Central African Republic: Patients left with few options after 36 attacks on MSF in 2017

"The first bullet hit a 13-year-old girl,” says Christelle. “I fell to the ground and they kept shooting. A bullet hit my ankle. Another bullet hit a child of two or three who was in a shelter next to the hospital wall. He died instantly.”

Christelle, 24, is still recovering after the surprise attack by armed men outside the hospital in Batangafo, in the north of Central African Republic (CAR), on 8 September 2017.

Many families saw their houses burned to the ground and their neighbours murdered.

Refugees in Congo

"I was trying to help the family hide from armed men who had entered the hospital when suddenly two of them found us,” says Debra, a Médecins Sans Frontières/Doctors Without Borders (MSF) staff member, who witnessed an attack on the hospital in Zemio, in the southeast of CAR, on 11 July.

Help us prepare for the next emergency

“They pointed their guns at us and shot the baby as her mother held her in her arms.”

One month later, Zemio hospital was again the scene of gunfire, when bullets were fired at 7,000 people who had taken shelter from the conflict there.

This was a turning point for the Zemio’s 22,000 residents. All those whom were able to flee the town crossing the border into neighbouring Democratic Republic of Congo (DRC), where they are now refugees.

Worst violence since 2013-14

"There were armed men shooting in the air around our ambulance while we were transferring a patient with acute diarrhoea to the hospital,” says Pelé, an MSF outreach nurse supervisor in Bangassou, southeast CAR.

“They were really on edge, making threats and not listening to anyone.”

Pelé was held by armed men for several hours with the rest of the MSF outreach team and one patient on 21 August.

The situation in Bangassou has deteriorated since May 2017, with most of the population fleeing to neighbouring DRC.

Approximately 2,000 Muslims have sought refuge in the compound of the Catholic church, where they are living with very little assistance from international aid organisations.

Christelle, Debra and Pelé are just three of the many thousands of people who, in the past year, have lived through the return of brutal violence to a country still trying to recover from the bloody civil war of 2013-14.

“In the past year, we have treated patients who have been shot, stabbed, beaten, burned in their homes and raped,” says Frédéric Lai Manantsoa, MSF country manager in CAR.

"In 2017 we witnessed levels of violence against the civilian population in CAR that evoked the worst months of the conflict of 2013-14.”

Christelle, Debra and Pelé are just three of the many thousands of people who, in the past year, have lived through the return of brutal violence to a country still trying to recover from the bloody civil war of 2013-14.

“In the past year, we have treated patients who have been shot, stabbed, beaten, burned in their homes and raped,” says Frédéric Lai Manantsoa, MSF country manager in CAR.

"In 2017 we witnessed levels of violence against the civilian population in CAR that evoked the worst months of the conflict of 2013-14.”

Almost 40 attacks on MSF in 2017

Not only have MSF teams in CAR heard horrific stories from their patients, they have also personally experienced violence in all of MSF’s projects in CAR over the past year.

In 2017, MSF suffered an average of three attacks per month against its medical facilities, vehicles and staff.

These attacks, and the numerous other incidents against civilians and aid organisations in other locations, made CAR one of the world’s most dangerous countries for humanitarian workers in 2017.

"After the attack on the hospital in Zemio, I was forced to flee to DRC with my family,” says Pierre Yakanza, MSF coordination assistant in Zemio until a few months ago, when he left the town to escape the violence along with most of his neighbours.

“I walked all night and crossed the river in a canoe. We couldn’t stay in Zemio – there is no administrative authority and anyone can do whatever they want.”

One in five people in this country of 4.5 million was forced to leave their home in 2017 because of the violence.

United National Refugee Agency (UNHCR) reported at the end of 2017 the highest number of displaced people inside CAR since the 2013 crisis: 688,000.

And more than 540,000 are now refugees in neighbouring countries.

Thousands left without medical care

MSF has treated people injured in this new wave of violence, as well as pregnant women or those with preventable or chronic diseases whose conditions have been aggravated by an inability to reach medical care on time owing to the conflict.

What marked the violence in CAR during 2017 was its effect on people’s access to medical care, especially when they needed it most.

This, combined with people’s reduced access to food, water, shelter and education, has brought the population to a state of extreme vulnerability.

Get closer to the Frontline

Get the latest news, stories and updates, straight to your inbox.

Previously, hospitals were one of the few places where people felt secure, with thousands of families taking shelter in hospital compounds for months at a time.

