Fighting for treatment

A history of HIV care in South Africa

Twenty years ago, MSF was involved in a revolution in South Africa that would save thousands of lives and forever change the way the world saw and treated HIV.

MSF staff, alongside activists and people dying from AIDS, used mass protests and legal action, first against profiteering pharmaceutical companies and then against the South African government, to fight for free HIV treatment for all.

From clandestinely bringing medicines into the country to providing large-scale treatment, this is the story of a healthcare revolution.

A cruel irony

In 1994, as South Africa celebrated its hard-won freedom from apartheid, the country descended into a chilling new crisis. An incurable disease called HIV – which destroys the body’s immune system – was sweeping across the country.

“We were only seeing the sickest of the sick… people were brought in on stretchers or in wheelbarrows…”

By 2000, an estimated 4.2 million South Africans were infected by HIV. Nearly 1,000 people were dying a day. Stigma was powerful and dangerous.

Aside from the few who were privately insured, treatment was completely out of reach: a year’s worth of branded antiretrovirals (ARVs) cost £8,000 to £9,000.

Pharmaceutical companies refused to lower the price.

Promising scientific evidence from Thailand showed that a combination of ARVs, including azidothymidine or AZT, cut transmission from an HIV-infected mother to her foetus by 50 percent.

However, in South Africa, the health minister had blocked the use of AZT for pregnant women in the public health system.

In August 1999, MSF’s Dr Eric Goemaere arrived in Johannesburg to find a partner clinic for a “simple prevention of mother-to-child transmission (PMTC) programme” – only to learn that nothing about it would be simple.

Help us prepare for the next emergency

"We were only seeing the sickest of the sick"

