South Sudan: 150,000 people cut off from care as MSF forced to close hospital

Escalating insecurity has forced the closure of MSF’s Ulang Hospital, which will have devastating effects on the local people’s access to healthcare.

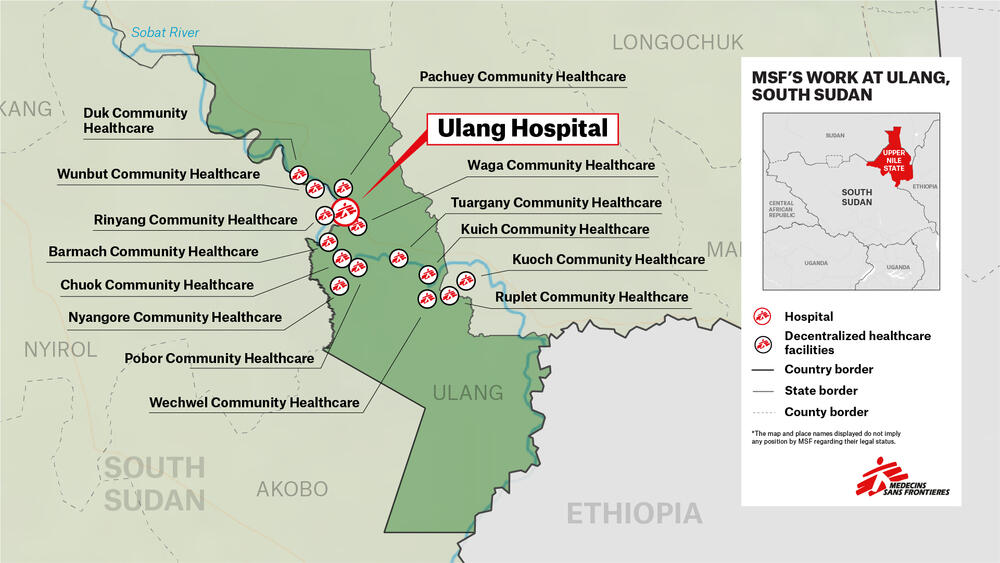

Attacks on medical boats and armed looting in medical facilities since the beginning of the year have forced Médecins Sans Frontières / Doctors Without Borders (MSF) to close its hospital and end its support to 13 community-based primary healthcare facilities in Ulang county.

This has left hundreds of thousands of people in remote areas of Upper Nile State in South Sudan without access to healthcare. Without MSF’s hospital, an area of more than 120 miles from the Ethiopian border to Malakal town is left without any functional secondary level healthcare facility.

MSF calls on all parties to adhere to international humanitarian law, cease such indiscriminate attacks, and ensure the protection of medical facilities, health workers, and patients.

Sign our petition demanding the protection of healthcare

Despite these closures, MSF remains dedicated to supporting the healthcare needs of displaced and vulnerable people in Ulang and Nasir counties.

Help us prepare for the next emergency

A mobile emergency team is assessing the needs and is prepared to provide short-term healthcare services wherever security conditions and access allow. MSF is continuing to provide healthcare services in its other projects in Upper Nile State, including in Malakal and Renk Counties.

What’s happening in South Sudan?

Since February 2025, South Sudan is experiencing its worst spike in violence since the 2018 peace deal. Fighting between government forces and armed youth militias has escalated across multiple states, including Upper Nile, Jonglei, Unity, and Central Equatoria. This has led to mass displacement, widespread civilian casualties, and a total collapse of already fragile public services.

An escalating trend of violence against healthcare

In January 2025, MSF faced an attack by unidentified gunmen on its staff near Nasir, shooting at their boats as they returned from delivering medical supplies to Nasir County Hospital. This attack forced MSF to suspend all its outreach activities in Nasir and Ulang counties, which included medical referrals by boat along the Sobat River that allowed women to deliver their babies safely.

