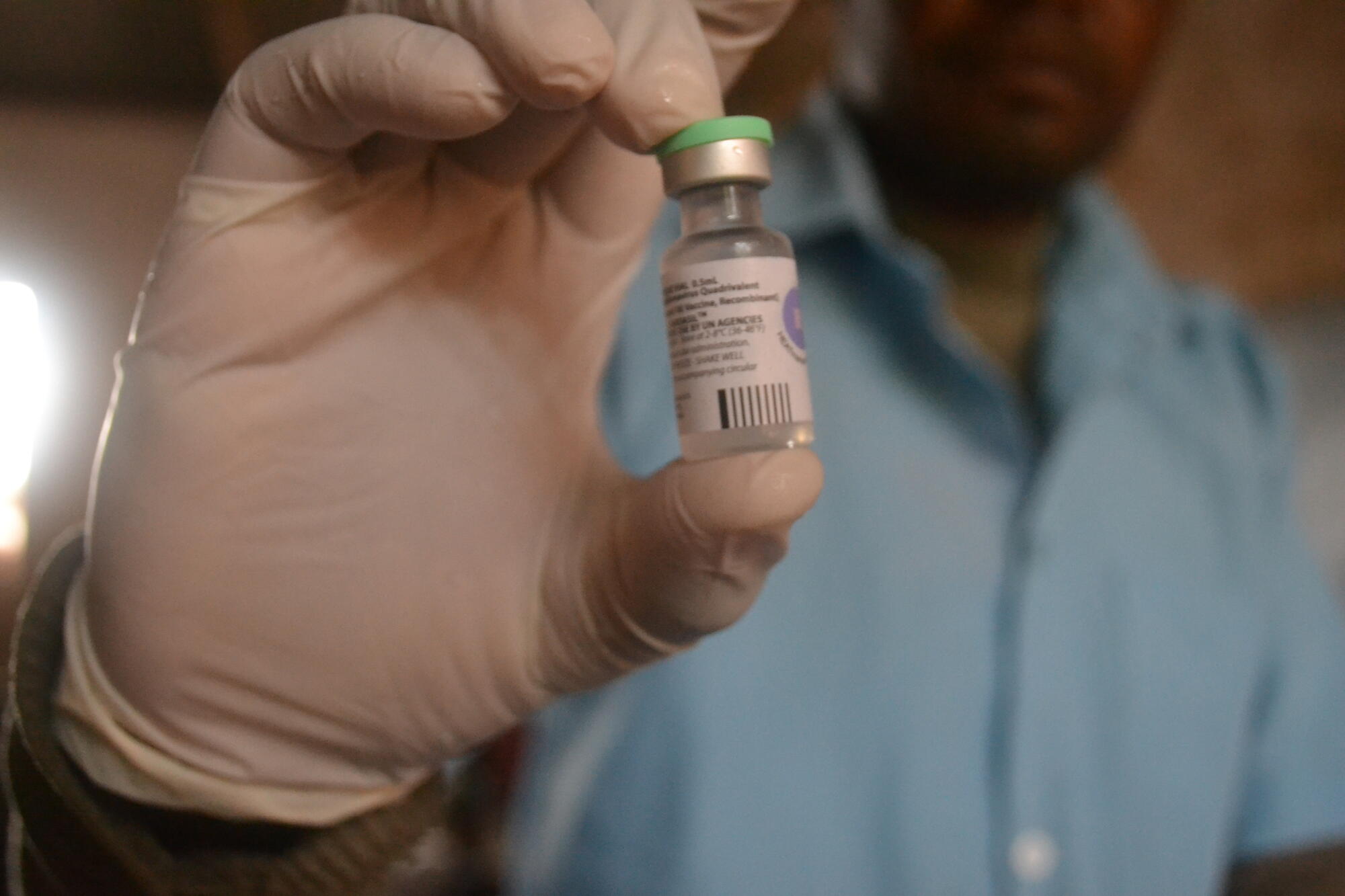

3. A simple vaccine could wipe out cervical cancer

Prevention of cervical cancer should start before girls are exposed to HPV.

