Imprisoned, exploited, abused: the horrifying reality for people trapped in Libya

In 2017, horrifying images of people being sold as slaves in Libya were broadcast around the world, sparking a global outcry.

Many countries, including the UK, promised measures to protect refugees and migrants from abuse and slavery-like conditions.

But two years later, nothing has really changed and human beings continue to be traded like cargo, passing from trafficker to trafficker.

MSF teams have been caring for migrants and refugees in Libya since 2017.

We have witnessed the desperate situation of thousands of people, condemned to languish in detention centres or left to survive alone outside, trapped in an endless cycle of violence.

How we got here

For decades, oil-rich Libya has attracted people from neighbouring Niger and other sub-Saharan countries hoping to work in construction, agriculture and the services industry.

Since the 2011 uprising, the fall of Colonel Gaddafi and the civil war that followed, the situation for migrants working in Libya has become far more difficult.

The country is riven with armed conflict and as rival governments and militias fight for control, public services have collapsed.

The majority of migrants do not have residence permits or other documentation, which puts them at risk of arrest and arbitrary detention.

Whether they see Libya as a stop on their journey or their destination, all become targets on migratory routes made more dangerous, costly and fragmented.

Moussa's story

"I am 26 years old and originally from Kayes in Mali. After leaving my hometown, I went to the capital Bamako in the hope of finding work, without success.

I then moved to Algeria, where for a year I worked as a welder in the Adrar region before continuing to cross the Sahara, a really dangerous road.

I was afraid of being taken prisoner or killed. When I eventually arrived in Libya, my bag and papers were stolen at the border and I was sent to the Tajoura detention centre in Tripoli. I managed to get out because my family paid 2,500 dinars for my release.

For two years, I have been living within the four walls of the garage I work in, constantly afraid of being arrested and sent back to prison. I cannot take the risk of moving because I am undocumented."

How European policies are facilitating abuse in Libya

While Colonel Gaddafi was in power, the EU and Italy both struck contentious deals with Libya, providing funding in return for a promise to keep migrants and refugees away from Europe.

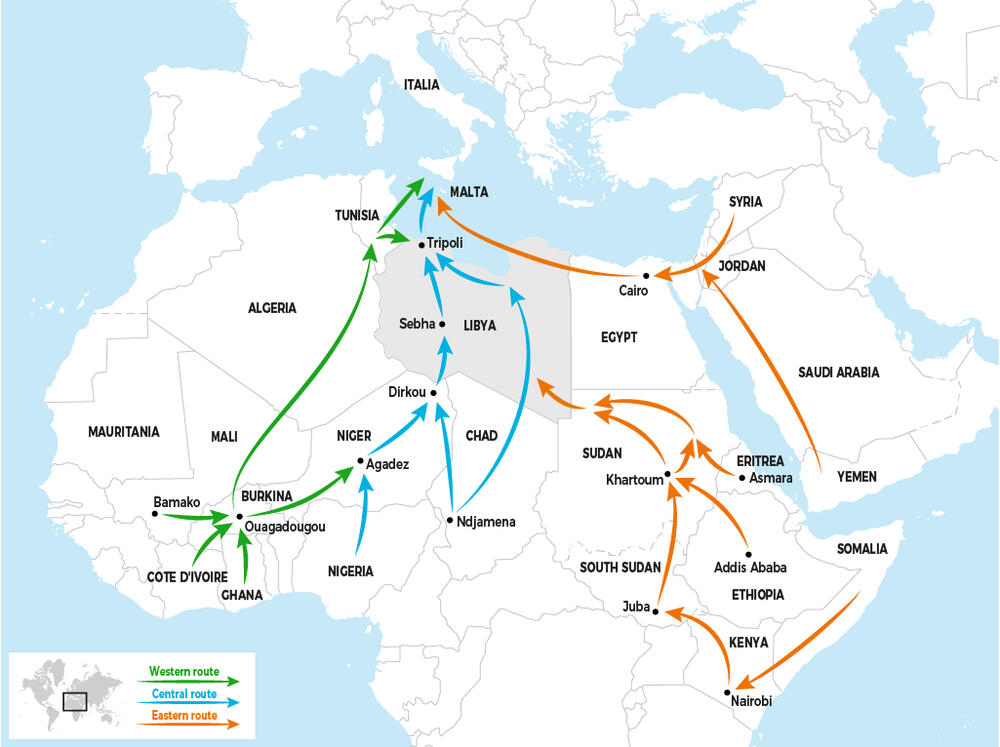

Libya has turned into the major gateway to Europe for those fleeing repression, conflict and poverty in the region.

They have dismantled life-saving search and rescue capacities at sea, while sponsoring the Libyan coastguard to intercept refugees and migrants in international waters and forcibly return them to Libya, in violation of international law.

All this while cutting deals with organisations known for their links with criminal and smuggling networks.