But they are no longer safe, as MSF teams witnessed during the course of 2017.

The past year has seen ambulances being brought to a standstill or attacked while transporting the wounded, indiscriminate shooting inside medical facilities, and patients being forcibly removed from their beds and executed in cold blood.

These have become everyday events in CAR, with disastrous consequences for patients.

The attacks of the past year demonstrate a complete disregard for humanitarian principles and jeopardise MSF's ability to protect both patients and staff.

In some places, such as Bangassou, violence and insecurity reached such levels that MSF was forced to make the difficult decision to suspend activities. In the case of Bangassou, patients were left without the assistance that could have saved their lives.

2018: renewed violence and no safe place to go

The outlook for the coming year is not encouraging.

"The health system is almost non-existent and the constant attacks against medical facilities, patients and ambulances make the situation even worse,” says Christian Katzer, MSF operational manager for CAR.

“Thousands of people have no access to medical assistance, and many will die from preventable diseases such as malaria, diarrhoea and respiratory infections, the three leading causes of death for children aged under five in the country.”

2018 began with another outbreak of violence, this time in Paoua and nearby Markounda, in the northwest of the country.

A dozen wounded were treated at Paoua hospital. They told of indiscriminate attacks, torched villages and large numbers of dead and injured people left behind in the bush.

The violence led to another 66,000 people becoming displaced within the country, while 20,000 people fled across the border to Chad in a bid to escape the bullets, rapes and lootings.

These attacks violate international humanitarian law, as well as national law in CAR. It seems that 2018 will offer no respite to a population who have no safe place to go.

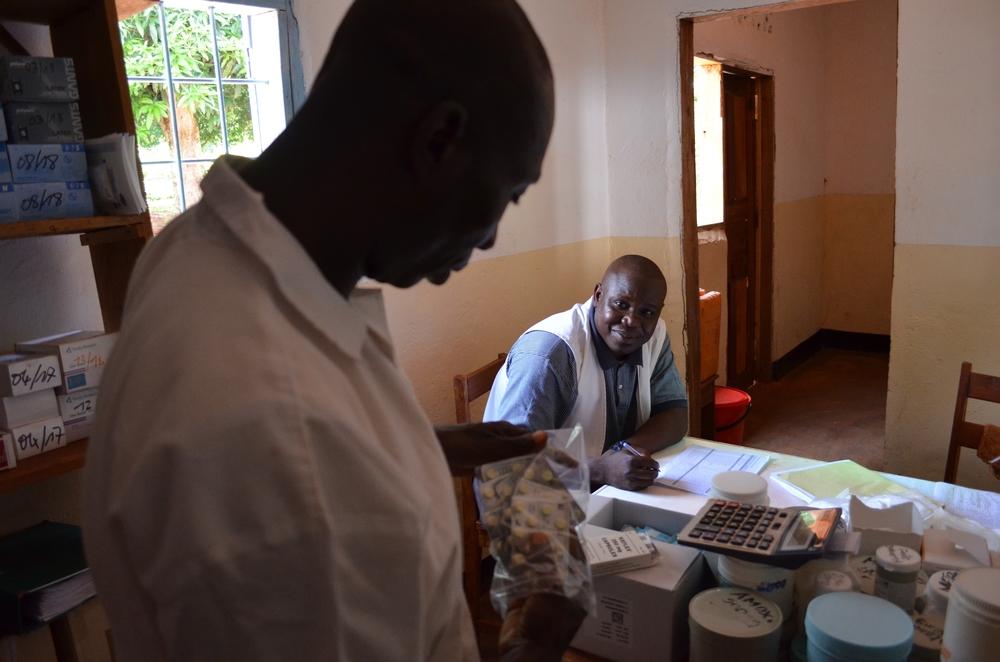

MSF's work in the Central African Republic

Since gaining independence in 1960, the Central African Republic has been plagued by political instability and violence.

It remains one of the poorest countries in the world, despite considerable natural resources. Despite a peace deal signed in February 2019, extreme violence has continued in many regions of the country, exacerbating the already immense humanitarian needs.

Médecins Sans Frontières/Doctors Without Borders (MSF) first began work in Central African Republic in 1997. Our teams run projects for local and displaced communities in eight provinces and in the capital, Bangui, providing primary and emergency care, maternal and paediatric services, trauma surgery and treatment for malaria, HIV and tuberculosis.