In April 2025, armed individuals forced their way into the hospital in Ulang where they threatened staff and patients and looted the hospital so extensively that MSF no longer had the necessary resources to continue operations safely and effectively.

“They took everything: medical equipment, laptops, patients’ beds and mattresses from the wards, and approximately nine months' worth of medical supplies, including two planeloads of surgical kits and drugs delivered just the week before. Whatever they could not carry, they destroyed,” says Zakaria Mwatia, MSF head of mission for South Sudan.

Within a month, another MSF hospital was bombed in Old Fangak, a town in the neighbouring Jonglei state, leaving the facility completely non-functional. This is part of a worrying rise in attacks on healthcare facilities in South Sudan.

Getting mothers to hospital by boat ambulance

“During my third pregnancy, I decided to come to the hospital well in advance before my delivery. I lost my two first children because I did not make it to the hospital on time,” says Nyapual Jok, a young mother from the outskirts of Ulang county.

Nyapual had been transported to the hospital by one of MSF’s boat ambulances, since she lives in a remote village far away from Ulang Hospital.

Ulang, a vast flood-prone area, is dotted with remote villages which often suffer severe mobility restrictions during the rainy seasons. MSF ran boat transportation services to ensure access to healthcare to mothers like Nyapual.

“It’s very hard to access healthcare here. If we had a hospital closer during my previous deliveries, maybe my children would be alive today,” adds Nyapual.

Nyapual shared her story in November 2024, only two months before the attack on the same boats which helped her deliver her baby safely.

Gaps that are difficult to fill

The attacks’ effect of stopping medical referrals by boat has had fatal consequences for the people living in remote areas in the region. People in Ulang and Nasir counties had to wait for days, sometimes even weeks, to get a boat to take them to Ulang Hospital.

In desperate situations, they would walk for days through a muddy landscape – a land that is nearly impossible to cross on foot during rainy season.

“We need a hospital nearby that can help mothers and children. Without it, many will suffer and lose their lives.”

Veronica Nyakuoth, an MSF midwife at the Ulang Hospital, shares the story of a patient she attended to at the maternity ward:

“She was in labour when she suffered birth complications – she had to get to a hospital as soon as possible.

Normally, MSF mobile teams would have been able to pick her up by boat, but since that service was cut off, instead she had to wait two days for a private boat to take her.

When she finally made it to the hospital, it was too late: the team could not find a heartbeat from the twins she was carrying in her womb.”

150,000 people cut off from care

With the closure of the hospital and the withdrawal of support to the decentralised facilities including transportation of patients, more than 150,000 patients, including mothers such as Nyapual, will now face even more difficulties accessing healthcare in Ulang county, and more might face the tragic fate that Veronica’s patient had to suffer.

Over 800 patients with chronic illnesses such as HIV, tuberculosis, and others have lost access to treatment due to the closure of MSF services in the area.

Nyapual’s heartfelt plea resonates deeply: “We need a hospital nearby that can help mothers and children. Without it, many will suffer and lose their lives.”

Her story, along with those of many others, serves as a stark reminder that healthcare is a fundamental right and should never be a target. The consequences of attacks to healthcare are more than the damage to a building; it’s the loss of hope, safety, and the chance for a healthier future.

MSF in Ulang

Since 2018, MSF had been providing vital health services in Ulang including trauma, maternal and paediatric care. The teams also supported 13 facilities to offer primary healthcare services.

Over the past seven years, MSF teams carried out more than 139,730 outpatient consultations, admitted 19,350 patients, treated 32,966 cases of malaria, and assisted 2,685 maternal deliveries, among other essential services.

During this time, MSF also provided support to Nasir County Hospital and responded to multiple emergencies and disease outbreaks.

MSF in South Sudan

Médecins Sans Frontières/Doctors Without Borders (MSF) works in hospitals and clinics throughout South Sudan, where we run some of our biggest programmes worldwide.

As well as providing basic and specialised healthcare, our teams respond to emergencies and disease outbreaks affecting isolated communities, internally displaced people and refugees from Sudan.