Burkina Faso: Invisible scars from an unknown conflict

It was a Monday evening in July when armed men came to Fondioaga village in eastern Burkina Faso and killed a community member.

The next morning, they came back, murdering a second man, before continuing their killing spree in a neighbouring village.

“That was when we realised that if we stayed, they would kill everyone. So we fled with our wives, our children and our parents,” says 45-year-old O.K.*

He escaped with his family to the town of Matiaocoli, 25 km away.

“We left our belongings and animals behind and don´t know if they will still be there when we return home. Here, we have nothing at all. It is tiring. We are tired with worries.”

An escalating crisis

The world´s fastest-growing humanitarian crisis is unfolding in Burkina Faso. Over the past two years, escalating violence by armed groups in the north and east of the country has forced more than one million people to flee their homes.

Almost half of them have been displaced since the start of this year, following a surge in attacks.

Most people now live in precarious conditions, with limited access to water, food, proper shelter and healthcare, and in constant fear of renewed attacks.

During the current rainy season, displaced people and host communities face additional challenges, including surging rates of malaria and malnutrition. However, another health issue is less visible, but just as devastating.

A mental health emergency

“People who have witnessed a violent attack are often traumatised,” explains Médecins Sans Frontières / Doctors Without Borders (MSF) psychologist Issaka Dahila.

“First they ask themselves, ‘Why is this happening to me?’ Then they often feel guilty because they survived or they were not able to save others. Their suffering is even worse when they are forced to flee their homes.”

Faced with violence and displacement, people react and adapt in different ways. Some cope through family or community support. Others try to repress and contain their emotions.

"They ask themselves, ‘Why is this happening to me?’ Then they often feel guilty because they survived or they were not able to save others."

“We see people who come to us days, weeks or even months later with persistent complaints such as sadness, fear, denial or anger,” says Dahila.

“We sometimes hear them say, ‘I´m worthless! My life is meaningless’. Some people have difficulty seeing a future for themselves. Some even to want to end their lives. This summer, a young mother of a one-year-old boy committed suicide after men attacked her village and killed her husband.”

A person’s decision to end their life can be the result of significant psychological suffering that they can no longer sustain. From their perspective, the only way to stop this suffering, this perpetual pain, is to commit suicide or to try to commit suicide.

Although such cases do not occur often, they illustrate the trauma people affected by this violence are experiencing. In general, the number of patients with mental health concerns increases during conflicts – on average five percent of people develop severe mental disorders and 17 percent mild and moderate disorders.

The physical symptoms of trauma

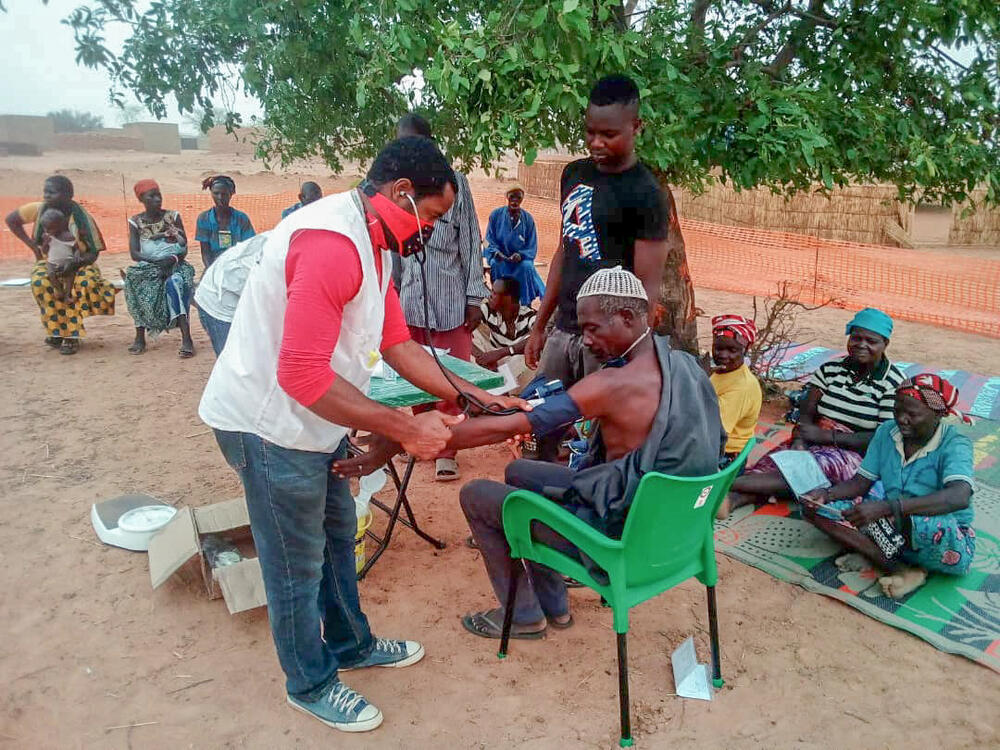

To help ease the suffering of displaced and host communities, MSF started mental health activities in Burkina Faso´s Eastern region at the end of 2019.

From July to September this year, 128 people attended individual consultations and 4,391 group mental health sessions. Some come to our clinics directly to seek help, many after being referred from other medical services.

“When we first meet with patients they describe physical symptoms, such a sleep problems, headaches, a stronger heartbeat, or feeling startled for no apparent reason. Generally, people are better at identifying physical problems than psychological and emotional ones,” says Dahila.

He says that children have their own way of reacting to the violence and displacement they have witnessed and experienced. Some show signs such as bed wetting and having nightmares, but others will be in denial. They may also use games to reproduce the traumatic event.

Psychological first aid

MSF’s Burkina Faso mental health team offers a number of services to alleviate the psychological suffering of people affected by violence, conflict or displacement.

922,500

OUTPATIENT CONSULTATIONS BY MSF IN BURKINA FASO IN 2024

118,085,000

LITRES OF WATER DISTRIBUTED BY MSF IN BURKINA FASO IN 2024

313,900

MALARIA CASES TREATED BY MSF IN BURKINA FASO IN 2024

These include individual, family and group counselling sessions, where mental health specialists focus on coping mechanisms and building resilience. Specific issues and diseases, such as sexual violence, HIV/AIDS and malnutrition, are also addressed.

For people who have recently experienced a traumatic event, MSF´s mental health specialists offer “psychological first aid”, a technique designed to reduce the onset of possible psychological trauma.

MSF is holding awareness sessions on the importance of mental health, but not everyone who needs it seeks help. One issue is the difficulty people face accessing mental health services in remote and insecure areas. Another challenge is the stigma that is still often associated with mental health issues in Burkina Faso.

*Name withheld to protect anonymity

MSF in Burkina Faso

MSF began work in Burkina Faso in 1995. At present, our teams are providing medical and humanitarian assistance to both displaced and host communities in East, Sahel, North and North-Centre regions.

This includes primary and secondary healthcare, vaccination campaigns, water, sanitation and hygiene, and ad hoc distributions of basic relief items.

In eastern Burkina Faso, MSF has been providing paediatric and maternal healthcare in two district hospitals and six health posts in Fada and Gayeri since 2019. We are also providing mental health services, running mass vaccination campaigns and have set up a network of community health workers trained to treat common illnesses and to detect and refer patients who require urgent medical attention.

We have also been working to improve access to water, initially through water trucking and later by drilling and repairing boreholes.