How AI helps identify snakebites

What's bitten me? Dr Gabriel Alcoba explains an app which uses AI that makes it easier to identify snake species and decide on the correct treatment for snakebite.

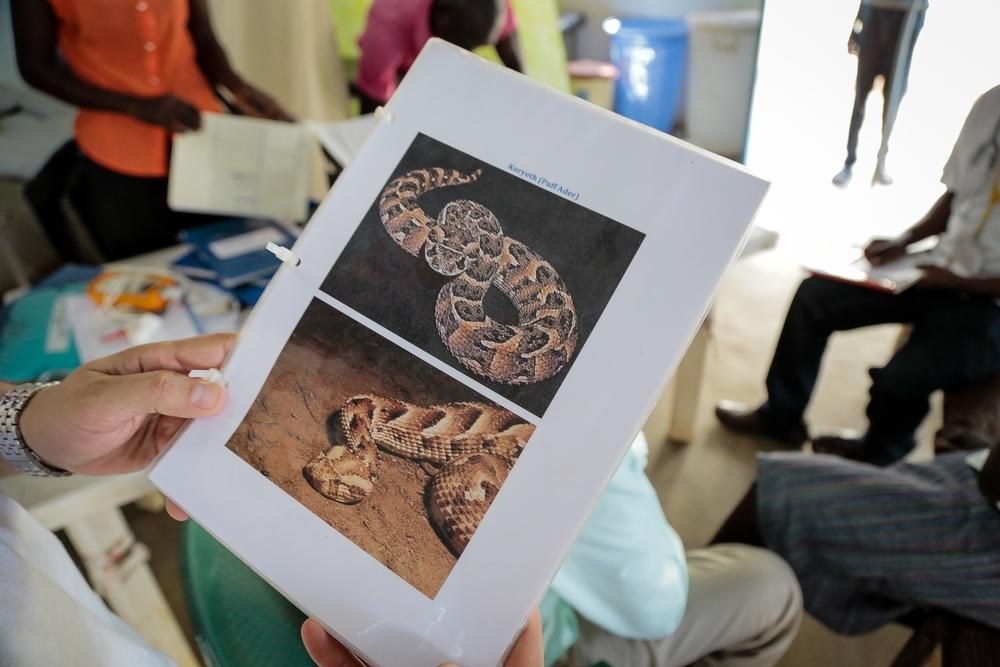

I remember a time when we used photo albums to identify snakes in the Médecins Sans Frontières / Doctors Without Borders (MSF) hospitals. The medical staff would flick through the pictures to find out which snake had bitten a patient.

There are now faster and more reliable methods that use the latest technologies: artificial intelligence and machine learning.

Experts from the University of Geneva and MSF have created a database with around 380,000 photos of snakes from various countries and are constantly developing it further.

The associated app uses artificial intelligence to make it easier to identify snake species and thus provides essential information for the right treatment.

The app can accurately identify around 20 snake species, and most of the approximately 500 cases of snakebite that we treat in South Sudan, for example, are caused by these snake species.

Help us prepare for the next emergency

What is snakebite?

The World Health Organization (WHO) estimates that 5.4 million people are bitten by snakes, with 1.8 to 2.7 million cases of envenomation.

Around 137,880 people die each year as a result of snakebites, and around three times as many people lose limbs or suffer other permanent disabilities as a result of a snakebite.

Innovation in action

In South Sudan, we are currently trialing the identification of snakes using AI in two of our hospitals - in the towns of Twic and Abyei. The initial results are promising: the AI sometimes identifies snakes even better than experts!

My colleague Noon Makor, head of the health promotion team in Abyei, reports:

“The use of the app in the project not only helps to identify snakes, but also makes it easier for the medical team to decide on the treatment of patients.

“For example, it can distinguish between venomous snakes such as the Egyptian cobra or the black mamba and harmless snakes such as the African house snake. This helps enormously to reduce the waste of valuable antivenoms.”

Patients often receive the wrong treatment because the snake has not been correctly identified, or valuable antivenom is wasted on bites from non-venomous snakes, which can also cause serious side effects.

South Sudan has one of the lowest numbers of ecological studies on snakes, but also a high number of snake bites. Between May and October in particular, we admit many people to our hospitals with poisoning from snake bites.

Last year, we treated 481 people in the two hospitals in Twic and Abyei due to a poisonous snakebite.

Part of the project is also to provide information about snakebites, for which the team promotes their message through radio ads and at information events for the affected communities. They also organise interdisciplinary workshops for health personnel.

“This improves knowledge about ecology, mapping and the diversity of snake species in the villages around Twic and the hospital in Abyei, and people learn how to react quickly and correctly to a snakebite,” says Noon Makor.

“We can see this, for example, in the fact that more people are coming to us for treatment of a snakebite. The long distance to hospitals is still a challenge - you really need to be treated very quickly after such a bite and if the nearest hospital is too far away and you don't have transport, it can be difficult - but compared to previous years, we are still seeing an improvement.

“People know more about what to do and that and where they can seek treatment. So our work is having an effect. There is also a kind of ambassador effect: the patients we treat return to their communities and report and actively contribute to improving knowledge about snakebites and getting people treated in time.”

Challenge 1: Recognising the snake correctly

In order for the AI to identify a specific snake, we need a photo of the snake that has bitten the patient. In reality, it looks like this: the person who has been bitten or someone nearby tries to take a photo of the snake with extreme caution.

If this is not possible, our staff sometimes go back to the site of the bite and try to find and photograph the snake.

Once we have a photo, it is uploaded to the app, which compares it with thousands of images to identify the snake. At the same time, the image is added to the database as a new entry with GPS coordinates.

We are currently working on collecting high-quality photos to feed into this software. With better quality photos, funding and further research, this snake AI app could help treat patients faster and correctly - it could save limbs and lives.

The non-profit SNAICS (Snakebite Awareness and AI Identification in Communities) project, together with the AI Snake app, aims to improve our understanding of the different snake species and optimise the supply of antivenom to ensure effective clinical responses.

Challenge 2: Having the right antivenom at hand

Identifying the snake is an incredibly important step, but it is not the only challenge we face in the treatment of snakebites.

Although millions of people worldwide are affected by snakebites, very little research is being done into antivenoms and too few affordable antivenoms are being produced. In South Sudan, for example, a dose of antivenom can cost a patient between a month and a year's salary.

This is why the WHO classifies snakebite envenomation as a so-called neglected tropical disease.

People in remote, rural or flooded areas and in conflict zones in low- and middle-income countries are particularly affected by snakebites. There is therefore no lucrative market for medical products.

Biomedical research and development must be orientated towards health needs, not profit potential: more financial resources and political commitment are needed to combat neglected tropical diseases.

The development of new antidotes and the further development of innovative approaches such as the identification of snakes using AI are just one of many examples.

MSF and snakebite

MSF is campaigning to improve access to more effective and affordable antivenom – a major barrier to improving survival rates.

We cared for 6,747 people who suffered snakebites in 2023.