As a result, human trafficking, abduction, detention and extortion of migrants and refugees have flourished in Libya, while people’s chances of dying in a bid to cross from Libya to Europe have only increased.

Why current measures aren't working

The mechanism for evacuating refugees from Libya to transit countries currently operates at a snail's pace: the lengthy procedures use restrictive criteria and there is a real lack of resettlement spaces provided by safe countries.

In contrast to these very limited evacuations, the European state-sponsored system of forced return to Libya is working at full capacity.

From January to November 2019, 2,142 refugees were evacuated out of Libya by the UN Refugee Agency, UNHCR.

By comparison, nearly 9,000 people were forcibly returned there after attempting to flee by sea.

I was in prison for six months. The moment I entered, four men threw me to the floor. They beat on my back until my back broke.

Even escalating armed conflict in Libya has not changed Europe's policy of forced return and containment.

Now, refugees and migrants are not only being detained for an indefinite period and without trial, but they are directly in the firing line.

On 3 July, 2019, an airstrike on the Tajoura detention centre in the eastern suburbs of Tripoli killed 53 people trapped inside and injured 130.

This tragedy was entirely preventable and occurred after numerous MSF calls for immediate evacuation of migrants and refugees caught in the conflict.

Why we don't know exactly how many people are affected

There are between 3,000 and 5,000 migrants and refugees held in "official" detention centres in Libya. The majority of these are registered with UNHCR and are seeking asylum.

An unknown number of people are being held captive across the country in clandestine prisons and warehouses by smugglers and traffickers, who use torture and abuse to extort money from them.

The conditions in the warehouses and other buildings where traffickers hold migrants and refugees are appalling.

In some, hundreds of people are held in darkness, unable to move or eat properly for several months and subjected to the worst abuses to extort more money from them.

MSF does not have access to these prisons, but we treat some of those who manage to get out after paying their ransom, escaping or being released by jailers who no longer expect to get anything more from them.

In Bani Walid, we are able to care for the survivors of the clandestine prisons still active in the area.

We have seen the scarred and broken bodies and heard stories of burning plastic poured on skin, daily beatings, and torture inflicted during a phone call to the victims' relatives to convince them to pay.

This continued to happen on a large scale in Libya in 2019.

Meskya is one such survivor and shares her story.

In recent months, detention centres have been closing or releasing their prisoners.

In some cases, refugees and migrants brought back by the EU-supported Libyan coastguard are no longer sent into detention.

But where can they go? Who can they turn to? How can they avoid kidnapping, forced labour and other dangers?

Hundreds of millions of euros have been spent on assistance and protection programmes for migrants and refugees in Libya since 2017.

Yet, on the ground, operational deployment did not follow and the negotiation capacities of organisations such as UNHCR with the Libyan authorities remained very weak.

After surviving the horror of clandestine prisons or official detention centres, survivors have no place to shelter, even temporarily.

The situation at sea

In September, MSF resumed its search and rescue activities in the Central Mediterranean.

Over the last four months, the Ocean Viking has rescued 1,030 people.

Tragically, almost 700 others are known to have died or gone missing in the Central Mediterranean in 2019.

These are just the people we know about.

In 2019, it is estimated that for every 18 people who reached Europe, one died attempting the crossing.

There is an urgent need for dedicated search and rescue capacity in the Mediterranean.

What Niger has to do with it

People in Libya live under conditions of war and the continuous threat of arbitrary detention, torture, rape, sexual exploitation and other human rights violations.

Among those who are not in detention centres or victims of human trafficking, many strive to leave the country.

Some try to find their way out via the Mediterranean Sea, while others risk their lives going south into Niger.