The World Health Organization recommends vaccinating against the virus between the ages of nine and 14.

In the UK, girls and boys aged 12 to 13 are offered two doses of the the HPV vaccine at school.

350,000

CERVICAL CANCER DEATHS WORLDWIDE IN 2022

90 %

OF CERVICAL CANCER DEATHS OCCUR IN LOW AND MIDDLE-INCOME COUNTRIES

8,500

GIRLS VACCINATED AGAINST HPV BY MSF TEAMS IN MALAWI BY JANUARY 2023

Since the first vaccine’s introduction in 2006, countries that have been able to introduce vaccination programmes, like the UK, have seen impressive results.

There are now confident predictions that cervical cancer will be eliminated in high-income countries in the near future.

But in other parts of the world, where the HPV vaccine is less readily available, it’s a different story.

4. Screening saves lives

While an effective vaccine exists, many women grew up before it was introduced and many young girls still don’t receive it.

In poorer countries, “screen and treat” programmes make it possible for healthcare providers to identify, destroy or remove pre-cancer – all in one visit.

The relatively simple infrastructure and equipment needed for screen and treat makes it a cost-effective strategy in places where sophisticated analytics are out of reach due to expense, distance, or the complex resources needed to support them.

In 2018, MSF doubled its screen-and-treat coverage, screening over 20,000 women in five countries.

5. Big pharma is putting profits over women's lives

Pharmaceutical company Merck produces two of three current HPV vaccines, dominating sales.

But, as unprecedented demand drives a global vaccine shortage, Merck is failing to meet the needs of the countries hardest hit by cervical cancer.

Merck is prioritising higher-paying customers, such as those in European and North American markets, by expanding production of the more expensive version.

As a result, the life-saving vaccines remain unaffordable and unavailable in many countries, with governments forced to leave millions of girls unprotected.

Because of this critical shortage, we are also limited in any additional vaccination efforts we might provide.

6. There is hope: our teams work in the worst-affected countries

We run cervical cancer projects in Zimbabwe, Mali, Malawi and the Philippines, and recently handed over our activities in Eswatini to the Ministry of Health.

Our teams work in collaboration with local health authorities and non-government organisations to provide services ranging from health promotion and training to surgery and palliative care.

Our screen and treat programmes mean women such as Shuvai Munyaradzi (below) are able to take control of their health and go on to lead long, happy lives.

Shuvai lives in Gutu town, Zimbabwe, where MSF supports the local hospital. After hearing about cervical cancer screening, she booked a consultation during which the nurse detected some abnormalities on her cervix.

Shuvai was concerned about the result but with her husband's support and counselling from hospital and MSF staff, she underwent cryotherapy.

The day after her screening results came back clear, Shuvai discovered she was pregnant with her third child.

In January 2020, she gave birth to a little girl, who she named Chidochashe – "will of God" – in honour of her successful treatment.

7. More must be done to end preventable deaths from cervical cancer

Huge advances in cervical cancer prevention and treatment have been made in high-income countries, yet poorer countries are being left behind.

It is unacceptable that a woman’s likelihood of dying from cervical cancer depends largely on where she lives.

Without an increase in vaccination, screening and treatment, the death toll will continue to mount. To end preventable deaths:

- Big pharma must make the HPV vaccine more affordable, and increase production, so that every girl is protected;

- Screen and treat programmes must be integrated into health services, everywhere, and incorporate newer, more sensitive methods, such as HPV screening, to detect affected women earlier;

- Cancer treatment must be urgently expanded. With mortality still so high, chemotherapy, radiotherapy and surgery need to be accessible for women diagnosed early enough. Psychological and social support cannot be overlooked.

Please help us raise awareness about cervical cancer by sharing this with your friends and family on International Women’s Day.