Haiti: How one hospital adapted to a tumultuous year

This year has been a dramatic one for Haiti.

The capital, Port-au-Prince, is in a state of high tension as armed groups vie for power across the city and challenge the government. An economic and political crisis has worsened since mid-2018, and violence and insecurity are widespread.

The assassination of the president in July only underlined the instability of the situation. Then, in August, the country faced one of the worst natural disasters since the 2010 earthquake.

Nicolas Broca was the head nurse at Médecins Sans Frontières / Doctors Without Borders' (MSF) trauma and burns hospital in Tabarre, Port-au-Prince, from August to November. He describes how hospital staff responded to the challenges.

"In Haiti, the context is constantly changing. One of the things that struck me during my time in the country is that there's always something that you don't expect. You have to adapt constantly.

Three days after I arrived, the 14 August earthquake struck southern Haiti. The capital was not directly affected, but our Tabarre hospital soon filled with patients from the south.

These were people with complex injuries from the earthquake. Some reached our hospital three or four days late because of transportation problems following the earthquake, and their wounds had become infected.

Some had even developed antibiotic-resistant infections, which are particularly difficult to treat.

Complex wounds

In the week after the earthquake, the level of violence in Port-au-Prince was much lower than usual, as the city's various armed groups let people move more freely.

Help us prepare for the next emergency

But by the following week, a high level of violence resumed in the city, and we started to receive as many wounded people as we usually do, while our hospital was already full of earthquake survivors.

As head nurse, I was managing the supervisors of nurses, nurse aides and hygienists in each hospital unit.

The hospital includes the only specialised ward for patients with severe burns in Haiti, which MSF relocated from the Cité Soleil neighbourhood earlier this year because of armed clashes there.

Caring for burns patients requires a great number of staff because their health is very fragile. You have to have someone monitoring their vital signs constantly, and the smallest problem can become a very big problem for a person's body.

The patients need a lot of protein and other nutrients to help them heal, and they need to compensate for the loss of fluids. There is also a huge demand on the staff to provide clean linens and sterilise medical instruments, because of the patients' repeated dressing changes and vulnerability to infections.

In addition, there is a big need for mental health workers to help patients face the challenges.

Political crisis

Staffing the hospital became more difficult when transportation was shut down in Port-au-Prince.

Political tensions, strikes and a fuel shortage prevented hundreds of staff members from commuting to work as they normally do.

The city was completely blocked, and even though strikers allowed MSF vehicles to pass through their demonstrations, it was very stressful for staff members to be out in this environment.

Our logistics team told us they were struggling to obtain more fuel for our vehicles and generators, and we had only a 15-day supply at the hospital, so we had to do everything we could to limit our consumption while maintaining vital medical services.

Our staff all started working 24-hour shifts, to reduce everyone's movement in vehicles. We reduced the number of administrative and logistical staff, and at one point we reduced our criteria for admission, accepting only patients who would not survive if they were referred elsewhere.

However, people continued to arrive in grave conditions, and there was generally nowhere else to refer patients with severe burns.

In times of fuel shortages, people would stockpile fuel at home in unsafe containers, such as plastic bottles, and this led to accidental burns. Sometimes an armed group would attack people by setting their houses on fire.

You don't hear a lot about COVID-19 in Haiti, but it creates challenges too. We test all new patients, and we have a very strict limit on people visiting the hospital to limit COVID-19 transmission, but we must still allow children to have a family member present, for example.

This creates risks for patients and staff. When a staff member tests positive, they must stay home, and when a patient tests positive, they must be housed in a separate area of the hospital and given oxygen therapy if needed. So far, we have not seen COVID-19 deaths among our patients there, fortunately."

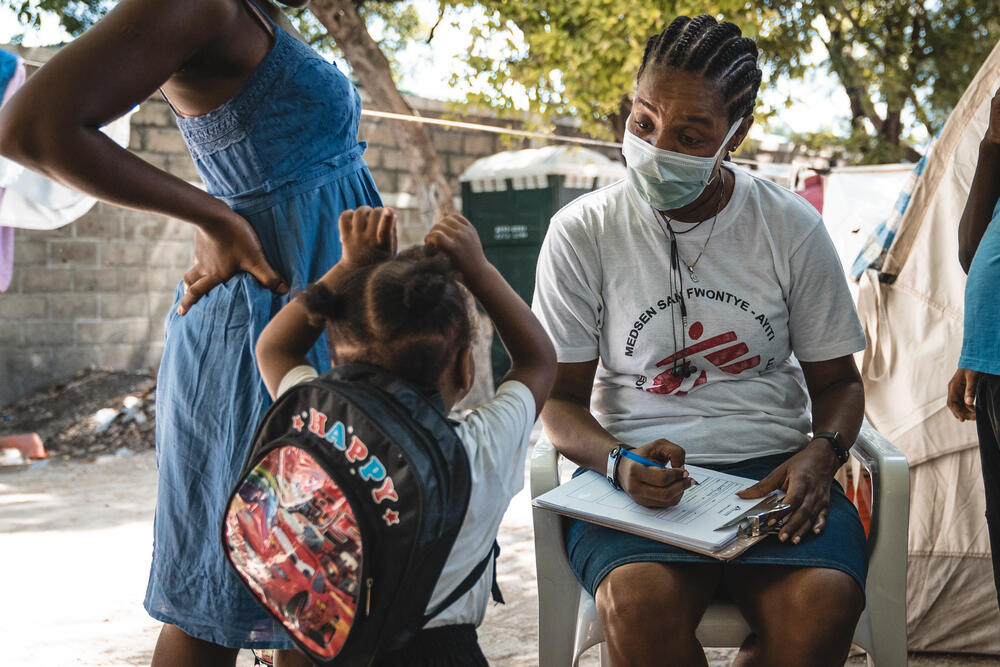

MSF in Haiti

At 8:30 am on 14 August 2021, a magnitude 7.2 earthquake struck the southern region of Haiti, specifically the provinces of Grande Anse, Nippes, and Sud. Within hours, Médecins Sans Frontières/Doctors Without Borders (MSF) teams were helping the wounded.

The death toll is now over 2,200, according to Haiti’s Office for Civil Protection, and more than 12,200 people were injured.

More than a decade after the Haiti catastrophic 2010 earthquake, the island nation’s health system is on the brink of collapse amid an escalating political and economic crisis.