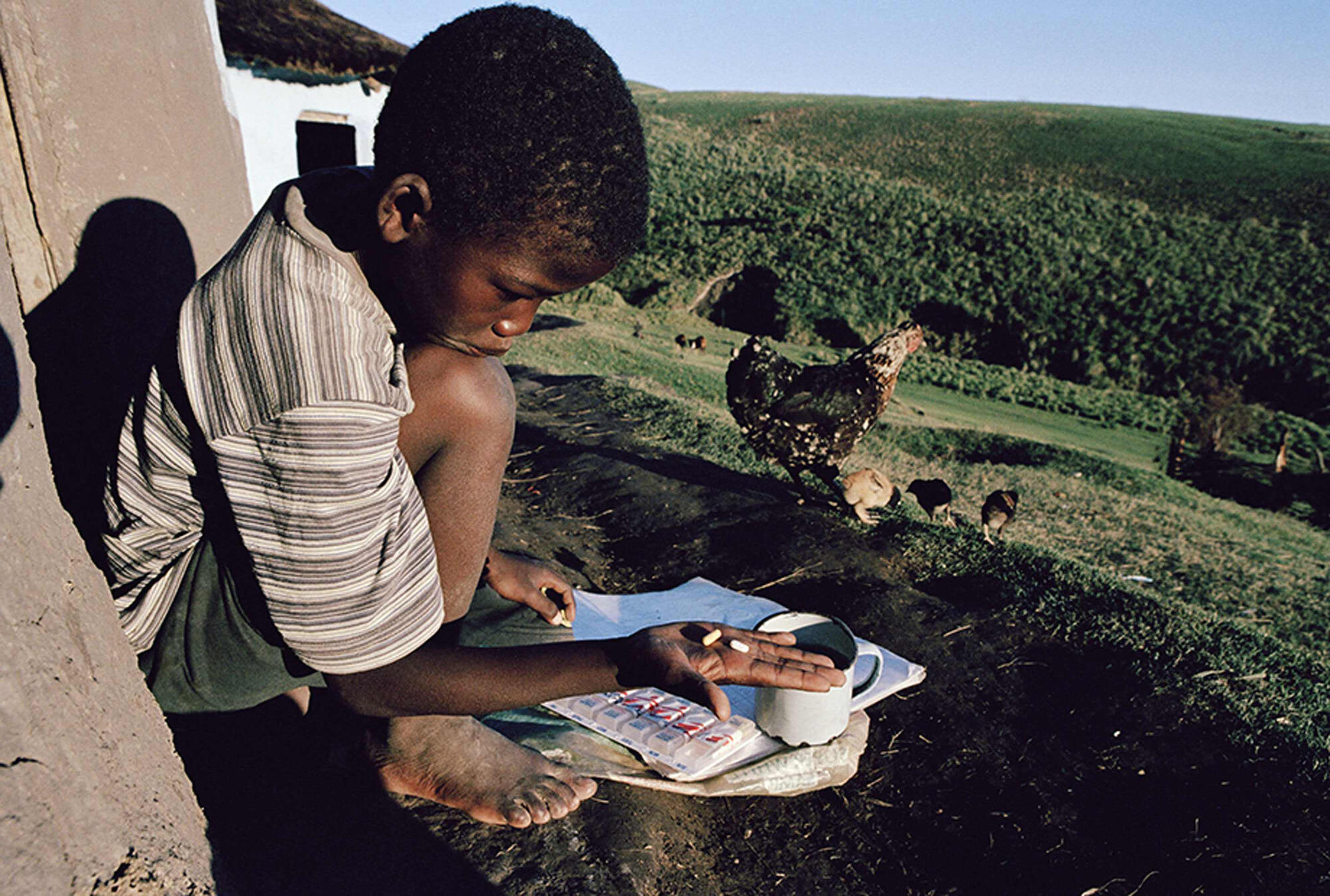

As late as 2001, prominent people maintained that ARV treatment in poorer countries was impossible: that year, Andrew Natsios, director of the United States Agency for International Development (USAID), told the US House of Representatives’ Committee on International Relations: “Rural Africans do not know what watches and clocks are. They use the sun.” Since they wouldn’t be able to take medicines properly, it was pointless trying to provide treatment.

The MSF team were anxious to prove to the scientific community that, contrary to accepted wisdom, ARVs could be safely administered to a poor African community, even outside a hospital setting.

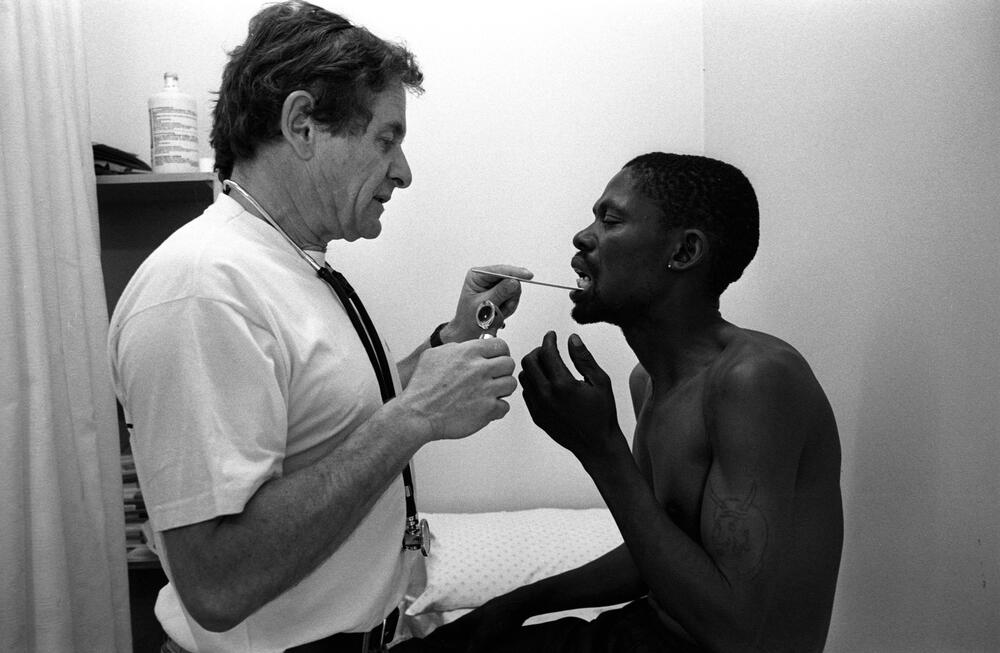

Against opposition, in February 2000, MSF and partners opened a clinic in Khayelitsha township, Cape Town, to treat infected mothers and their partners. The clinic was soon overflowing with patients.