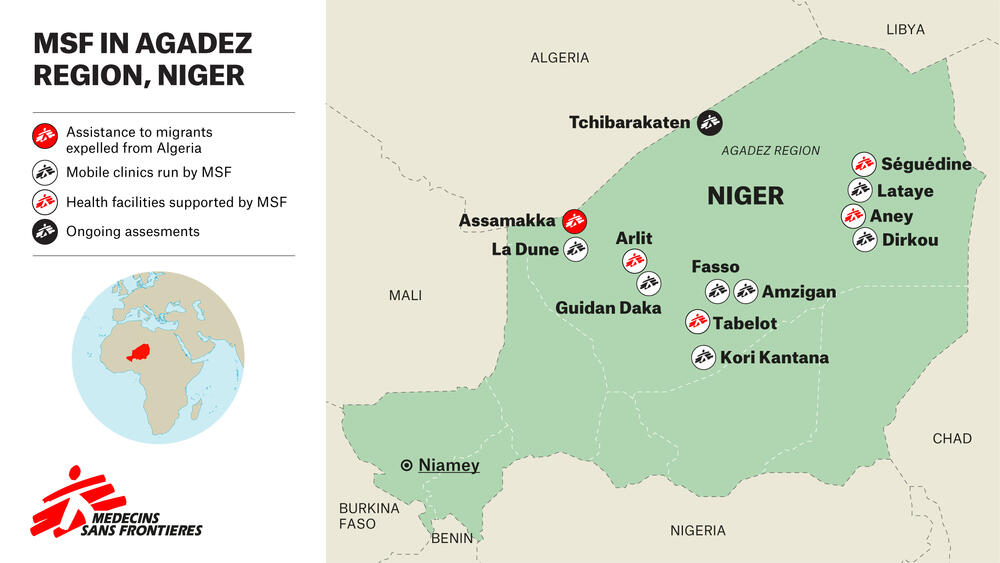

In Niger, our teams in the central region of Agadez have encountered many of these survivors. Some are stranded in the desert of the Ténéré region in northeastern Niger or seeking healthcare in the medical facilities we are supporting.

Agadez is a crossroads, where migrants and refugees coming from Libya are joined by thousands of others who cross the Sahara desert looking for work, returning home or simply in search of a safe and dignified future.

In recent years, these have included tens of thousands of people rounded up and expelled from Algeria.

Between January and October 2019, migration flows across Niger doubled compared to the same period last year; from an estimated 266,590 in 2018 to more than 540,000 this year.

The number of people who died during those journeys remains unknown.

Taken from detention, dropped in the desert

The migrants, refugees and asylum seekers expelled from Algeria arrive in Niger on foot, with nothing but the clothes they are wearing, often exhausted and disorientated.

They have usually been picked up off the streets in Algeria and put into detention centres, where minimum standards of living conditions, judicial guarantees and protection are allegedly not being granted.

Later they are dropped at "Point Zero", close to the border with Niger, from where they have to walk around 15 kilometres to reach the Nigerien village of Assamaka.

Young, old, pregnant – the Algerian authorities do not discriminate.

Dozens of people expelled from Algeria have reportedly been subjected to violence during their deportation process, including instances of rape.

As our teams are only able to take a small number of testimonies due to time and access constraints, this likely represents a small fraction of the total number of people who are abused during expulsions.

The majority of people expelled from Algeria try to re-enter within 24 hours using smugglers operating in the area. At the same time, some Syrians, Bangladeshis and Yemenis get forcibly sent back to Algeria by Nigerien authorities.

This has occurred on multiple occasions since the beginning of the year, with asylum-seekers among them, and raises concerns about violations of international refugee law.

What MSF is doing to help

MSF has been helping people on the move and vulnerable host communities in the Agadez region of Niger since August 2018.

We do this by providing healthcare in existing medical facilities, through mobile clinics in transit locations and in ‘ghettos’ or ‘maisons closes’ (where people engage in sex work).

In addition, our teams identify and refer those in need to be assisted by organisations specialising in protection concerns.

We also recently started search and rescue activities in the Ténéré desert, which is part of the Sahara.

Despite harsh weather conditions, people continue to attempt to cross the endless dunes, perilous routes and their limited means making them extremely vulnerable.

Some don’t make it.

Piles of stones in the sand often mark the tomb of those who have died, buried by the survivors.

We are supporting teams composed of staff from the Ministry of Public Health, desert guides and members of the local Agadez community.

Since July 2019, teams have rescued over 40 people and we have provided urgent assistance to 30 more.

How we can end the cycle of detainment and violence

Europe and the UK are pushing vulnerable men, women and children into the grips of exploitation by denying them a safe or legal alternative.

For many people, their only chance of reaching safety is contingent on risking their lives on dangerous journeys.

They are left at the mercy of criminals who run the smuggling routes, or risk being caught and arbitrarily detained.

First-hand accounts collected by MSF over recent months reveal terrible ordeals.

Warning: some viewers may find this video distressing.

There is an urgent need for humanitarian aid to be deployed more widely and transparently to migrants and refugees in Libya and Niger.

The arbitrary detention of migrants and refugees must stop immediately.

Containment in places where people’s basic rights cannot be guaranteed is not a humane solution to prevent people from reaching European shores.

Instead, shelters where people can be assured of safety and assistance must be set up as a matter of urgency, while their evacuation can be organised.

But this can only work if the UK and Europe:

- Stop returning people to Libya who have tried to escape by sea

- Provide dedicated search and rescue in the Mediterranean

- Increase their resettlement commitments, including humanitarian evacuation.

We owe it to our fellow human beings.

MSF in Libya

Since the end of the Muammar Gaddafi regime in 2011, Libya has been divided by armed conflict and the violence has escalated in recent years.

Médecins Sans Frontières/Doctors Without Borders (MSF) first began working in Libya in 2011, when the country was plunged into chaos after fighting between rival factions forced people to flee their homes. In 2019, the renewed conflict brought more suffering to the people of Libya, and particularly to the hundreds of thousands of refugees and migrants trapped there.

We have treated people arbitrarily detained in official centres, those who have escaped from clandestine prisons run by traffickers, and people who have been intercepted trying to escape Libya by sea.