“By the middle of 2000, a few months after we had opened, we had registered several hundred people as HIV-positive,” says Dr Goemaere.

“We were only seeing the sickest of the sick – those who were absolutely desperate. People were brought in on stretchers or in wheelbarrows. The waiting room was packed. Stigma dropped very rapidly because suddenly people realised – it’s not only me…”

A brief alliance

In 1998, a group of 42 pharmaceutical companies took the South African government to court when it tried to adapt its patent laws to allow it to import low-cost generic drugs, mostly antibiotics.

The case – Big Pharma vs Nelson Mandela – was stalled for three years until March 2001. A handful of HIV activists sprang into action to support the government, thinking this would open the gates for treatment for all South Africans.

On 19 April, faced with a public relations disaster, Big Pharma announced they were dropping the case. The crowd was jubilant.

“The court was filled with people and, while we were waiting for the judge, they started to sing,” says Ellen ’t Hoen, MSF’s legal adviser.

“Every hair on my body was standing on end. It was in the air that they were going to drop the case… When they did, the whole thing just broke out in one big dancing party. It was absolutely amazing.”

However, the government soon made it clear it was not interested in bringing generic ARVs into the country.

Despite being completely blocked by the Department of Health, MSF got local government approval for a full public ARV programme in Khayelitsha beginning in 2001 – the first in South Africa.

MSF just had to pay for the drugs. However, without generic ARVs this was financially impossible. At first, MSF could only put 180 people on branded ARVs.

Get closer to the Frontline

Get the latest news, stories and updates, straight to your inbox.

“This must be among the greatest-ever public health achievements in the history of humankind”

But thousands of people were ill. Clinic staff were forced to choose who would live and who would die.

Desperate for generic ARVs, MSF struck an undercover deal with the Brazilian government. MSF Brazil would buy generic ARVs from the Brazilian government and then ship them to their colleagues in South Africa.

However, MSF couldn’t wait for the generics to arrive. Goemaere’s clinic had been running for a year by this time and the situation was dire.

Buying over the counter

To buy enough drugs to keep patients on treatment, Goemaere visited one of the few pharmacies in Cape Town that supplied them.

The dozen treatments he purchased that day cost more than the second-hand Toyota he was driving. However, it was enough to tide them over until the first consignment of Brazilian ARVs arrived secretly via DHL in November. The first group of patients was switched to generic drugs.

In 2002, the MSF team presented results from the Khayelitsha project at the Barcelona AIDS Conference. The findings were explosive: 91 percent of patients were still on treatment and healthy.

The denialists could no longer ignore scientific fact. In early 2003, a landmark court case brought by the Treatment Action Campaign (TAC) found that two pharmaceutical companies had abused their dominant positions in the ARV market.

Four Indian companies that produced generic ARVs were finally allowed into South Africa.

On 8 August 2003, the South African government made the longed-for announcement that they were going to roll out free ARVs. The battle had been won.

A grassroots victory

“Looking back at these events, I am struck by how far HIV care has progressed,” says Dr Goemaere, who still works for MSF in South Africa.

“What sounded like medical utopia in early 2000 is now the norm rather than the exception in most sub-Saharan countries. Once we struggled to treat 400 patients and faced the terrible dilemma of selecting who would live and who would die.

“What a relief for clinicians now to initiate any new patient on ARVs, some at their first visit, without having to worry about limited resources.

“This must be among the greatest-ever public health achievements in the history of humankind. It was a struggle in which the best of science joined forces with the best of political will to change the course of the pandemic.

“It was a grassroots victory, with people fighting for their rights and for human dignity, first against pharmaceutical companies and then, unexpectedly, against their own government.”

Read the full story

The book, 'NO VALLEY WITHOUT SHADOWS, MSF and the fight for affordable ARVS in South Africa' can be downloaded for free.